Southeast Asia is a hub of not only disinformation innovations but also bad examples of disinformation regulation. Between autocratic governments using “fake news” panics to seize more political control, an entrepreneurial and unregulated digital workforce, and tech platforms with uneven procedures of engaging with state actors and civil society, the region poses challenging questions for disinformation researchers and policy experts.

How can disinformation interventions be better focused on shedding light on the underlying structures and shadowy strategists rather than going after visible targets or the latest fads in fake news? What are the risks to personal and social freedoms posed by new regulations securitizing anti-fake news initiatives that consolidate more power to state and military? What are some support mechanisms that academics, journalists and activists can establish to help each other, especially in moments of state harassment or online trolling?

Penalties for sharing or even “liking” defamatory content or for “spreading false information” intensify the chilling effects of a repressive regime.

Earlier this year, my colleague Ross Tapsell and I released a report outlining lessons from recent electoral experiences in three Southeast Asian countries. We discussed how Southeast Asia serves as a cautionary tale for other countries when fears of fake news are hijacked by state leaders to expand their surveillance of digital environments and to chill free speech. In the pandemic moment, fake news, moral panics and fears of the virus have converged, and at least 16 world governments from Romania to Botswana have emulated examples of “overreaching” social media laws and scare tactics first seen in Singapore and Malaysia. What can Southeast Asian experiences in the fight against fake news portend for the rest of the world? Our research points to three key findings.

Social Media Regulations Tilt the Political Battlefield for the Incumbents

The most recent Southeast Asian elections in Indonesia, the Philippines, Singapore and Thailand saw incumbents winning the high-level races. While incumbents strategically used the state’s information machinery to shape mainstream and social media narratives in the elections, they also harnessed both election campaign regulation and social media content monitoring to their advantage. For instance, Indonesia’s election-related police arrests were highly politicized, with arrests made only against those who created “hoax news” against incumbent President Joko Widodo. In Thailand, opposition figures were admonished for uploading false information in social media and, in other cases, disqualified for violating election law or prevented from grassroots campaigning. Penalties for sharing or even “liking” defamatory content or for “spreading false information” intensify the chilling effects of a repressive regime.

As social media becomes more central in political campaigning, especially in the pandemic moment, we should be alert to how politicians may use fears of the “infodemic” to introduce regulations with vaguely phrased definitions of fake news. Such government regulations deepen cultures of self-censorship, facilitate a growing lack of trust in politicians, reduce transparency in governance, inhibit dissent and exacerbate long-existing inequalities in political participation.

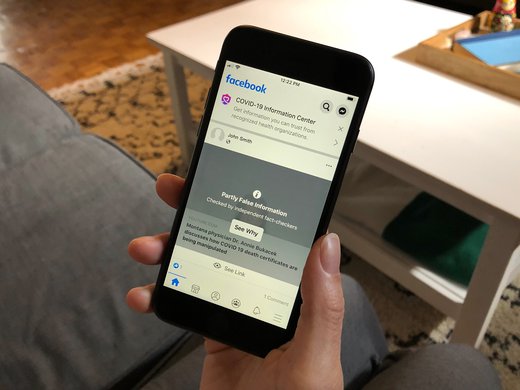

Blaming Facebook Is Easier for Everyone than Seeking Local Reform

Platform determinist narratives assign primary blame to Facebook for the crass tenor of partisan debate and for “surprise” electoral outcomes. It’s undoubtedly important that we should keep applying pressure to platforms to improve their content moderation of hate speech and to enhance the support for the many precariously employed content moderators in the region. It’s also urgent that we demand better representation of the region in the Facebook Oversight Board, which is responsible for reviewing content takedown decisions. As legal scholars argue, it’s disproportional that only one Southeast Asian representative is on the 20-person board when global surveys have identified that four of the top 10 countries with the most active users in social media are in Southeast Asia.

However, researchers, activists and policy experts should resist adopting a securitization framework and platform determinist approaches in their own advocacies and should support instead bottom-up interventions that aim for transparency and fairness in political exchange on social media. Election integrity initiatives that can spotlight the accountability (or complicity) of a broad range of public relations firms, political consultants and influencer marketing agencies in ever-expanding shadow economies require the messy hard work of bridge-building. These efforts should also resist applying simplistic good-versus-evil or post-by-post takedown frameworks to social media content moderation.

The existence of many clickbait websites, Instagram click farms, and dark public relations firms in the region suggests that advertising and promotional infrastructures have made fake news production financially rewarding. Researchers and civil society in the region have not adequately engaged with these infrastructural issues that speak to why disinformation production has been so innovative. Focusing on personality-oriented reporting or the unmasking of lower-level “trolls” can only expose individual targets and does not address root causes.

What Happens When Opposition Figures and Activists “Fight Fire with Fire”?

We should be careful to ensure that this urgent fight against fake news doesn’t turn us or our allies into the very enemies we vow to fight against. One of the findings in our Southeast Asian elections study is that disinformation became “democratized,” and that politicians and their supporters who previously decried disinformation campaigning adopted some of these same tactics to try to fight fire with fire. While some coordinative tactics are productively disruptive of racist speech — for example, K-pop fans’ recent torpedoing of racist hashtags against the Black Lives Matter movement — we should be cautious that some other tactics might reproduce vicious cycles of hateful confrontation.

Even Singapore, with its tradition of restraint and civility in political debate, witnessed an escalation in dirty campaigning from politicians across the political spectrum, and academics sympathetic with the beleaguered opposition party had to call out their own colleagues for behaving like bullies. In the Philippines, opposition politicians and online influencers were occasionally complicit with the surge of anti-China racist speech and conspiracy theory in the wake of COVID-19. Rather than fact-checking their statements or calling these people out, some journalists reproduced this hateful rhetoric in their own personal pages or republished conspiracy theory in national newspapers.

Researchers and policy experts thus have an important, yet challenging, responsibility to take a step back and challenge the good-versus-evil frames that only deepen the many ethnic, racial, religious and class divides in Southeast Asian contexts. We need to be ever mindful and critically collaborative, and must ensure that our efforts to fight fake news are not for nothing. We need regulatory measures that are neither easily co-opted by repressive power structures nor complicit with elite or partisan interests that may be seeking to impose singular perspectives rather than to expand debate and invite greater participation.