Pipeline construction in Canada is a source of conflict between state law and Indigenous peoples attempting to craft solutions to environmental challenges pursuant to their own legal systems. Two examples in particular illustrate how the relationship between state and Indigenous laws play out in the context of pipeline development: the Trans Mountain pipeline expansion and the Coastal GasLink pipeline show how Indigenous legal orders are sidelined from, or minimized within, decision-making processes. In showing the limitations of current approaches, however, these projects also provide a glimpse of alternative possibilities for co-existence between state and Indigenous legal regimes.

The Trans Mountain Pipeline Expansion

The Trans Mountain pipeline expansion process represents the high end of the duty to consult in relation to resource developments affecting Aboriginal rights. After approval of the multibillion-dollar project had been recommended by the National Energy Board (NEB), and granted by the federal government, a number of Indigenous nations challenged the project on the basis that Crown consultation and accommodation had been inadequate. The Tsleil Waututh et al. won at the Federal Court of Appeal (FCA), a victory that resulted in the project being halted.

The FCA emphasized the importance of dialogue in the consultation process. It was not enough that the federal government listened to Indigenous peoples’ concerns — it needed to engage in a dialogue about those concerns and demonstrate through its actions that the planning and execution of the project took those concerns into consideration. This is a robust conception of consultation that goes beyond merely seeking out information.

Despite this, there was a limited role for Indigenous legal orders in the decision-making process. Immediately following the decision, for example, federal Minister of Finance Bill Morneau told reporters that the pipeline “will be built.” How could he say this with certainty? The rest of his statement gives some indication: “[the pipeline] needs to go through a process that ensures we consult appropriately and engage appropriately as identified by the court this morning.” But, if this consultation process had not yet begun, how could the outcome — that the pipeline “will be built” — already be determined?

It was not enough that the federal government listened to Indigenous peoples’ concerns — it needed to engage in a dialogue about those concerns...

The answer was foreshadowed by the concluding paragraph of the decision. There, the court held that a “brief and efficient” consultation process would allow the project to proceed. The process did not require that Indigenous peoples approve of the project, only that they be consulted. Indigenous law, to the extent that it might reject the project, was thereby excluded from the process. Indigenous law cannot determine the outcome if that outcome differs from that reached by state law.

The assumption that the Crown may act unilaterally in the face of Indigenous opposition shapes the duty to consult. If Indigenous peoples decide, according to their own laws, that a project may not proceed, the imposed hierarchy of laws immediately presents itself: to the extent that Indigenous laws may respond to the environmental harm, the scope of those protections are limited by state law. While the Tsleil-Waututh et al. won this decision, the decision clearly indicated that further consultation may allow the project to proceed regardless of whether the Indigenous parties consent to it or not.

As of this writing, the project has been re-approved by the NEB and the federal government has yet to conclude renewed consultation efforts. While subsequent efforts may satisfy a court, there are strong indications that they may not satisfy Indigenous parties. What happens then? If a First Nation challenges the re-approval on the basis of inadequate consultation and the court dismisses their claim, the project may go ahead. The nation might then seek to stop the project by bringing forward an infringement claim. Whereas the duty to consult arises where asserted rights are in play — obviating the need for a judicial determination of the scope of the rights at issue — it would remain open to a First Nation to allege an infringement of their rights subsequent to a ruling that went against them on the duty to consult.

The first step in bringing an infringement claim would be to demonstrate the existence of the right in question. This would require satisfying the Van der Peet test, which has been roundly criticized for tying Aboriginal rights to Indigenous cultural features at the time of European contact. Specifically, the test requires that a given activity be proven to be “integral to the distinctive culture” of the group in question at the time of contact. This is an onerous and costly burden to meet. If an infringement of a right can be demonstrated, it is then open to the Crown to argue that the infringement is justifiable on the basis of a minimal impairment test.

The presumption under the Sparrow and Van der Peet frameworks is that the state retains the authority to act unilaterally even where rights are established. While this concept has infrequently been supported in practice, the underlying presumptions shape a consultation framework in which outcomes are pre-determined. Projects “will be built” once the procedural requirements of consultation have been fulfilled. This presents enormous challenges for Indigenous peoples seeking to respond to environmental challenges through their own legal regimes or the rights paradign in section 35 of the 1982 Constitution Act. The experience of the Wet’suwet’en and the Coastal GasLink pipeline provides another vantage point on this issue.

Coastal GasLink

The planned Coastal GasLink pipeline would transport natural gas from Dawson Creek to Kitimat, British Columbia. In January 2019, Wet’suwet’en peoples were forcibly removed from the path of the pipeline. This conflict showed the displacement of Indigenous law in two ways. The first was the displacement of traditional governance institutions with imposed Indian Act governance. The second was the imposition of a rights regime that excludes Indigenous modes of tenure and jurisdiction until they are proven in court through an Aboriginal title analysis.

One important aspect of the January conflict was that Wet’suwet’en Indian Act governments entered into agreements allowing the project to proceed, while the leaders of the traditional institutions of governance did not. A clear conflict between Canadian state law and Indigenous legal orders thereby arose when the state sought to rely on approval by the band government to support the project. In the media, this was covered as a conflict between Indian Act and “hereditary” forms of government. In discussing potential Indigenous solutions to environmental harms, it is important to understand what these hereditary forms of government are.

A second notable displacement is in the interpretation of Wet’suwet’en rights. Part of the justification for the Royal Canadian Mounted Police removing Wet’suwet’en peoples from the pipeline path was that they have not established rights in the area. This is a cruel irony for a couple of reasons. First, the Wet’suwet’en fought for recognition of title in that territory for more than a decade in the Canadian courts, only to have the Supreme Court of Canada (SCC) send the matter back to trial for procedural reasons despite articulating a conception of title that the evidence in the case likely satisfied. It appears the court may have been playing a political game in Delgamuukw, warning governments to negotiate Aboriginal title claims in good faith and resolve outstanding title claims. While the court recognized that the houses were legitimate title holders and that Wet’suwet’en title had never been extinguished, no declaration of title was made. The protections afforded under Canadian law were, therefore, severely limited.

Where Canadian law has not yet recognized rights or title, Canadian law prevails unequivocally.

Comparing this to the situation of the Tsilhqot’in provides further clarity. The Tsilhqot’in received a declaration of Aboriginal title in 2014. The SCC held that where title has been established, Aboriginal consent is required before any development can move forward. While this consent could still be bypassed by justifying an infringement, the protections afforded are substantial. Contrast this with the situation of the Wet’suwet’en, who were forcibly removed from their territories by militarized police. Against the backdrop of a discussion of Indigenous legal solutions to environmental harms — and amid the implementation of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples — the contrast is striking. Where Canadian law recognizes a title interest (which it itself defines), then room may be created for Indigenous law to prevail. But, where Canadian law has not yet recognized rights or title, Canadian law prevails unequivocally. Where the pipeline on Wet’suwet’en territory is concerned, that law defines the lands in question as Crown lands, determines that there are no relevant established rights that need to be taken account of, and exercises the power of the state to push contested projects through. Again, the imposed hierarchy of legal systems can be seen.

Making Space for Indigenous Law

The above examples illustrate some of the ways that contemporary state law in Canada minimizes or excludes Indigenous legal orders and, with them, Indigenous solutions to environmental challenges. To the extent that Indigenous law deviates from the state’s chosen path, it is simply bypassed. Yet, these examples also show where other possibilities may exist.

In the Trans Mountain decision, the FCA remarked that Indigenous environmental assessments could provide an outline for accommodation under the duty-to-consult framework. As Sharon Mascher discusses in this collection, this would provide an avenue for expressions of Indigenous law to influence the decision-making process. The situation of the Wet’suwet’en illustrates the potential in the Aboriginal title doctrine. By recognizing traditional governance institutions as title holders, the court has opened the door to recognizing the jurisdiction to those groups in traditional territories. Meeting these optimistic visions, however, would require a foundational shift. In each case, the power of the state to act unilaterally cannot continue to shape legal doctrine. To the extent that legal doctrine continues to be shaped by the presumption that the state may act unilaterally, the transformational possibilities alluded to will remain latent, and the ability of Indigenous peoples to shape solutions to environmental challenges according to their own legal traditions will remain circumscribed by the state.

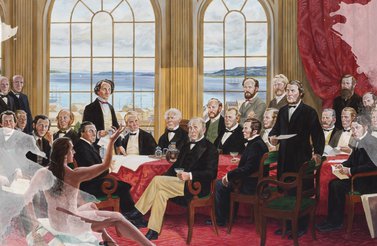

About the artist: Kent Monkman, born in Canada in 1965, is a Cree artist who is widely known for his provocative interventions into Western European and American art history. He explores themes of colonization, sexuality, loss, and resilience — the complexities of historic and contemporary Indigenous experiences —a cross a variety of mediums, including painting, film/video, performance and installation.