The International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID) is playing a key role in making women a greater part of the international investment dispute settlement system. The ICSID is taking numerous and concrete steps to address the gender imbalance in the field and is making itself accountable by publishing those results. This is part of a larger global trend to make international legal systems and international commerce more inclusive of women.

Achieving economic empowerment of women through their inclusion in local, national and international commerce remains a fundamental challenge for the global trade and investment system overall. The World Trade Organization’s (WTO's) recently signed Declaration on Trade and Women’s Economic Empowerment is an innovative step toward this goal, as are the inclusion of “gender chapters” in the Canada-Chile and the Chile-Uruguay free trade agreements (FTAs).

In addition to progressive FTAs and the WTO declaration, the World Bank has also prioritized gender equality in its international development work. The World Bank’s gender strategy for 2016–2023 focuses on four priorities:

- improving health, education and social protection;

- removing constraints on women’s participation in the labour force;

- removing barriers to women’s ownership and control over assets; and

- enhancing women’s voice.

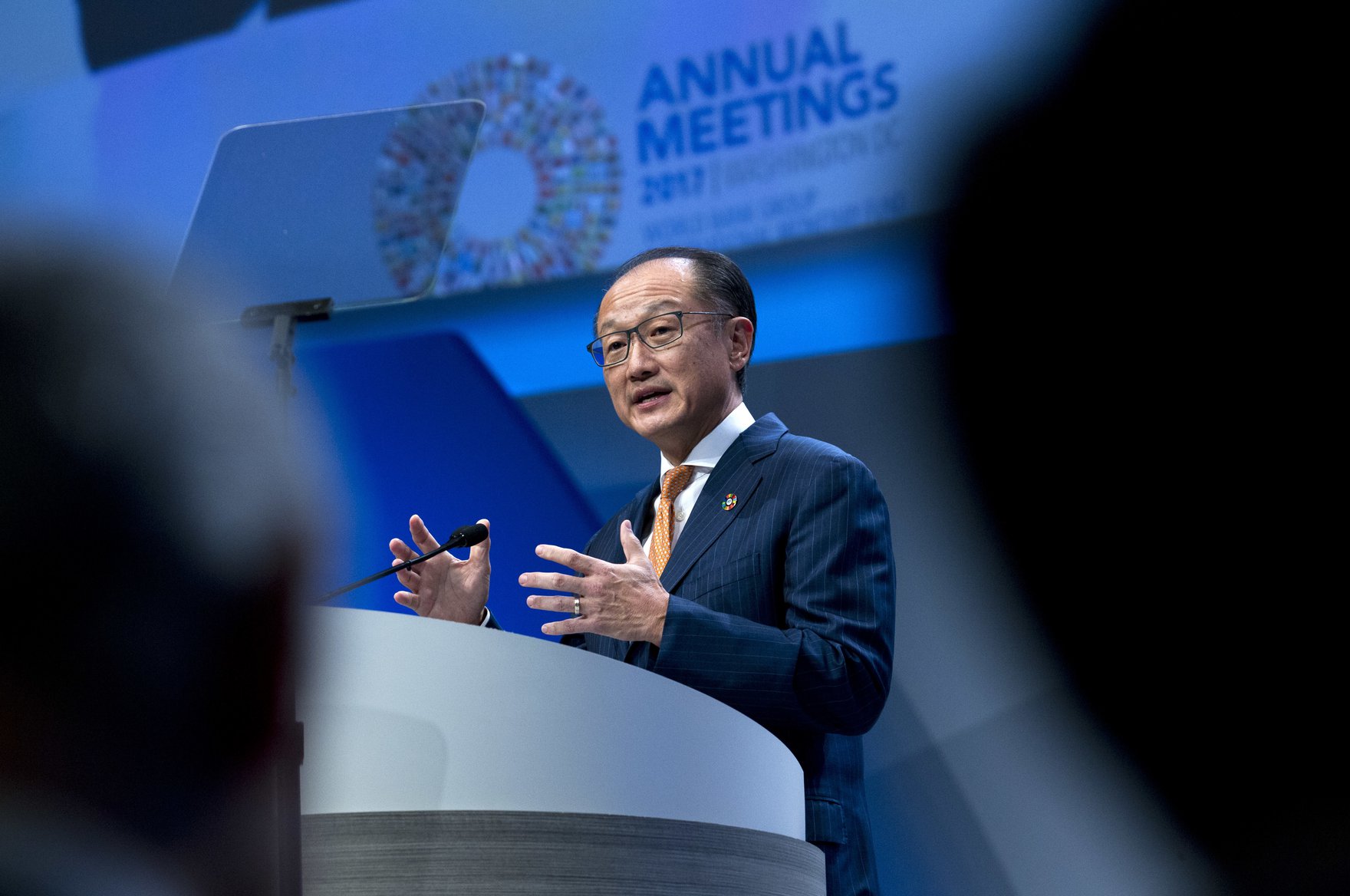

Far-reaching benefits are behind this strategy, says World Bank President Jim Yong Kim: “When countries value girls and women as much as boys and men; when they invest in their health, education, and skills training; when they give women greater opportunities to participate in the economy, manage incomes, own and run businesses — the benefits extend far beyond individual girls and women to their children and families, to their communities, to societies and economies at large.”

But there’s still work to be done to involve women in all facets of international trade and investment dispute resolution. Women remain significantly underrepresented in these fields, both as counsel and especially as lead counsel or “first chair,” and as judges and adjudicators. As Professor Nienke Grossman of the University of Baltimore School of Law has noted in her leading article, “Shattering the Glass Ceiling in International Adjudication,” “since 1998, an average of 13% of judges on international courts without representativeness requirements have been women, while, on average, 31% of judges on courts with such mandates or aspirations were women,” and looking again at the empirical data in 2015, “on most international courts and tribunals,…men continue greatly to outnumber women on the bench.” However, the tides are beginning to turn because of various international efforts.

A particular initiative was recently advanced in the international arbitration world. In response to the absence of women acting as counsel or as arbitrators, a diverse international group of lawyers, arbitrators, academics, states, arbitral institutions and law firms joined together in 2015 to take “the pledge” for equal representation in arbitration. The pledge consists of an undertaking by its signatories to improve the profile and representation of women in arbitration and appoint women as arbitrators on an equal-opportunity basis. Concrete steps suggested for those taking the pledge include nomination of a fair representation of women on lists of arbitrators and rosters of standing candidates, appointment of a fair representation of women for arbitrations, making gender statistics on appointments publicly available and mentoring women in the field.

The ICSID has also taken steps to increase the representation of women from all parts of the globe in international investment arbitration and conciliation cases. As the world’s leading institution in investor-state dispute settlement (ISDS), the ICSID has a significant role in supporting gender equality in the field. The ICSID possesses unparalleled expertise, gained through hundreds of investment arbitration proceedings, including management of procedural milestones, such as the appointment of arbitrators and the constitution of tribunals, conciliation and annulment committees. The ICSID also has a roster of arbitrators and conciliators compiled by its 153 member states, giving a unique vantage point on the participation of women in ISDS globally.

Reflecting the Reality

The ICSID contributes to the advancement of women in ISDS in several different ways.

First, the ICSID Secretariat collects and regularly presents data on the appointment of women as arbitrators in ICSID proceedings. The ICSID’s data on the participation of women in international arbitration shows that there is still a relative shortage of female arbitrators in ISDS. For instance, between the creation of the ICSID in October 1966 and December 2017, more than 2,200 appointments were made to ICSID tribunals and ad hoc committees, yet only nine percent of appointees over that period were women.

While this is a disappointing number, the situation is improving. Of the 195 appointments made to ICSID tribunals or ad hoc committees in 2017, 19 percent were women. That is already a significant improvement from 2016, when only 13 percent of appointees were female. The improved gender numbers also contributed to an improvement in the overall diversity of appointees. Of the 37 appointments of women in 2017, there were 18 different individuals named and they were nationals of a dozen different states.

In most cases, the instrument of consent to arbitration mandates party appointment, with appointment by an institution generally as a default measure in the absence of a party making its appointment. As a result, disputing parties appoint roughly 75 percent of all ICSID arbitrators. As presented in the ICSID’s annual report, in the 2017 fiscal year, 14 percent of all appointments involved women. The ICSID and the respondent/state each appointed 43.5 percent of these female appointees, while the parties jointly appointed 13 percent of female arbitrators. No women were appointed by the claimant individually or by the co-arbitrators. In 2017, the ICSID made a total of 58 appointments, of which 24 percent were women and 76 percent were men. Given the prevalence of party appointment in ISDS, parties, their counsel and party-appointed arbitrators will clearly play a key role in advancing the participation of female arbitrators in ISDS.

Adopting Best Practices

Second, the ICSID incorporates gender awareness in its best practices for appointing individuals to ICSID tribunals, conciliation commissions and ad hoc committees. For example, when called upon to appoint an arbitrator, the ICSID always includes at least one woman among the candidates it proposes in a list or ballot compiled for the parties, and this has increased the number of women ultimately appointed to tribunals and committees. Similarly, the ICSID has encouraged its member states to consider diversity when making designations to the panels of arbitrators and of conciliators, as mentioned in its recent note on “Considerations for States in Designating Arbitrators and Conciliators to the ICSID Panels.” In September 2017, the chairman of the ICSID’s administrative council made 10 new designations to each of the panels of arbitrators and of conciliators, and designated an equal number of men and women on each of the panels for the first time in the ICSID’s history.

Third, the ICSID provides women in the ISDS field with an opportunity to showcase their expertise at conferences and through its publication of the ICSID Review – Foreign Investment Law Journal. The ICSID Review publishes case comments, notes and articles on contemporary issues in international investment law and ISDS in Spanish, English and French. This kind of opportunity is particularly important in international dispute settlement, where parties making appointments may not always be aware of the breadth of expertise available in different regions.

Leading by Example

Finally, the ICSID reflects its commitment to the increasing participation of women in international investment arbitration in the composition of its own Secretariat, with women comprising more than 74 percent of its staff. Women fill all types of positions, including legal assistants, paralegals, counsel, financial officers, Deputy Secretary-General and Secretary-General.

There is no doubt that there is a significant distance to go in achieving greater representation of women in international arbitration. However, there is much to be optimistic about. We are seeing concrete changes, not just from a statistical perspective but also in the willingness of parties, their counsel and institutions to consider female arbitrators. As more women join the profession and gain seniority in arbitration, they will certainly become more prominent as counsel and as arbitrators, and equal representation of women in international arbitration will be commonplace rather than aspirational.