How we govern digital technologies, and in particular global platform companies such as Facebook, Google and Amazon, is one of the defining policy challenges of our time. This is so not only because the potential harms of getting it wrong are so clear and we need to protect the potential for economic innovation and political empowerment, but also because we must now view tech governance as a geopolitical wedge.

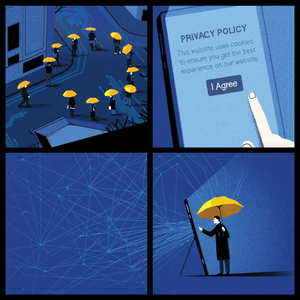

The world is splintering in three tech governance blocks: a Chinese state-centric model, where a truly massive, centralized data set is used as a tool of economic and political control; an American private sector model, where the (largely) United States-based tech platforms are given free rein, absent regulatory constraint; and an emerging European Union-led rights-focused regime, which has long promised to put the protection of individual rights at the centre of legal and regulatory systems.

This divided governance landscape appeared in stark relief when Facebook’s chief executive Mark Zuckerberg made a visit to Brussels last week — and in state-visit fashion. Meeting with EU commissioners days before launching a Facebook white paper on tech regulation called Charting the Way Forward: Online Content Regulation, Zuckerberg mapped out Facebook’s vision for a globally coordinated regulatory approach. Facebook has more than 2.5 billion monthly active users, hosts 100 billion new pieces of content a day and operates in most countries. The challenge they face is that regulations on speech are deeply historical and national, and governed by nation-states. Germany’s laws around pro-Nazi speech, for example, are very different from Canada’s. But Facebook’s need for global rules and the ways in the past we have governed speech (not to mention data laws and competition policy), are increasingly at loggerheads. At their core, questions about content regulation are about governance.

It’s safe to say that Zuckerberg received a cold reception in Brussels. “It’s not for us to adapt to those companies,” remarked European Commissioner for Internal Market Thierry Breton, “but for them to adapt to us.”

Later in the week, through a series of announcements on technology policy, the European Union spelled out what that adaptation might look like.

Up until now, the European model was largely grounded in the implementation of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) in the European Union, and a range of regulatory experimentation at the national level (such as Germany’s “NetzDG” law governing hate speech and other illegal content online). But a more comprehensive strategy for this regulatory approach to governing tech has been in discussion for years, and we may have just caught a glimpse of its future — the European Commission announced its long-awaited grand strategy for taking on US tech companies. The strategy is a governance agenda centred on two components of the digital economy: first, the data collected about EU citizens, and second, the tools built on top of these data, namely, artificial intelligence (AI).

The data strategy aims to create an EU data pool sitting on servers within EU jurisdiction (to allow for the enforcement of EU data protections). The data would be made available to EU firms, and large global platforms operating in the EU market would be forced to contribute data.

How this data pool can be used is the subject of an AI white paper, released at the same time.

The proposed AI strategy deviates significantly from the free rein given to American and Chinese tech companies regarding AI development. Instead, it puts individual rights at its core. The white paper proposes rules: to ensure the more accurate representation of data used in the development of AI; to ensure that high-risk tools are not being built on biased data; to set guidelines for the explainability of AI systems so that regulators are able to better understand potential problems and companies can be held accountable for decisions made based on their systems; to require strict notifications for citizens when decisions about them are being made by AI; and to address demands for greater human oversight of these systems. The proposal also makes a distinction between high-risk (such as health care and policing) and low-risk AI applications, setting stronger protections on the former while enabling the development of the latter.

These two documents are linked together in a third, a broader strategic road map, entitled “Shaping Europe’s digital future.” In this, the European Union proposes a wider set of policy ambitions, including competition policy and the use of technology to achieve climate change objectives.

Mark Scott, the chief technology correspondent at POLITICO (whom we talk to in this week’s episode of Big Tech), argues that these three documents offer a striking look into the European Union's political ambitions and its plan for big tech. First, there is not yet consensus among EU commissioners. Whereas Margrethe Vestager, executive vice president of the European Commission for a Europe Fit for the Digital Age, sees tech regulation as enabling individual rights and market-driven innovation, Breton has a much more protectionist vision on market regulation. Second, this is clearly a geopolitical play by the European Union. European tech companies have been left behind Chinese and American competition, and the hope is that a new protected data space and set of guardrails could incentivize the development of a set of technologies better aligned with democratic values. Finally, according to Scott, it is entirely unclear whether the European Union can pull this off. While the European Union sets regional policy, member countries are experimenting with their own agendas in this space. With EU countries representing a range of democratic systems, the scope of policies implemented will be diverse and possibly in deep conflict with one another (for example, on issues such as free speech). What is certain is that this experiment will be of keen interest to the countries around the world (Canada included) that may be looking for new frameworks with which to govern digital technology.