Many of the dispatches from this year’s World Economic Forum (WEF) read like ghost stories; the panel discussions, parties and private chats were haunted by the spirits of the absent.

Tim Cook, the chief executive of Apple Inc., attended the annual gathering of the global elite in Davos, Switzerland, for the first time. But if he was planning facetime with the presidents and prime ministers of his company’s most important markets, he picked the wrong moment to make his debut: the leaders of the United States, China, France, the United Kingdom, India and Canada all stayed away.

In a newsletter, The Wall Street Journal’s Greg Ip wrote that even though Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell was in Washington preparing for the US central bank’s next policy meeting, “his presence was everywhere.” Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, the Democratic congresswoman and social-media sensation who wants to raise income tax rates to 70 percent for the richest Americans, wasn’t in the Swiss Alps either, but “it felt like she was,” Andrew Ross Sorkin, a columnist for The New York Times, told the readers of his DealBook tip sheet.

“Davos Man,” it seems, has been reduced to a shell of his former self; the modern era of globalization is in crisis, and the global super elite have nothing new to offer. Sorkin, known for his access to Wall Street’s power brokers, reported that the Davos attendees were passing around a letter that billionaire investor Seth Klarman had written to his clients, in which Klarman despairs that “it can’t be business as usual amid constant protests, riots, shutdowns and escalating social tensions.”

No doubt connections were made that will lead to an investment here, a charitable initiative there, and maybe even a policy tweak at some point in the future. But as a group, the people who pay tens of thousands of dollars to attend the WEF’s premier event have never looked more lost than they did in 2019. Politics has shifted away from the centrist consensus that brought several decades of economic stability but also extreme levels of income inequality, alarmingly rapid climate change and a technological revolution that has benefited a few and destabilized many.

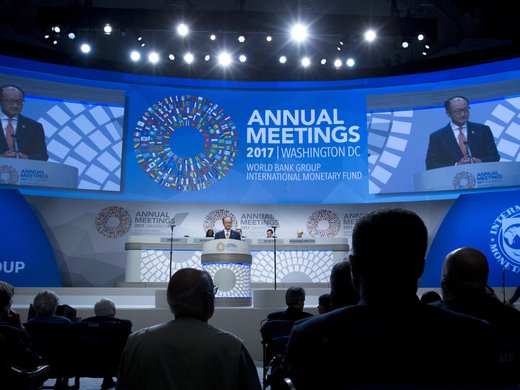

The global elite have been talking about these things for years at places like Davos and in the communiqués issued by the Group of Twenty (G20) and the International Monetary Fund (IMF). Yet little, if anything, changed. Now, the postwar order, as we knew it, is “all but dead,” Axios declared in its summation of the latest WEF conclave. The vacuum created by the election of Donald Trump as US president remains, and no one knows who might fill it. Some wonder if anyone will.

“There is a gaping absence of leadership in Davos from the usual defenders of liberal democracy and the rules-based international system,” Fareed Zakaria, the broadcaster and writer, said in his Washington Post column on January 24. Zakaria, a respected voice on international affairs, later asked, “In a world without leaders, will that system over time weaken and eventually crumble?”

No doubt, things look grim. In a January 28 speech in Singapore, Christopher Pine, Australia’s defence minister, implored the United States and China to avoid dividing Asia into “Cold War-like blocs.” The fact that a senior minister from a G20 country felt compelled to take such a stand says a lot about the state of the world in 2019. The world’s two greatest powers have chosen to confront globalization on their own terms. The multilateral system will suffer.

Yet, it is wrong to say there are no leaders fighting for the global norms conceived at Bretton Woods, New Hampshire, near the end of the World War II; a few are trying. While this handful of leaders won’t be able to reproduce the relative economic stability of the 1990s and most of the first decade of the current millennium — at that time, the United States was still committed to expanding the liberal order, and China was focused primarily on generating economic growth — they might be able to make incremental gains, especially if others join.

Japan’s Shinzo Abe salvaged the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) after it was abandoned by Trump, ensuring the trade pact took effect at the end of 2018, after the legislatures of six countries — the minimum for ratification — passed law enshrining the terms of the pact.

The European Union has implemented internet privacy rules and fined technology behemoths for abusing their market power — carrying out actual policy responses to issues that most have expressed concern about, but few have found the resolve to address.

Chrystia Freeland, Canada’s global affairs minister, has been urging smaller free-trading democracies to lead as a group if Washington isn’t willing to light the way. Canada hosted a collection of like-minded trading nations in Ottawa in October to discuss overhauling the Word Trade Organization (WTO), purposely excluding antagonistic countries such as the United States, China and India. Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s government joined the Lima Group of Latin American countries to push for the return of democracy in Venezuela. The Canadian Press reported that diplomats from Canada and other Lima countries lobbied the Venezuelan opposition to unite around Juan Guaidó, allowing the United States and most of the rest of the Western Hemisphere to recognize him as Venezuela’s leader.

These examples suggest that Trump’s disregard for the international order is being regarded by some nations as a rare opportunity. When someone from Washington is in the room, that person sets the tone. But if the United States is uninterested, then smaller countries get to set the terms, and even to realize new gains. The Canada West Foundation, a think tank, found that Canada would do better in an Asian trade agreement that excluded the United States, because Canadian farmers would get a jump on their American rivals. Freer trade involving the world’s biggest economy obviously would have the greatest net benefit, but its removal from the equation doesn’t make the result zero.

However, for this approach to global leadership to work, the participants have to produce a steady stream of tangible results. So far, they haven’t.

The G20 promised in 2014 to work together to expand its collective GDP by two percent in four years. The pledge was a gimmick; it got nowhere close. If citizens don’t feel as if quality of life is improving, they are likely to give up on free trade and global cooperation. Recent elections suggest that some citizens already have given up.

The countries that say they care about the current international order must act on the long list of global issues that they have debated for years but have done nothing to resolve. The group that met in Ottawa to repair the WTO must finish the job. The oversupply of steel, which the G20 pledged to resolve, would be another obvious target, as would the rampant abuse of international tax law. And if the Davos attendees fear income tax rates of 70 percent, they will cooperate with policy makers on a middle ground.

The greatest challenge for the leaders working to maintain the international order sits at the centre of the Bretton Woods system itself — the IMF and the World Bank.

Angela Merkel, Germany’s chancellor, said in Davos that the IMF and the World Bank should be reformed. She’s right. The institutions were designed so that control would rest with Washington and the major capitals of Europe. For at least a couple of decades, leaders from those places have agreed that the system no longer reflects the state of the global economy. Yet, again, they have done almost nothing to change the system.

The absence of political star power at Davos was bad news for the organizers. It will be good news if it means leaders have figured out that the time for talking has passed. The only thing that will keep the liberal order from crumbling is some hard evidence that it still works.