Before the Biden administration imposed restrictive export controls on advanced chips in 2022–2023, Chinese companies had been able to purchase or manufacture overseas high-end chips for data centre and cloud computing, artificial intelligence (AI) model training and other uses. Huawei’s powerful Ascend 910 chip series, released in 2019, was fabricated by Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC) using the cutting-edge “7 nm process node” system.

To explain: the 7 nm (nanometre) process node represents the benchmark in mature manufacturing procedures of advanced chips. These chips are extremely sophisticated and generally require the most advanced fabrication equipment, such as ASML’s extreme ultraviolet (EUV) lithography machine for mass production. Advanced chips for cloud computing and mobile phones can be mass-produced using the 7 nm process. TSMC began using the 7 nm process node to produce chips for the iPhone XS in 2018.

In the semiconductor industry, in particular in the field of chip manufacturing, China has generally lagged two or three generations behind global leaders such as Taiwan and South Korea. China had relied on world-leading semiconductor companies to make high-end chips and provide equipment for its domestic manufacturing and software and tools for chip design.

Before the advanced chip ban implemented by the United States in October 2022, the Trump administration had in 2019 blocked key semiconductor manufacturing equipment such as EUV lithography machines from being sold to China. In August of 2022, the Biden administration further banned key electronic design automation (EDA) software (also known as electronic computer-aided design software) in chips design.

The chip ban changed the game fundamentally. It entirely cut off China’s access to the advanced chips it required for training of large language models (LLMs) and other AI foundation models. The sanctions were introduced just a month before the release of ChatGPT by OpenAI. Effectively, that launched a generative AI arms race between the United States and China. This battle between the world’s two superpowers is now well under way.

Because of continuing Chinese shortages of key equipment and components, the technological gap between Chinese companies and the international first-class chip companies has further widened. The most advanced AI chips, such as Nvidia’s H100, are manufactured with a more sophisticated 4 nm process by TSMC, and Nvidia’s latest B100 and B200 chips are reportedly using TSMC’s world-leading 3 nm process.

Compared with the 7 nm process, the 3 nm or the even more advanced 2 nm process can put many more transistors on each chip to achieve greater speed and computing power, which are crucial for the performance of these AI chips. More transistors bring about more functional units to get tasks done faster, hence performance increases. The world’s most advanced chip currently, the 4 nm-built H100, contains 80 billion transistors. Meanwhile, China is struggling to maintain its much less sophisticated 14 nm process for chip manufacturing.

In short, wide-ranging US sanctions have severely restricted China’s efforts to gain ground in almost every subsector of the chip industry, including in the manufacturing process, equipment manufacturing, advanced design software and tools. And the sanctions have also succeeded in denying Chinese access to imported high-performance AI chips.

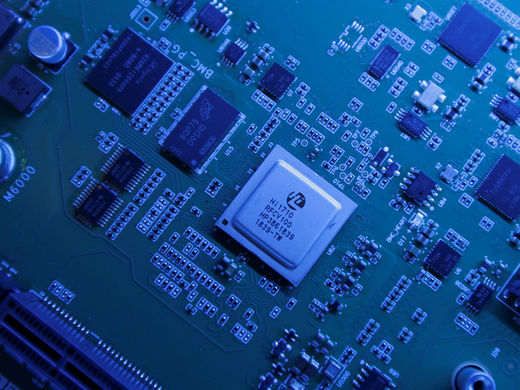

That being said, Chinese state-owned Huawei’s breakthroughs in the Mate 60 Pro smartphone in August 2023, following years of strict US sanctions, nevertheless surprised the world. The phone is equipped with Huawei’s own Kirin 9000s chips, fabricated with the 7 nm process by Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corporation (SMIC), China’s most advanced foundry.

This appeared to demonstrate that China had made a crucial breakthrough, despite sanctions. Along with the Mate 60, Huawei’s second-generation Ascend 910B AI chips, using the same SMIC 7 nm process released in late 2022, also shocked US officials.

A closer look at Huawei and SMIC’s surprising success, however, might have put the US policy makers at ease. The Financial Times reported in late November of 2023 that SMIC had used the less advanced deep ultraviolet (DUV) lithography machine and its second-generation 7 nm process to build 910B AI chips, which are typically manufactured using more advanced EUV lithography.

Simply put, using DUVs for the 7 nm process requires more manufacturing steps to place as many transistors as possible on each chip. Lithography, a crucial step in chip-making, is the process of transferring highly complex electrical circuit patterns onto silicon wafers. EUV machines can set patterns on a wafer using only a single exposure, while DUV machines require three or four rounds of patterning for a 7 nm chip. Multi-patterning generally involves more steps, which makes the process more complicated and less precise. It also consumes more time, materials and components.

For the Chinese government and its patriotic nationalists, the breakthrough was a slap in America’s face.

That largely explains why the production costs are so high and the yield rate — the percentage of working chips on a wafer — is so low , and why only a limited number of Ascend 910B AI chips were produced. With multi-patterning, more additional steps can lead to more defective chips on each wafer. With an exceptionally low yield rate of 20 percent (an ideal yield rate for chip mass production is close to 90 percent), this method of chip-making is not financially sustainable for mass production. It most likely was done to demonstrate greater capacity than actually exists.

The point is that it appears the Chinese government picked up the cheque for the chips fabricated with this extremely low yield rate. The inordinate cost was likely considered the price of scoring a political victory and bolstering national pride. For the Chinese government and its patriotic nationalists, the breakthrough was a slap in America’s face, showing that US attempts to slow China’s technological advancement haven’t worked. Huawei, for its part, was able to flex its muscles and retain market share and standing in the global semiconductor supply chain, in particular on AI chips. SMIC saw an increase of its revenue and demonstrated its innovative capacity as China’s top foundry.

Huawei and SMIC now stand as China’s best hope in producing advanced AI chips. But catching up to the United States won’t be easy, even with strong state support. In the crucial area of chip manufacturing, SMIC only began large-scale production of 14 nm chips in 2022, and its mature production remains with the 28 nm process, still one to two generations behind. With regard to chip design, Huawei had been an important player in the global market for products such as its system-on-a-chip for smartphones, 5G (fifth-generation) chips. But the company now faces bottlenecks in crucial design tools, such as EDA software, and in processor architecture from ARM, a UK-based chip designer. Like ASML in the Netherlands, to which the US government asked not to sell advanced EUV lithography machines to China, ARM was also required by the US government to align with the latter’s chip ban.

In terms of lithography equipment, 90 nm-process lithography machines made by Shanghai Micro Electronics Equipment (SMEE) are the mature domestic product for mass production in China. The best China can do at present is the lithography machine for the 28 nm process, which was reportedly being developed by SMEE at the end of 2023. But it will still take years before it can be delivered for mass production for 28 nm chips with a decent yield rate, while ASML has already delivered its latest EUV lithography for 2 nm process in 2024. The gap between SMEE and ASML remains at about two decades.

Moreover, the sanctions are likely to remain in place for years to come. Chinese companies thus must either use less advanced AI chips, such as Nvidia’s H20, which is customized for the Chinese market and not on the sanctions list, or wait for Huawei and SMIC’s supply of Ascend 910B, which have experienced shortages. Or they must hope for a slight easing of sanctions effects, due to less than perfect cooperation from reluctant allies such as Japan, the Netherlands and South Korea. There may also be lobbying pressure from the US semiconductor sector, which opposes sanctions.

A fundamental change of course to improve political relations with US-led democracies and join the advanced-chip supply-chain ecosystem could also help, if it brings matters back to the pre-trade war era, before 2018. But this is a long shot and not likely to occur any time soon, given the complexity of the geopolitical situation and domestic politics in both the United States and China.

That means China will likely continue to double down on homegrown innovation in chip equipment and manufacturing, as best it can. In the meantime, the West’s lead seems insurmountable, as long as China remains isolated from the global semiconductor ecosystem.