Shrinking demographics and weak productivity growth have combined to paint a dismal picture of Canada’s economic future. As the Bank of Canada’s Senior Deputy Governor Carolyn Rogers explains, Canada’s central problem is a lack of long-term investment. In fact, the nation’s productivity woes are largely about weaknesses in strategic planning. This dismal picture includes missed opportunities in electric vehicles (EVs), high-speed rail, 5G (fifth-generation) telecommunications, and now a new wave of commercial robotics. Indeed, the rapid convergence of artificial intelligence (AI) and robotics represents an enormous opportunity to catalyze the Canadian economy.

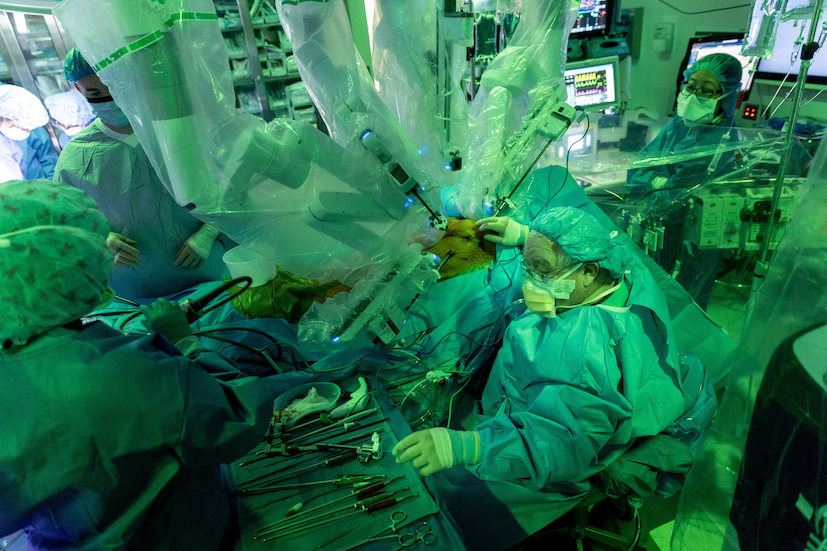

There are some four million robots installed in factories around the world. Robots are now deployed across a range of industries, including manufacturing, construction, mining, logistics, health care and the military. On a wage-adjusted basis, Asian nations lead the world in robot adoption. While Western companies still have the most advanced software models, Asia has become the centre of manufacturing because of its dense supply chains, lower manufacturing costs and government-led planning.

Given the economic challenges now facing Western economies, one might assume that robotics would be top of mind for rejuvenating manufacturing in the United States and Canada. Unfortunately, business leaders in North America have begun ramping down investments because of sagging demand. This is ironic, given the fact that Western economies have the highest labour costs in the world. Indeed, even as China remains the world’s factory, Chinese manufacturing now deploys 12 times the rate of robots used in the United States.

Competing with China

While the United States invented robotics, Germany and Japan now lead the industry. However, it is China that is the world’s largest market. With more than half the world’s stock of operational robots, China surpassed

one million units in 2021 and 1.5 million units in 2022. In fact, some 73 percent of installed robots are in Asia, while only 15 percent of the world’s robots are installed in Europe and 10 percent in North and South America.

China’s strategy in robotics mirrors its approach to dominating everything from telecommunications and renewables to EVs and industrial equipment. China is a fast follower with immense scaling capacity. Using long-term industrial policy to dominate supply chains, Chinese planners use financial incentives to push their entrepreneurs to climb the global value chain. By comparison, nearly all robots in Canada are imported from abroad. With the exception of the automotive industry, Canada’s adoption of robotics is among the lowest among the Group of Twenty economies. This must change.

Canadian planners need to think strategically about the future of the Canadian economy. Catching the current wave of robotics investment could streamline Canada’s slow-moving sectors and enable Canadian workers to focus on strategic innovation. By integrating AI and robotics into large sectors such as manufacturing, health care and agriculture, Canada could not only substantially expand its economic output and accelerate its productivity but also improve the quality of its labour force.

It’s Time to Build Again

Contemporary robotics can be divided into four major classes on the basis of their design and function:

- pre-programmed robots: robots that operate in controlled settings, such as the robotic arms now commonplace in manufacturing;

- autonomous robots: robots that operate independently using sensors to make decisions, such as drones or robotic vacuums;

- humanoid robots: robots that mimic human behaviour and appearance in order to match human expertise; and

- tele-operated robots: typically, robots operated in hazardous environments, such as mining or military operations.

Building out the tech platforms needed for advanced manufacturing involves three critical policy ideas. First, Canada needs a manufacturing strategy that leverages disruptive technologies. Whether we aim to produce solar panels or semiconductors or military equipment, Canadian firms will need to augment their labour force with AI and robotics. Doing so means incentivizing domestic industries to “buy Canadian.” By procuring AI and robotics from local companies, Canadian firms can help catalyze the tech sector while improving productivity for the economy as a whole.

Second, Canada needs a national strategy for financing innovation. Like so many other countries that understand the relationship between risk and reward, Canada needs growth-themed investment funds dedicated to AI and robotics. These financial tools are commonplace in countries such as China, Denmark and South Korea, where strong robotics ecosystems have begun to flourish. Without generous public-private investment funds, none of these countries would enjoy the kind of success they now experience in advanced technology.

Last, Canada needs a coordinated strategy for expanding and consolidating our deep tech ecosystem. The federal government should convene a robotics industry advisory group to advise on industry needs in order to build out Canada’s robotics industry. These needs would include expanding funding for robotics research and, in particular, research that overlaps industrial manufacturing. Current funding programs are simply too narrow and lack the scale to match the speed and scope of growth needed to compete internationally.

The challenges now facing the Canadian economy are significant and real. The hard reality is that Canadians need to get serious about long-term strategy. Notwithstanding the enormous affluence inherited from previous generations, our economic future faces significant headwinds. If we fail to prioritize the tools and technologies needed to support Canadian businesses as they move up the global value chain, we risk being sidelined by Asia’s growing leadership in advanced manufacturing.