At least one million people have died from coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) since January 2020. Many more will die before we find better ways to manage or eradicate this disease, although eradication seems increasingly unlikely. This is a tragedy of almost incomprehensible proportions.

That tragedy has combined with another potentially life-threatening problem — an alarming quantity of poor-quality and often directly harmful information about the pandemic and quack cures. World Health Organization (WHO) Director-General Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus warned back in February about this “infodemic.” This warning came a few weeks before the WHO declared in mid-March that COVID-19 was a pandemic, meaning a global epidemic.

The infodemic, too, appears to have had real health consequences: one study, published in August 2020, estimated that alcohol poisoning killed almost 800 people from around the world who apparently believed an online rumour that drinking highly concentrated alcohol would prevent COVID-19.

The word infodemic is not the first term to describe our online world that has been borrowed from health. During the pandemic, researchers have talked about how social media companies should “flatten the curve” of misinformation. We talk about computer viruses and, in fact, that terminology emerged in the 1990s from an analogy to the HIV/AIDS pandemic, as Cait McKinney and Dylan Mulvin have shown. McKinney and Mulvin argue that “HIV/AIDS discourses indelibly marked the domestication of computing, computer networks, and nested, digitized infrastructures.”

Too often, platforms appropriate medical language. Twitter has talked for several years about wanting to promote “healthy conversations.” But what does healthy mean online?

Content on social media platforms is indeed only one part of the ecosystem, which also includes questions around tax policy, surveillance, antitrust, company culture and so on.

One way to grapple with this problem is to draw inspiration from other concepts in public health. One potentially helpful concept is “One Health.” One Health has multiple definitions, but at its most basic it is “an approach to ensure the well being of people, animals and the environment through collaborative problem solving — locally, nationally, and globally” (this is the definition from the One Health Institute at the University of California, Davis). The One Health idea sounds similar to many Indigenous and other ways of knowing that see humans as inextricably linked to surrounding animals and environment — a new name for very old concepts.

However, very little discussion of COVID-19 beyond scholarly circles has evoked the One Health idea. This is strange in many ways because it has existed as a specific term for several decades and was crucial in much of the drive to create global influenza response systems. The concept matters because COVID-19 can only really be understood as part of a broader ecosystem of human interactions with nature that have accelerated the emergence of zoonotic diseases such as COVID-19.

COVID-19 is neither unprecedented nor a one-off. Seventy-five percent of the emerging pathogens over the past few decades have been spread from animals to humans. These include epidemics such as Ebola and Zika virus disease. One Health encompasses more than just novel pathogens that are emerging from human encroachment upon new environments. Researchers have also considered how global food practices often create deadly foodborne diseases: more than 400,000 people die annually from contaminated food. The stakes of addressing public health problems through One Health are incredibly high.

If we continue a long-standing trend of using health concepts and language to think about the online world, what can the One Health concept contribute to platform governance?

If we follow the One Health concept, we see that COVID-19 is only one example of how human interactions with animals and our planet accelerate pandemics. Rather than portray COVID-19 as an incident to be overcome and forgotten like the 1918 flu pandemic, One Health reminds us to understand COVID-19 within the context of both climate change and increasing human encroachment into animal and plant habitats. COVID-19 is the latest in a series of such problems, like the earlier coronavirus outbreaks (SARS in 2003 and MERS in 2012) and Ebola. Governments, companies and citizens can muddle through this pandemic and just hope (almost certainly in vain) that another does not arise. Or they can reckon with the One Health approach that demands systemic change to prevent such pandemics.

Applying the One Health logic to platform governance means looking beyond individual examples of content that so often rise to the top. One platform may seem to cause an infodemic. But the reality is far more complex and intertwined. A One Health approach to platform governance means seeing platforms as part of our social, political and economic ecosystems. Dealing with Facebook alone would be like addressing COVID-19 but nothing else — no regard for economic recovery, improved infrastructure or the changing relationship between humans and animals. It might seem to work for a time, but the impact of the virus, or other viruses like it, would surface again. Just like systemic understandings of viruses remain fundamental to our response to COVID-19, a systemic understanding of the platform ecosystem — and how it interacts with the offline world — remains fundamental to address our problems of platform governance.

Platforms

In May, the video Plandemic was released online and viewed by more than eight million people within seven days. The video featured a discredited doctor, Judy Mikovits, and was packed full of problematic assertions. Her assertions underplayed the gravity of COVID-19 as a disease and could have potentially serious consequences for anyone who believed them. When a sequel to Plandemic was released in August, platforms like YouTube were ready, and the video attracted far less attention.

The management of the Plandemic videos might seem like a story of success: platforms seemed to learn from the first outing. But these videos comprise just one very specific example of problematic content. Celebrating individual wins of removing posts or successfully combating a single conspiracy video is akin to focusing on how, say, one group of people has isolated to stop COVID-19 while creating policies, such as in-person university teaching, that enable many more cases. One online conspiracy may be gone, but then another pops up, such as the recent campaign on Facebook and Instagram urging people to burn face masks on September 15. The online focus on individual cases often comes at the expense of attending to the algorithmic and other systemic reasons why such cases keep occurring.

Moreover, content like the Plandemic videos constantly places the pressure on actors outside platforms — in this case, scientists, to debunk the claims in the video, or journalists, to detect problems in the first place. Such examples resemble the phenomenon of sports: the NBA or the US Open can afford to create a successful bubble, but such instances only work for high-profile cases which attract millions of viewers. Pushing actors with fewer resources to address each problem serially only obscures the question of when, not if, such problems will recur.

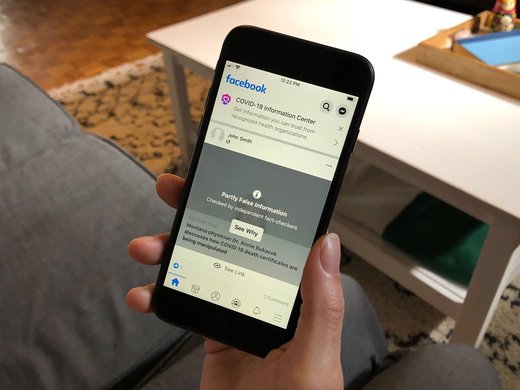

The One Health approach reminds us to look holistically. Instead of focusing on individual posts, policymakers must consider the ecosystem, risk tolerance and infrastructure that allows harmful or untrue information to proliferate. Facebook recently noted that it has removed one million groups in the past year for violating its policies. Quarterly and annual reports from many platforms similarly detail how much hate speech or other types of forbidden speech they’ve removed from the platforms. So the larger questions would go beyond whether platforms have succeeded in removing all the hate speech posts, and address instead what it is about the ecosystem that enables so many of these posts to exist in the first place, and examine where this content has cropped up most virulently around the globe.

One Health means that a health problem anywhere in the world can become a problem everywhere in the world. Similarly, many of the problems now coming to roost in North America and Europe have happened elsewhere. Generals in Myanmar used Facebook to push for mass expulsions of the Rohingya in 2017. Hatred spread quickly in Myanmar over Facebook for many reasons, including that the company did not have content moderators with the language skills or local contextual knowledge to understand what was happening.

Too little was learned from this terrible tragedy. This summer, messages of hate on Facebook were proliferating in Ethiopia and seem to be stoking violent ethnic tensions. Of course, Facebook is not solely to blame for the intertwining of political and ethnic tensions within Ethiopia. But the Africa policy lead for Access Now, a digital rights group, said in September that “when the violence erupts offline, online content that calls for ethnic attacks, discrimination, and destruction of property goes viral. Facebook’s inaction helps propagate hate and polarization in a country and has a devastating impact on the narrative and extent of the violence.”

Ignoring the global context of online platform behaviour has proven short-sighted. Just as One Health advocates following basic rules for improving human interactions with our environment, platforms should apply certain basic rules for their interactions before entering a new environment. Facebook’s Community Standards are not even available in Ethiopia’s two main languages, so Ethiopians cannot even reasonably be expected to understand what is or is not allowed on the platform. Only now does Facebook seem to be hiring content moderators who understand the local context and actually know Ethiopia’s two main languages. Unless Facebook moves very quickly, what happened in Myanmar becomes a playbook for Ethiopia.

Such problems are not limited to any one continent. After a Black man was seriously injured by police in Kenosha, Wisconsin, in August 2020, protests broke out. But Facebook groups also sprung up online to encourage people to “protect” communities through violence. Despite pleas from journalists and concerned individuals, Facebook took its time to remove these groups. In the interim, a young man of 17 had driven to Kenosha and shot two Black protestors. We do not live in a hermetically sealed world, but too many people living in North America and Europe believed that hate speech in “other places” could not inspire violence in the same ways. However, like disease, information has a habit of travelling, and its consequences can be severe. This does not mean that all content moderation policies must be the same all over the world but that we must pay attention to how techniques of hate can spread almost as quickly as pathogens.

Content on social media platforms is indeed only one part of the ecosystem, which also includes questions around tax policy, surveillance, antitrust, company culture and so on. These matters, too, deserve scrutiny, because content alone cannot explain our problems. Even more broadly, we might consider the problematic incentives of a venture capital culture that looks for unicorns and encourages astronomical, relentless growth.

The Media Ecosystem

Just as One Health sees the health of humans as connected to that of animals and the environment, so too we must view platform governance within the context of the surrounding media, political, economic and social ecosystems. Platforms are part of a broader media ecosystem with deep problems of its own in many countries. In some cases, journalists cover conspiracy theories or fringe movements for their novelty, but doing so gives those groups what scholar Whitney Phillips has called the “oxygen of amplification.” During the pandemic, journalists have often engaged in what Claire Wardle of First Draft News calls “chasing the pre-print.” They have written up studies before they have gone into peer review, often undermining their readers’ trust because those studies later prove not to have such sensational results.

Well-meaning journalists can do better and they generally want to. But they are often harried by deadlines and facing increasing pressure, as traditional media outlets suffer huge drops in advertising revenue and mounting job losses. The erosion of local journalism is particularly concerning. New funding and revenue models are desperately needed. These are already old discussions, but they remain vital for the health of any media ecosystem.

Just like systemic understandings of viruses remain fundamental to our response to COVID-19, a systemic understanding of the platform ecosystem — and how it interacts with the offline world — remains fundamental to address our problems of platform governance.

Yet, in some countries, there are newspapers, television news channels and radio shows that are deliberately undermining the possibility of a shared reality around COVID-19 public health guidelines. One recent study explored the impact of TV on behaviour around COVID-19 in the US by unpicking the behaviour by viewers of two Fox News shows — Hannity and Tucker Carlson Tonight. While Carlson warned about the threat of COVID-19 starting in early February, Hannity downplayed the virus until mid-March. Places with more Hannity viewers had more COVID-19 cases and deaths. Given that Fox News has downplayed the virus overall, effects are likely even stronger on its viewers compared to those on users of other media outlets.

More traditional media have possibly exerted a greater effect on many in the United States than social media. In their 2018 book Network Propaganda: Manipulation, Disinformation, and Radicalization in American Politics, Yochai Benkler, Robert Faris and Hal Roberts found that Fox News and Donald Trump himself spread far more false beliefs than Russian agents or Facebook clickbaiters from 2015 to 2018. This dynamic has only intensified in 2020. Most recently, President Trump claimed that mail-in votes would be fraudulent, and cited that as a reason why he may not accept the election results next month. Without addressing political polarization, there can be no United States of healthy conversations.

Government Communications

The United States is an extreme example. Just like COVID-19, the infodemic has hit different places with different intensities. While there is still much to learn about why particular approaches worked, rapid and responsive government policy proved essential to address both epidemics.

There are reasons why misinformation has proven less of a problem in places like South Korea, Senegal, or New Zealand that have also largely controlled the pandemic. A few weeks ago, I co-authored a report with Ian Beacock and Eseohe Ojo that examined public health communications in nine democracies around the world. Compared to countries such as the United States and the United Kingdom, other jurisdictions took public health communications and adapted them to the particular contexts of their populations. We used our in-depth study of these nine countries to develop the five RAPID principles of effective democratic health communications (rely on autonomy, not orders; attend to values, emotions and stories; pull in citizens and civil society; institutionalize communications; and describe it democratically).

The acronym was not chosen by chance: a big-data study in the Journal of Medical Internet Research during the first 100 days of COVID-19 in 12 countries concluded that “the public is highly responsive to governmental risk communication during epidemics.” The study showed that when governments informed their populations swiftly with clear public health guidelines, there were fewer online searches for and purchases of questionable treatments.

Without delving into detail here, we found that governments and health officials’ provision of clear, compassionate, consistent and contextual communications dovetailed with better COVID-19 outcomes, as measured by the country’s own understanding of success. The great communicators of science and risk incorporated emotions and societal values, showed compassion and empathy, explained uncertainty, and pulled in citizens and civil society, all of which made messages more credible and wide-reaching. These strategies and others are not rocket science, but when executed well, they were highly effective. In contrast to citizens’ experience with messaging in, for example, the United Kingdom — using the same social media networks — citizens in New Zealand knew that Jacinda Ardern’s Facebook Live appearances were the place to find reliable information.

Governments need to step up to provide transparent, clear and trustworthy information. And politicians need to decide when it is time to engage in politics as usual and when it is not. In Canada, British Columbia’s response was so effective in part because the opposition party (the Liberals) supported public health officials and the BC government’s approach. Other governments have built trust by admitting mistakes: Norwegian Prime Minister Erna Solberg talked this summer about her regret at such a strict lockdown, which she in hindsight saw as too stringent. Others have found balances of privacy that work for them; South Korea is creating technologically savvy systems to show the location of cases, while Taiwan’s Digital Minister Audrey Tang built a real-time map showing the number of masks available to purchase from pharmacies during the early months of the pandemic.

If, however, politicians and public health officials cannot provide clear, basic information, how can they expect their citizens to keep listening? Early in October, four politicians and public health officials in Ontario took three minutes to answer a question about how many people could gather for the Canadian Thanksgiving long weekend. I watched that clip, and afterwards I had no idea what I would have to do if I were living in Ontario.

Officials also need to make themselves trustworthy by following their own rules. In the United Kingdom, Dominic Cummings, chief adviser to the prime minister, broke lockdown rules and faced no consequences. A study in The Lancet found that this action weakened public faith in the government’s COVID-19 response.

Political, Social and Economic Problems

One Health reminds us that we will not stop the emergence of other novel pathogens if we do not attend to broader problems such as climate change that may seem unrelated to COVID-19 at first glance. But climate change has laid the foundations for novel pathogens to emerge, as animals and people flee previously habitable environments. So, too, if governments do not address the broader social and economic determinants, will online conspiracy theories and rejections of public health guidelines continue and accelerate.

It’s clear that the more problematic parts of the online world do not have equal purchase for all people and in all countries. There are many extra-platform reasons why conspiracy theories have taken hold. In the polarized United States, the pandemic has accelerated already disturbing trends: In 2017, only eight percent of Democrats and eight percent of Republicans believed in using violence to advance political goals. By December 2019, these percentages had already doubled to 16 and 15 percent, respectively. By September 2020, the numbers believing this had grown to 33 percent of Democrats and 36 percent of Republicans. When violence has become accepted as an appropriate response, an online rumour can spark offline crimes far more swiftly.

Since COVID-19 became pandemic in March, the conspiracy theory QAnon has attracted a massive growth in followers. Why such growth and who is susceptible? Just as some people and groups are more susceptible to catching COVID-19 or to suffering worse consequences, so too will some people be more likely to trust in online conspiracies. There are social determinants of conspiracy theory adherence, just as there are social determinants of health.

These social determinants can stem from distrust of institutions, resentment of elites, racism and many other factors. That distrust and resentment in turn do not spring from nowhere; they often intertwine with rising inequality and frustration at poor job opportunities. Intertwined with the social factors, then, are economic causes.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic emerged from a novel pathogen. But it was “an expected global health concern,” as several infectious disease specialists put it in March. While no one could have predicted the exact timing and trajectory of COVID-19, many public health experts have long been raising the alarm about zoonotic diseases and their capacity to spread rapidly around the world. The concept of One Health offers one way to explain why these new diseases did not appear out of nowhere but rather emerged from certain humans’ disregard for animals, plants and our planet. It was not a question of if, but when. Only by addressing the systemic problems highlighted by One Health can the world start to prevent the emergence of such novel pathogens rather than continuing to deal with every spread ad hoc.

We can think about the online world through the lens of One Health too, and move beyond addressing each outbreak online, whether it’s genocidal hate speech in Myanmar or Ethiopia, or misinformation about COVID-19 in North America. We only get so far if we take each pandemic at a time. Renée DiResta of the Stanford Internet Observatory has observed that “in every outbreak throughout the existence of social media, from Zika to Ebola, conspiratorial communities immediately spread their content about how it’s all caused by some government or pharmaceutical company or Bill Gates.” COVID-19 has been no exception, with an accelerated barrage of (often anti-Semitic or racist) falsehoods flying around social media and private messaging apps.

The idea of One Health encourages us to take a more holistic approach. It offers a language from the health sciences to talk about platform governance. It reminds governments that they also must take responsibility for producing high-quality, transparent and reliable information for their citizens. It focuses our attention once more on the factors in the offline world that attract particular people to hate and conspiracy theories online. And it reminds us that an epidemic in one place travels swiftly to another. Despite talk of a deglobalizing world offline or the splintering of the internet online, we nonetheless live in a hyperconnected society. A One Health approach to platform governance takes our connections seriously and reminds us that no user can be healthy online until we create systemic change.