Following a period of democratization in the late 1990s, democracy is now rapidly waning in former Eastern Bloc countries, including Hungary, Serbia and, to a lesser extent, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo and North Macedonia.

Eastern and Southeastern Europe, the Western Balkans in particular, are home to geopolitical disputes, polarized internal politics and ethnic tensions that make them fertile ground for digital violations, including disinformation, online harassment and surveillance. Indeed, according to a 2021 European Parliament study of disinformation, it “thrives most virulently … in environments that are already riven with internal conflicts, and where social and public trust already struggles to bridge political, regional, ethnic, religious or other divides.”

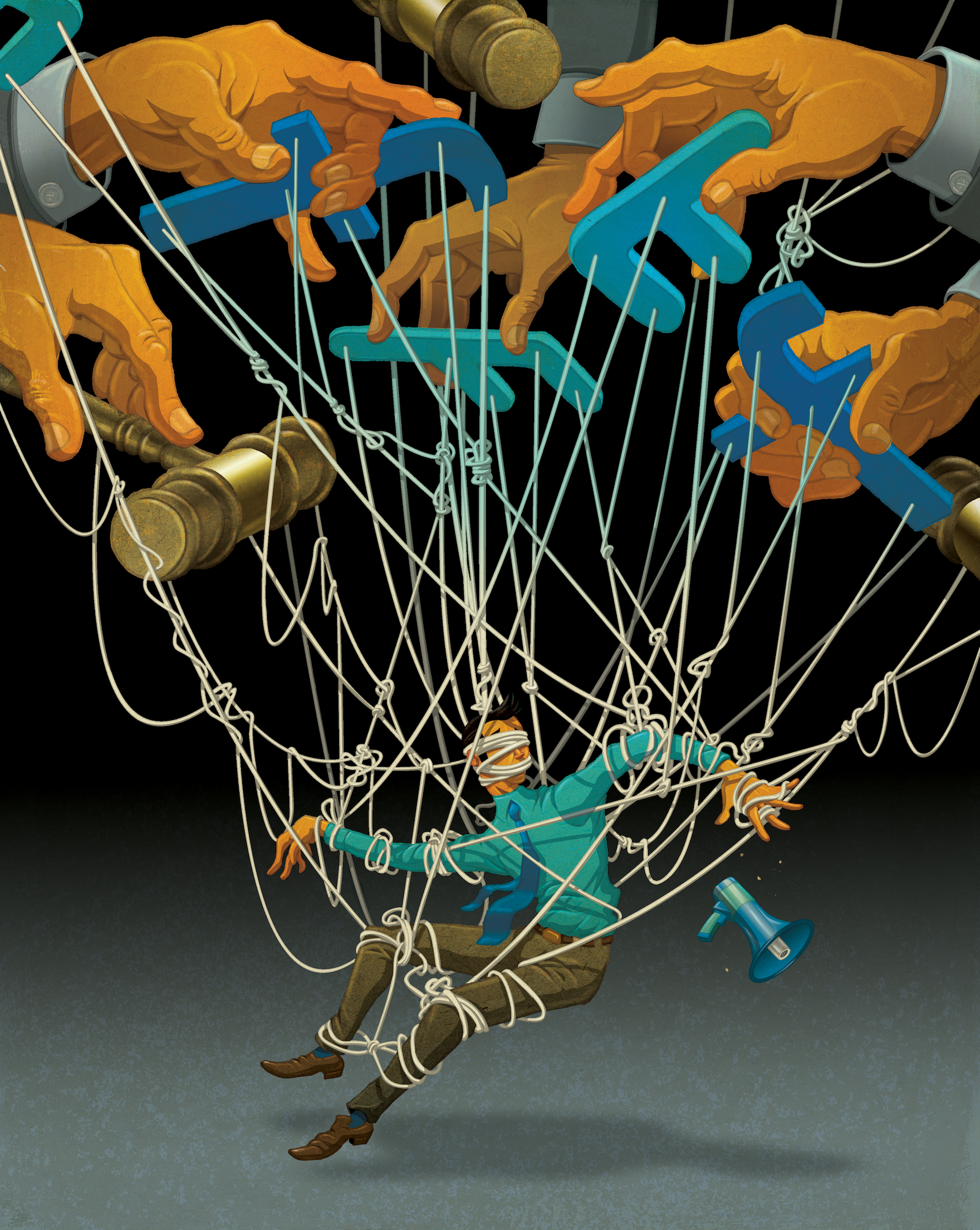

Domestic actors are taking advantage of these fault lines to attain and maintain power, control public opinion, and pursue other political ends, increasingly using social media and the internet.

Through a range of uses from disinformation campaigns and harassment to spyware and facial recognition, information and communications technologies (ICTs) and surveillance technologies are playing a growing role in the decline of democracy in Eastern and Southeastern Europe.

Hungary

Prime Minister Viktor Orbán’s admiration for Russian President Vladimir Putin is no secret. In 2019, Freedom House ranked Hungary as “partly free” in its annual Freedom in the World report — an unprecedented score for a member of the European Union. Since his election in 2010, Orbán and his party, Fidesz, have passed a myriad of legal and constitutional changes in order to remain in power. The justice system is no longer independent. Fidesz dominates the political and media landscape, and Central European University, an independent international university that had had a campus in Budapest, was forced to leave the country.

In Digital Rights Falter Amid Political and Social Unrest, a regional analysis conducted by the Balkan Investigative Reporting Network (BIRN) and the SHARE Foundation, researchers documented the alarming rate of digital violations occurring in Hungary. Between August 1, 2019, and November 30, 2020, these organizations verified 173 such cases, in particular of “pressures because of expression and activities on the internet” and online manipulation and propaganda.

In a later report, Online Intimidation: Controlling the Narrative in the Balkans, these organizations reported 150 additional cases between August 1, 2020, and August 31, 2021. Researchers noted an alarming rate and wide range of online hate speech, denial-of-service attacks, account suspension, discrimination, and falsehoods posted online with the intention of damaging reputations.

As Freedom House, BIRN, the SHARE Foundation, and numerous other organizations as well as journalists have demonstrated, opposition politicians, media, academics, civil society groups and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) have been the target of online and offline threats and smear campaigns coming from pro-Orbán political figures and supporters. Indeed, Online Intimidation reports that “almost 78 per cent of the media is pro-government and thus willing to wage war on political opponents — including the EU and NGOs — on the government’s behalf.” The SHARE Foundation’s database records numerous smear campaigns led by pro-government media and political figures against political adversaries, independent media and civil society groups.

One of Hungary’s largest independent news websites, Index.hu, is now primarily owned by a pro-government businessman. In the regional analysis by BIRN and the SHARE Foundation, a contributor wrote that the purchase of the site, once considered a symbol of freedom, “meant more than just the latest restriction of the free, digital media in Hungary. It meant the dreams of 1989 and the modicum of progress made since then were being undone.”

The SHARE Foundation continues to monitor online violations. The foundation’s policy researcher, Bojan Perkov, told me that the most common digital rights violations remain hate speech and threats, smear campaigns, and lawsuits related to online content. But new threats are emerging. In July 2021, a large-scale investigation by a consortium of journalists, including the Hungarian outlet Direkt36, revealed that countries around the globe had purchased Pegasus, spyware made by the Israeli company NSO, which allows the operator to take control of a target’s mobile device and access all its data. In Hungary, the government bought the spyware not to surveil terrorists or serious criminals but to target journalists, lawyers and activists.

Particularly worrying is that Orbán has not done anything illegal, per se. Instead he has changed the law to suit his ends. This included adopting new legislation against “scaremongering” during the COVID-19 pandemic — a clear attack on media freedom, because the law can be used to demonize accurate reporting as “fake news” and scaremongering. The government also called for national regulation of Facebook to prevent the platform’s restriction of content it deems “hateful.” According to the government, Meta’s decision to take down certain content is evidence of a “global conspiracy to silence the Hungarian government.”

Why should we care about what’s happening in Hungary? Because, as the journalist Anne Applebaum noted in 2020, although it’s a small country, “it is one whose creeping authoritarianism is widely admired.”

Journalists and activists are routinely threatened via political pressure that is often instigated by members of the ruling political class.

Serbia

Hungary’s southern neighbour, Serbia, may be following a similar path. Since 2012, the Serbian Progressive Party (SNS) has used the memory of devastating wars of the 1990s — with a strong dose of historical revisionism portraying the Serbian nation as a victim — to gain political legitimacy. In the digital age, the internet and social media are used “for the purposes of memory politics and dissemination of war narratives, making all commemorative practices more widely and easily accessible than ever before,” according to a study by the Humanitarian Law Center in Belgrade, Memory Politics of the 1990s Wars in Serbia.

Since the election of Aleksandar Vučić as president in 2017, political power has been increasingly concentrated in his hands and his party, the SNS, greatly centralizing the country’s political system. Vučić and pro-government media have been credibly accused of using authoritarian tactics to silence political opponents, independent media, civil society and activists. Consequently, Freedom House in 2019 downgraded Serbia’s status from a partial democracy to a “hybrid regime.”

Party-affiliated media outlets, combined with domestic and foreign-networked online disinformation, have proven particularly useful to Vučić and his party, according to a 2020 study by the Stanford Internet Observatory titled “Fighting Like a Lion for Serbia.” Triggered by Twitter’s announcement in March 2020 that it had taken down disinformation networks targeting Serbian users of the platform, the study shows that this organized campaign boosted Vučić’s election chances by attacking his political opponents and ramping up positive Twitter content linked to the then-candidate. As a European Parliament study noted, in a political system dominated by one party, media and social media narratives “serve the interests of the ruling party and its allies.”

Journalists and activists are routinely threatened via political pressure that is often instigated by members of the ruling political class, according to the BIRN/SHARE Foundation’s 2020–2021 study. Indeed, of all the countries monitored by the SHARE Foundation, “Serbia has the highest rate of online attacks against journalists.” Politicians such as Vladimir Orlić, a Serbian Progressive Party member of Parliament, and Nikola Sandulović, Serbian Republican Party president, have used Twitter and Facebook to attack investigative journalists. Particularly concerning is the number of online death threats journalists receive.

As in Hungary, the Serbian government uses the law to intimidate activists and journalists seeking to uncover abuses of power. Between 2010 and 2020 in Serbia, at least 26 civil lawsuits were brought against journalists, media outlets and civil society organizations, according to ARTICLE 19, which reports that SLAPPs — strategic lawsuits against public participation — “are becoming an all too common tool for the rich and powerful to stifle critical voices in the country.” Legal harassment is becoming one of the favourite tools in the digital authoritarian toolbox.

While there isn’t widespread evidence in Serbia of the use of advanced spyware against journalists and activists, the country has a dubious track record in this regard. In 2013, Toronto-based research centre the Citizen Lab found that Serbia’s Security Information Agency is a client of FinFisher, an intrusive surveillance software that has been used in multiple countries to target human rights activists. In 2015, a SHARE Foundation investigation titled “Invisible Infrastructures: Surveillance Architecture” showed the various ways in which Serbia’s biggest telecommunications service allowed state bodies access to Serbian citizens’ metadata, including through data requests, physical tracking in real time and wiretapping. In yet another surveillance case, researchers at the Citizen Lab and from Google’s Threat Analysis Group uncovered in 2021 that Predator, a spyware tool developed by Cytrox, had been sold to Serbia, where it could have been used to spy on political opponents or journalists, although no concrete evidence of such use exists.

Of particular concern is Serbia’s growing relationship with Beijing. Although Serbia still conducts two-thirds of its foreign trade with the European Union, China is regarded as an important economic partner, including when it comes to new technologies. A 2020 study from the Washington-based Center for Strategic & International Studies (CSIS), Becoming a Chinese Client State, shows that increased Chinese economic activity in Serbia is shaping the country’s ICT network and policies that guide them.

Serbia is not simply adopting a pro-China political rhetoric; it is also adopting Beijing’s anti-democratic norms and digital infrastructure. According to the report, Chinese technology companies, including Huawei and Tencent, regard Serbia as a gateway to Southeast Europe. Chinese ICT projects in Serbia include data centres, an AI training centre and 5G (fifth-generation) mobile infrastructure, among others. In view of Huawei’s poor security record, there are clear reasons to worry about the government’s use of citizens’ data. The CSIS report concludes that “China’s technology exports erode Serbian civil liberties … by amplifying the state’s ability to track and suppress citizens and intimidate critics of the governments.” If Serbia is, as SHARE Foundation representatives quoted by CSIS believe, “an ideal testing ground for [Huawei surveillance technology] on the whole continent of Europe,” there are indeed reasons to worry about who is next.

This entrenched political situation, combined with anti-liberal sentiment across the media landscape, makes Bosnia and Herzegovina particularly vulnerable to domestic and foreign influence, online hate, threats and harassment.

Bosnia and Herzegovina

Unlike Serbia, Bosnia and Herzegovina’s political system is structured around ethnic and sectarian divides, making it extremely decentralized. Set up after the 1992–1995 war, the country is organized into two autonomous regions: the Federation of Bosnia–Herzegovina (the Federation) and the Serb-dominated Republika Srpska (RS). In addition, there is one semi-autonomous district and 10 local government cantons in the Federation. The presidency of Bosnia and Herzegovina is a three-member body comprised of one Serb, one Bosniak and one Croat.

This entrenched political situation, combined with anti-liberal sentiment across the media landscape, makes Bosnia and Herzegovina particularly vulnerable to domestic and foreign influence, online hate, threats and harassment. Ethnic tensions have increased in recent years, with RS, Bosnia’s Serb-dominated entity, willing to withdraw from crucial institutions such as the judiciary and security service. It should be noted that Milorad Dodik, the Serb member of the presidency of Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Željka Cvijanović, the current president of the RS, have both been sanctioned by Britain for undermining peace and encouraging ethnic hatred, including by pushing for the de facto secession of the RS.

According to a study on disinformation in Bosnia and Herzegovina conducted by the European Parliament, political actors, public figures and public media from the country’s three communities actively exploit existing divisions to advance their political goals, for financial gain, or in the case of the RS in particular, to amplify pro-Moscow and pro-Serbia messages. The study shows, for example, that Milorad Dodik, the Bosnian Serb member of the tripartite presidency, is often presented in a positive light in media manipulations.

According to the SHARE Foundation’s online violations monitor for Bosnia and Herzegovina, ethno-nationalism and ethnic tensions “poison Bosnian society, both on and off the web.” The most common digital rights violations are hate speech, discrimination, manipulation and threatening content. Journalists have received death threats on social media platforms. The international NGO Civil Rights Defenders reports that hate speech and harassment against human rights defenders and journalists have indeed increased, particularly as a result of growing pressure from the government, institutions and citizens. Social media has become the predominant channel for such threats.

As in Hungary and Serbia, political leaders have tried to co-opt anti-disinformation legislation to silence criticism. In 2020, Željka Cvijanović passed a decree in the RS forbidding the media and the general public from spreading false news that incites panic during the COVID-19 state of emergency. In the country’s other entity, the Federation, the government monitored content on social networks and launched five criminal proceedings for allegedly spreading false information and panic.

The effects on democracy and freedom of speech can be devastating, as offline ethnic and political tensions tend to be amplified on social media. This is all the more true for Bosnia and Herzegovina, where political bots and astroturfers, as well as anonymous websites known as “portal farms,” are “a driving force for the expansion of ‘disinformation landscape.’” According to SHARE’s 2021 digital rights report, “fake and biased reports are published to instil fear of other ethnicities, stir up hatred and reinforce the message that only particular political parties will protect ‘their own’”; further, ahead of local elections and during the COVID-19 crisis, “there was certainly no lack of rhetoric referencing the horrific events of the 1992–5 war to stoke fears of renewed violence and ram home the message that only particular parties would protect particular groups.” Particularly worrying is a rise in denial of the 1995 Srebrenica genocide. As the New York Times recently noted, Bosnia and Herzegovina is on the brink.

Civil Society Organizations Resist

If there is hope for Hungary, Serbia, and Bosnia and Herzegovina, we must look to journalists, fact-checking projects, public education initiatives and other actors determined to fight for digital rights, democracy and freedom of expression. That’s especially important as governments tend to use anti-disinformation and anti-hate speech regulations to protect their own interests and to silence those they perceive as a threat. Investigative journalism and research NGOs such as Atlatszo in Hungary, KRIK in Serbia and Raskrinkavanje in Bosnia and Herzegovina are determined to persevere. Serbian citizens have launched the “Hiljade kamera” (“Thousands of Cameras”) platform in response to the deployment of facial recognition surveillance in Belgrade. Supported by the SHARE Foundation, the project’s aim is to combat biometric video-surveillance in public spaces.

SHARE and BIRN should be commended for their work in monitoring digital violations in the region, despite the pressures they may experience. The two organizations created the SEE Digital Rights Network with the aim of bringing together human rights and civil society organizations to fight for digital and human rights.

In the age of social media, mass surveillance and a global decline in democracy, including in former Eastern Bloc countries, it seems clear that we must once again count on citizen-led movements and journalists to combat the worst abuses of technology. With the wave of optimism of the 1989–1991 years fading into history, citizens are nonetheless working vigorously to prevent their governments from reversing their countries’ hard-won progress and being pulled back into full authoritarianism.