As a young child growing up in Kuujjuaq, Que., in Canada, I travelled only by dogsled for the first 10 years of my life. I was often snuggled into warm blankets and fur as my family set out on hunting and fishing trips. The vast Arctic sky surrounded us and the ice held strong beneath our feet – the foundation that carried us across the frozen land.

For the Inuit, ice is much more than frozen water; it is our highways, our training ground and our life force. It’s something we thought to be as permanent as mountains and rivers in the south. But, in my generation, the Arctic sea ice and snow, upon which we Inuit have depended for millennia, is now diminishing.

Dramatic climate change has left no feature of our landscape or our way of life untouched and now threatens our very culture, our ability to live off the land in safety. While the Arctic may seem cold, dark and distant for most, for us it is our beloved homeland which provides all that we need for our physical, spiritual and cultural well-being.

In various speeches I delivered as an elected official of the Inuit Circumpolar Council at United Nations forums, Arctic Council-related events and other international forums, I would say what is happening here is a glimpse of what is to come.

For a variety of alarming reasons, temperatures are rising faster at the North and South Poles compared to other parts of the world. In early June, my hometown of Kuujjuaq was 28.4 degrees, making it the hottest spot in Canada that day. In all four regions where the Inuit live – Northern Canada, Alaska, Greenland and Siberia – every community is struggling to cope with extreme coastal erosion, melting permafrost and rapid runoff as temperatures rise.

The frozen permafrost that used to serve as a reliable foundation is destabilizing homes and other structures. As the coastline erodes buildings have cracked and fallen into the ocean like a scene out of a sci-fi thriller, but sadly this is not a movie.

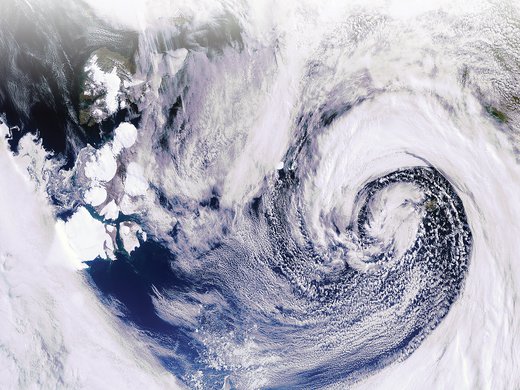

In order to arrest this dangerous trajectory, the world has to take note of what is happening in the Arctic – because what happens in the Arctic doesn’t stay in the Arctic. It’s the planet’s air conditioner and as it melts it causes havoc on the world.

We are constantly reminded how taking action on greenhouse gas emissions will negatively impact our economy. This is a lame and outdated card to play at this late stage of our climate crisis. The human, environmental and economic costs are racking up around the world and need to be properly accounted for.

Ultimately, addressing climate change and building human rights protections into our global climate agreements is not just a matter of strategy. It is a moral and ethical imperative that requires the world to take a principled and courageous path to solve this great challenge. As more leaders lose sight of the larger and longer-term picture with great economic potential in sight, staying on the principled path will become increasingly difficult for many. This, I believe, is the test of our time.

Given that the United States has walked away from the Paris Agreement and other governments have been slow to act, recent cases in the Netherlands, Colombia and the U.S. suggest that climate litigation may increasingly be seen as an essential tool to protect human rights and to safeguard the environment.

In 2005, I led the pioneering work on connecting climate change to human rights by putting forth a legal petition to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights. The Inuit’s right to be cold is connected to everyone’s right to a healthy and safe environment. If we protect the Arctic we save the planet.

Inuit and Indigenous peoples provided life-saving guidance to early European visitors unfamiliar with the severe conditions, which they ignored at their peril. The Inuit still have much to teach the world about living harmoniously with the land and the vital importance of the Arctic ice. The world needs to reimagine and realign economic values with those of the Indigenous world and Inuit world, rather than replicating what hasn’t worked with the values of Western society. This holistic Indigenous wisdom needs to be adhered to as the world seeks solutions towards a sustainable world. Are you ready to listen?

The article originally appeared in The Globe and Mail.