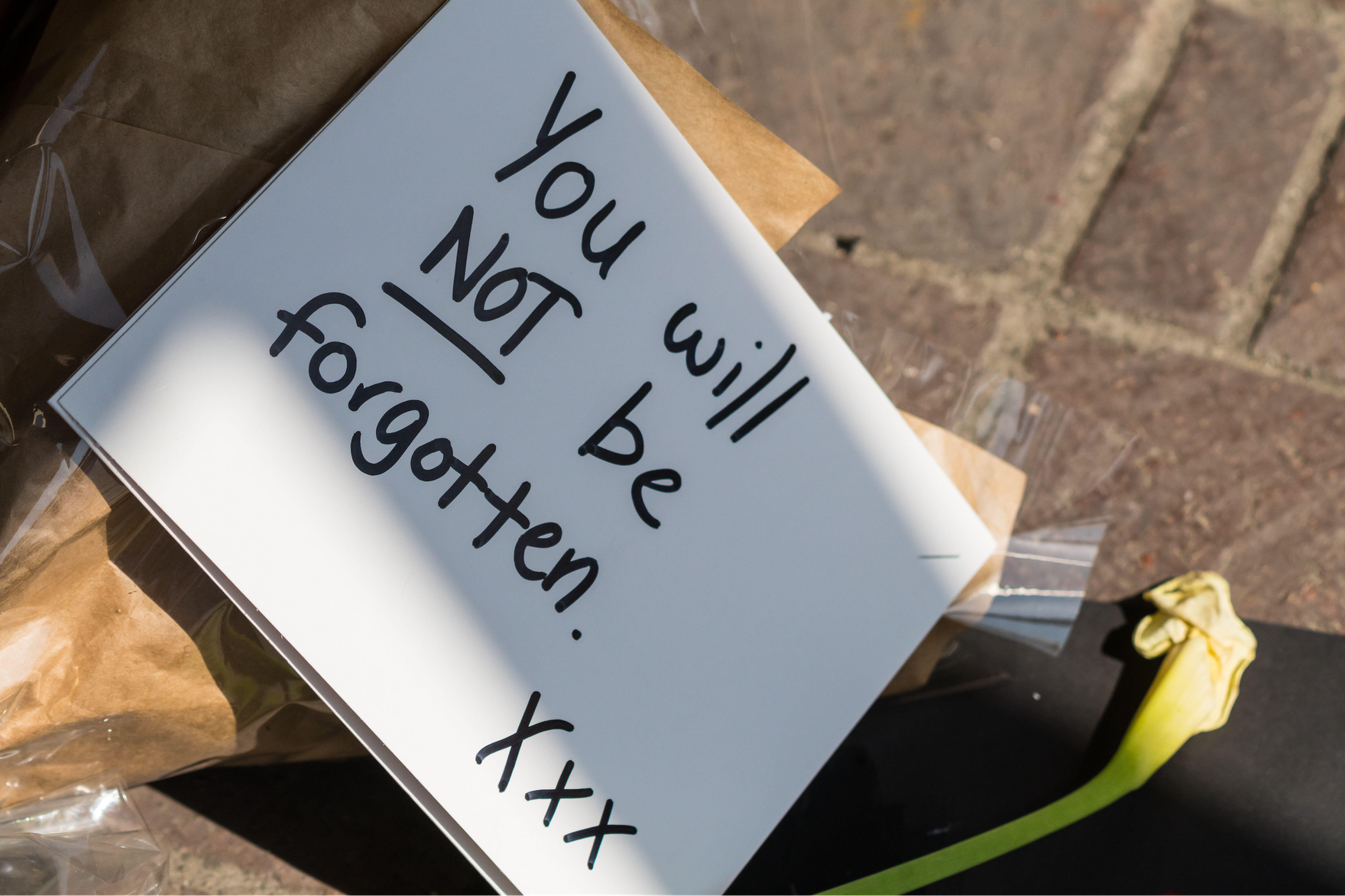

On October 14, 2022, 10 years almost to the day after 15-year-old Amanda Todd committed suicide following years of sextortion, bullying and mental anguish, a Dutch-Turkish dual citizen, Aydin Coban, was sentenced to 13 years in prison, a year more than requested by the prosecution. Already serving time in the Netherlands for similar crimes, Coban was ordered to serve the two terms of imprisonment consecutively. In imposing this sentence, BC Supreme Court Justice Martha Devlin said that the defendant’s conduct called for a “sharp rebuke.” Barring any appeals, this brings to a close a case that has captured Canada’s — and the world’s — attention since Amanda Todd posted a heart-wrenching video online weeks before her suicide in 2012. The video consisted of Amanda holding up a series of flash cards telling her story. According to Daily Beast reporter Nadette De Visser, by 2017, the video had been viewed “more than 20 million times.”

The International Dimension of the Amanda Todd Case

In 2014, two years after Amanda Todd ended her life, Coban was arrested in the Netherlands and charged with, among other crimes, indecent assault, the production and dissemination of child pornography, fraud, and computer intrusion involving dozens of young women and girls and several gay men. At the same time, in Amanda Todd’s case, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) charged Coban with extortion, communication with a young person to commit a sexual offence (internet luring), criminal harassment and two counts of possession and distribution of child pornography. In the Netherlands, the child pornography charges were later dropped. In 2017, Coban was tried and convicted for internet fraud and blackmail and sentenced to 10 years and eight months in prison, the maximum allowable under Dutch law.

In December 2020, Coban was extradited to Canada to face charges in the Todd case, which had been separated from the Dutch prosecution. His trial in New Westminster, British Columbia, began in June of this year and lasted nearly two months. On August 6, a jury found Coban guilty on all five counts.

The Push and Pull of Social Media

The CBC reported that Carol Todd, Amanda’s mother and the first witness to testify at the New Westminster trial, told the BC court that “her daughter loved to sing and learned at an early age how to take videos of herself and post them online,” and that Todd said, “It was a time when Justin Bieber became famous online and Amanda like many other people wanted to become famous — just like Justin Bieber.” In their testimony, both Amanda’s mother and her father, Norm Todd, the second witness to testify, “spoke of her [Amanda’s] anguish and panic at receiving the threats and said that while RCMP had advised Amanda Todd to get off Facebook, that was easier said than done for a child who thrived on social media interaction.”

Writing in The Atlantic, Jonathan Haidt, a social psychologist at the New York University Stern School of Business, states that “from 2010 to 2014, high-school students moved much more of their lives onto social-media platforms. Notably, girls became much heavier users of the new visually oriented platforms.” He points out that “the move onto social-media platforms … made it easier — indeed, almost obligatory — for users to perform for one another.” The result has been devastating, especially for teenage girls, as described by Haidt: “The wrong photo can lead to school-wide or even national infamy, cyberbullying from strangers, and a permanent scarlet letter.” This is what happened to Amanda Todd, as described in testimony by Carol Todd at Coban’s Dutch trial in 2017. Carol Todd told the court that her daughter had been bullied relentlessly after her photo was posted: “They called her names … people were brutal, they wouldn’t let her forget.”

According to Haidt, “performative social media also puts girls into a trap: Those who choose not to play the game are cut off from their classmates. Instagram and, more recently, TikTok have become wired into the way teens interact, much as the telephone became essential to past generations.” There is a further trap, or double bind, as well. Katie J.M. Baker, reporter for the website jezebel.com, speaks of “a culture that sends young women … mixed messages by teaching them that the only way they’ll be loved is if they show off their bodies, unless they do it too often/the wrong way/to the wrong people, in which case, they’re sluts.” This explains in part why Amanda Todd was bullied by her classmates when Coban sent her photo to her schoolmates.

Legal scholar and writer Benjamin Wittes and colleagues Cody Poplin, Quinta Jurecic and Clara Spera, writing for the Brookings Institution, argue that young internet users are soft targets for cybersecurity threats such as sextortion: “Teenagers and young adults don’t use strong passwords or two-step verification, as a general rule. They often ‘sext’ one another. They sometimes record pornographic or semi-pornographic images or videos of themselves. And they share material with other teenagers whose cyberdefense practices are even laxer than their own. Sextortion thus turns out to be quite easy to accomplish in a target-rich environment that often does not require more than malicious guile.” At Coban’s sentencing hearing in New Westminster, BC Supreme Court Justice Devlin addressed this issue directly in her concluding remarks, warning young people about the dangers of using the internet and how easy it is for adults to disguise their true identities when interacting with children online.

The case of sextortionist Aydin Coban raises many important questions about online harassment, cyberbullying and the wider societal response to online victims. Chief among these questions is the role of anonymity in facilitating such crimes.

The Dark Side of Anonymity

The case of sextortionist Aydin Coban raises many important questions about online harassment, cyberbullying and the wider societal response to online victims. Chief among these is the role of anonymity in facilitating such crimes and hindering their investigation and prosecution. According to jezebel.com reporter Katie J.M. Baker, Coban “created a Facebook page with a list of her [Todd’s] friends and school, using Amanda’s naked chest as his profile photo.” How did Coban obtain this photo? By chatting her up online anonymously and flattering her about her looks — in Amanda’s words on the fifth flash card in her YouTube video: “stunning, beautiful, perfect.” As reported by the CBC, BC Crown prosecutor Louise Kenworthy told the jury on the first day of the trial that Coban used different user accounts “to pose as teenaged boys and would-be friends in order to elicit more material that he could use for sextortion.”

Amanda Todd became for Aydin Coban what Mary Anne Franks calls an “unwilling avatar,” a virtual self-representation hijacked from the original source for nefarious purposes. In Frank’s words, “the creation of unwilling avatars involves invoking individuals’ real bodies for the purposes of threatening, defaming, or sexualizing them without consent.”

The chief defence that Coban’s lawyers relied on, in both the Netherlands and Canada, was that the prosecution could not prove that their client was behind the threatening messages sent to Amanda Todd or the dozens of other girls and several adult men. While Amanda Todd, some of her friends, and her school all notified police about the threats against her, according to Crown prosecutors at the New Westminster trial, “police were unable to identify a suspect when they investigated Amanda Todd’s complaints in 2010 and 2011.” Coban exhibited technological sophistication, masking his Internet Protocol (IP) address so the RCMP could not identify suspects. He also used anti-forensic software, disguising his voice and hacking into password-protected routers to steal Wi-Fi connections.

In 2012, a Norwegian girl notified police that she was being extorted online and they tracked the attacker’s IP addresses to the Netherlands. The information was passed to the Dutch police, who traced the addresses to a trailer park where Coban lived. The investigation stopped there. Only after Amanda Todd died and her video went viral did the Dutch police resume their investigation. According to the Daily Beast’s Nadette De Visser, a Facebook report on the Todd case linked a phone number with an IP address and numerous accounts used to target young girls. This led police to Coban’s home, where they were able to plant spyware on his computers.

After Coban was arrested in the Netherlands, his lawyer claimed that the evidence against his client was weak: “If I see the evidence, it’s not much. Lots of references to IP addresses and such,” and suggested that any evidence of illegal activity linked to his client could have been hacked. In a statement to reporters outside the New Westminster courthouse, Coban’s BC lawyer stated: “There’s no doubt that Amanda Todd was the victim of a lot of crimes. This case is about who was behind that.” Clearly, the heart of the prosecution’s case in both countries was to show that it was Coban who used the social media accounts to target and extort his victims. The RCMP identified 22 fake social media accounts that were used to threaten the BC teen. The challenge was to link these accounts with a real person. Despite the expressed confidence of Coban’s lawyers, the spyware planted on his computers enabled police to collect every keystroke and numerous screenshots in real time. It was this forensic evidence that convinced juries in both the Netherlands and Canada to find Coban guilty.

Internet-Based Crimes Can Be Successfully Prosecuted

Internet crimes transcend national borders. Aydin Coban’s victims lived in many different countries, including Britain, Canada, Norway and the United States. After sentencing, the BC Prosecution Service thanked judicial authorities and police in British Columbia, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, the United States and Australia for their cooperation. The police investigation necessitated technical knowledge, such as the use of spyware, keyloggers and screen capture. Dutch police had the requisite skills to conduct such an investigation once they were able to obtain a warrant to enter Coban’s home. Facebook’s own investigation was very likely instrumental in helping the Dutch police obtain such a warrant. In both the Dutch trial and the Canadian trial, Dutch police investigators were primary prosecution witnesses, presenting their evidence from their forensic investigation of Coban’s computers. In Canada, the defence did not even bring any witnesses, no doubt because the forensic evidence was so strong. The CBC reported that BC Crown Prosecutor Louise Kenworthy noted that “forensic examination of the computer equipment showed that while a lot of information had been deleted, files linking Coban to the phony usernames and accounts still remained, as did traces of videos that had contained the name Amanda Todd.”

One reason that Coban was successfully prosecuted is because most of his victims were underage. Amanda was 12 years old when he started harassing her. That is why child pornography laws were invoked in both countries, although Dutch prosecutors ultimately relied on laws related to internet fraud and blackmail. Police often tell victims that online harassment and bullying are civil matters, yet there are clearly many criminal offences that can be used to prosecute such activities. Until tech-facilitated gender-based violence is understood for what it is by law enforcement, prosecutors, judges, tech platforms and society at large, the fight against those who engage in these activities will always be an uphill struggle.

The Amanda Todd case shows that increased forensic skills on the part of police, willingness to prosecute and pursue a case to its conclusion, cooperation across national borders and between public and private sectors, and involvement of families and friends of victims in the investigation and prosecution can all improve the likelihood of a successful conviction.