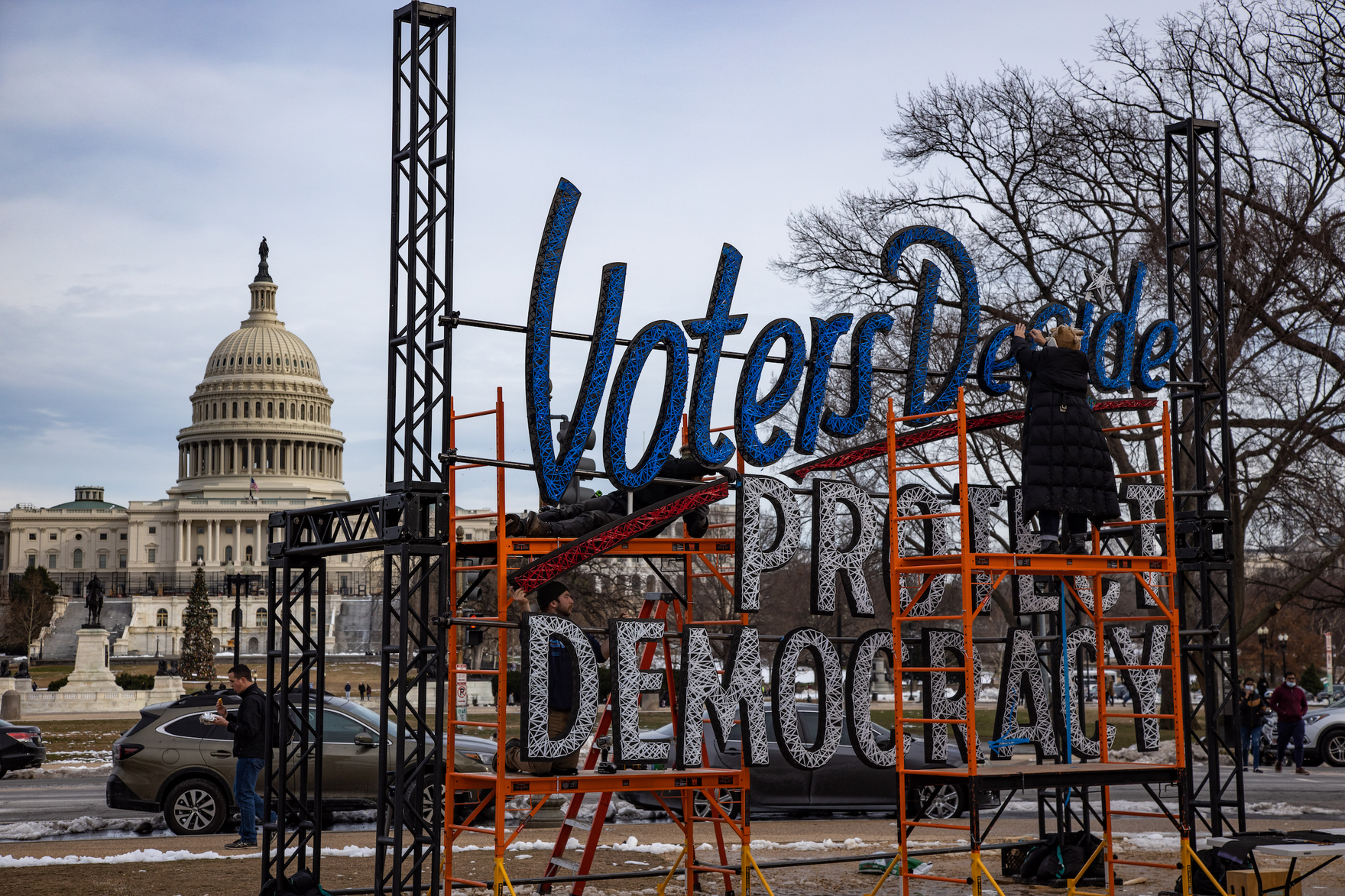

While millions have been captivated by the dramatic testimony delivered during the US House Select Committee’s hearings into the January 6 Capitol riots, Western officials are looking ahead to how threats to democratic processes, particularly elections, may unfold in advance of the 2022 mid-terms.

In particular, officials from the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) have issued warnings that Russia is seeking to exploit real or perceived election irregularities to sow doubts about the legitimacy of democratic systems. According to media reports, such efforts may include small-scale hacks of local election authorities, designed to draw notice, and then the exploitation of the discovery of those cyber intrusions to raise doubts about the legitimacy of election results. Such tactics will complement and amplify conspiracy theories, promoted by former president Donald Trump and his followers, that “the system is rigged” and unfair.

For Russia to engage in these tactics would represent another evolution in its overall strategy to undermine confidence in Western democratic systems — a strategy that has come a long way since 2016. At that time, Russia sent human sources to gather information about the US political system, to find ways to support Trump’s presidential campaign using social media. This activity was bolstered through a “hack and dump” effort, where Russian-backed actors broke into the accounts of Democratic Party officials in order to “leak” their data in ways that amplified conspiracies around the party and Hillary Clinton.

These “malinformation” campaigns (whereby, according to the Canadian Centre for Cyber Security, malicious actors use “information that stems from the truth but is often exaggerated in a way that misleads and causes potential harm”) have evolved. In 2017, Russian-backed hackers obtained access to 9 gigabytes of then presidential candidate Emanuel Macron’s documents and published them on the internet. However, this time the hackers were more ambitious in their approach, seeking to plant fake information within the stolen messages. That “information” included fraudulent claims that Macron held offshore accounts in the Cayman Islands to evade tax.

Other countries have also raised concerns that Russia (and other authoritarian states) no longer seek to sway elections for particular candidates but are instead engaged in a long-term strategy of discrediting democratic institutions. By doing so, they likely aim to increase dysfunction and division within Western countries and lessen the appeal of democracy worldwide.

However, the recent DHS warning is so far the most specific, and may reflect an effort to “prebunk” the threat — that is, to call out malicious behaviour before it occurs to disrupt it or mitigate its impact. In addition, it’s important not to overplay the “Russian bot” narrative. Humans have agency and are more likely to be swayed by domestic actors and influencers than by anonymous social media accounts.

However, online disinformation networks have developed over the last decade, many fed by Russian-amplified antisemitic, anti-LGBTQ+, anti-immigrant and anti-globalist conspiracy theories. As a growing far-right media ecosystem and political actors have adopted these narratives, they have become more potent. Given Trump’s continuing loud championing of the idea that the 2020 election was stolen, we can expect domestic actors in Western countries to adopt these narratives should a Russian hack (deliberately or not) be discovered.

Accordingly, election officials will have to be prepared to be as transparent as possible with the public and to issue warnings in advance of and possibly during elections. Governments need to do their best to secure election systems and the networks behind them to try to prevent hacks in the first place. Social media companies, many of which have a very mixed track record in dealing with misinformation, disinformation and malinformation on their platforms, will need to look for coordinated inauthentic activity promoting false narratives.

Finally, and most concerning, governments will need to prepare for increasing attacks, some violent, on democratic and other societal institutions. In recent weeks there has been media reporting documenting the abuse of election workers in the United States who are seen as part of a great conspiracy to steal elections. A Reuters investigation, for example, found more than 100 examples of threats of death or violence to election workers by Trump supporters, resulting in only four arrests. While this abuse is disturbing on its face, it has a wider impact: these threats may make it hard to recruit the election volunteers and front-line workers on whom Western democratic systems rely.

Moreover, when election results are disputed, individuals who are convinced their votes have been stolen may attack the very institutions that play a role in solving disputes and settling matters. Already there have been numerous threats against judges involved in hearings of individuals accused of participating in the January 6 attack on Capitol Hill. Similarly, in Canada, judges presiding over trials involving so-called “freedom convoy” supporters have received threats to their physical safety.

The existence of networks of individuals primed to receive and believe conspiracy-driven narratives, and of adversarial states willing to exploit them for their own ends, presents a real challenge for Western countries. As Russia seeks to distract North Atlantic Treaty Organization democracies from their efforts in Ukraine, we can expect further efforts to amplify and encourage domestic extremists who seek to remedy their grievances through the threat of violence.

This piece first appeared in Newsweek.