This May, parliamentarians from 10 countries travelled to Ottawa to participate in the International Grand Committee on Big Data, Privacy and Democracy, a multilateral effort aimed at increasing global collaboration in the area of digital regulation.

The three-day meeting was hosted by the Canadian House of Commons’ Standing Committee on Access to Information, Privacy and Ethics, and testimony was provided by representatives from technology giants Facebook, Google, Twitter, Microsoft and Amazon, as well as academics, business leaders and others (including Jim Balsillie, CIGI co-founder and chair of the board and Taylor Owen, a senior fellow at CIGI).

This effort is reflective of a trend that sees Canada more involved in the international dialogue surrounding the regulation of social media companies, in part due to heightened concerns over foreign election interference and the negative impact of disinformation on democratic processes. “We thought [it] better [to come] together as a coalition of countries to work out some solutions to these problems,” said Bob Zimmer, chair of the standing committee, to the crowded room on the first day.

Increasingly, Canadian politicians recognize that multilateral collaboration is needed to tackle the challenges posed by technology companies, and social media firms in particular. But can an international approach overcome the existing challenges to social media regulation? And what limitations does it pose, especially for Canada?

The Multilateral Approach

While multilateral cooperation on social media regulation may be newer territory for Canada, it’s been a routine element of other countries’ policy development processes for some time.

In recent years, for example, EU member states have worked together to address policy issues with substantial implications for the operations of these companies, including privacy and copyright — amongst others. In several cases, this dialogue has led to the development of legislation and, in a number of instances, the European Commission has investigated and finedsocial media companies found in violation of EU laws.

Other collaborations were prompted by crises. Only a few weeks prior to the International Grand Committee meetings in Ottawa, New Zealand’s prime minister, Jacinda Ardern, and France’s president, Emmanuel Macron, co-hosted a Paris summit organized in response to the livestream of a terrorist attack in Christchurch, New Zealand on Facebook.

Referred to as the Christchurch Call, the gathering aimed to “bring together countries and tech companies in an attempt to bring to an end the ability to use social media to organise and promote terrorism and violent extremism.” As part of the effort, eight tech giants, including Facebook and Twitter, the European Commission and 17 nations, amongst them Canada, signed a voluntary call to action in support of the goal.

Various intergovernmental organizations have also proposed recommendations related to social media governance in recent years. Last year, the UN released a report advocating for a human rights approach to platform content regulation. More recently, UNESCO called for the modernization of electoral regulatory frameworks to reduce the spread of disinformation on these platforms. Both the UN and the OECD have been flagged for potential roles in the development of global rules for companies like Facebook.

Canada's Involvement

Neither the three-day meeting in Ottawa this spring nor the Christchurch Call were Canada’s first time taking part in substantial multilateral efforts to discuss the regulation of social media companies, however.

Three members of Canada’s Standing Committee on Access to Information, Privacy and Ethics participated in the inaugural meeting of the International Grand Committee last fall in London. The summit was part of the UK’s Digital, Culture, Media and Sport Committee’s inquiry into disinformation and fake news. It bears many similarities to the more recent gathering in Canada’s capital.

For one, both forums saw participation from a range of diverse countries. In London, alongside members of the UK committee and the three Canadian MPs, parliamentarians from Argentina, Belgium, Brazil, France, Ireland, Latvia and Singapore were present. Later in Ottawa, government representatives from Costa Rica, Ecuador, Estonia, Germany, Ireland, Mexico, Morocco, Singapore, St. Lucia and the UK sat alongside members of the Canadian standing committee.

Respective witnesses from a variety of backgrounds, including regulators and industry representatives, were present. And joint declarations were signed by parliamentarians that highlight the “signatories’ commitment to transparency, accountability and democracy” in the “regulation of technology platforms.”

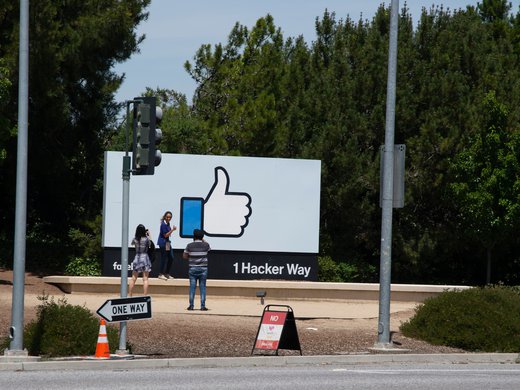

Yet, there is another parallel that should not go unnoticed. The most pertinent witness asked to appear didn’t bother to show up either time: Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg. Indeed, Zuckerberg and Facebook COO Sheryl Sandberg ignored summons to testify in Ottawa. (Global policy directors, Kevin Chan and Neil Potts, represented the company instead.) The committee has since passed a motion to call the executives as witnesses the next time they enter the country.

Challenges: Reining in Companies and Navigating Diverging Regulations

Zuckerberg’s empty chair is emblematic of one of the existing challenges to social media governance, and it’s one that doesn’t appear to be mitigated by increased international cooperation.

The quandary is how to regulate global companies that do not consistently answer to the governments of the countries within which they operate. Certainly, the readiness of Zuckerberg to ignore calls from administrations, which in the most recent meeting represented more than a combined 402 million citizens, is a highly public snub. It suggests that the CEO remains unconvinced that his absence may have negative implications for Facebook’s business operations, despite the breadth of countries demanding his participation.

Another difficulty, and one specifically prompted by increased collaboration in the area of social media regulation, is how parliamentarians should negotiate the diverging regulatory outcomes sought by participating countries. Despite many common beliefs and norms, Canada’s situation is different than those of its counterparts on the International Grand Committee. What Canadian parliamentarians understand to be transparent, accountable and democratic social media regulation will vary in some ways from other governments’ representatives.

Heidi Tworek, assistant professor of international history at the University of British Colombia, convincingly argues, for instance, that “it is hard to imagine [intergovernmental] agreement over [online] content standards between democracies, let alone between authoritarian states and democracies.” This suggestion resonates with other Canadian academics who point to significant flaws in Australia’s recent legislation related to the distribution of violent extremist content online. Viewpoints can and should be taken from other countries’ approaches, but Canadian legislation must reflect Canadians’ shared values and the country’s unique social, political and economic systems.

Finally, collaboration in this area has resulted in new intergovernmental working practices and relationships. The International Grand Committee has brought together many politicians whose work otherwise largely centres on domestic issues and involves local colleagues. Accordingly, when needed, guidance and support for Canadian parliamentarians new to working across borders and cultures should be made available.

Looking to the Future

None of this is to say that collaborative approaches to social media regulation do not show promise for strong and robust policy. To the contrary, this cooperation illustrates the willingness of Canadian and foreign parliamentarians to address the challenges posed by social media giants with due gravity and put aside partisan, geopolitical and other considerations. Moreover, it demonstrates the possibilities of an interconnected regulatory framework for policy issues that are themselves uniquely global in reach and scope.

Rather, the point is that proper steps should be taken to ensure that these efforts are effective, meaningful and reflective of Canada’s place within this larger international context. Further, it is a caution that while multilateral engagement may be a step in the right direction, certain social media executives often remain unwilling to come to the table.

To make that happen, stronger measures might need to be taken, including securing participation from US parliamentarians in the International Grand Committee. Not least because Facebook is headquartered in Silicon Valley and Zuckerberg has previously testified before a US congressional committee, but such a step may force the CEO’s involvement. And indeed, given the lack of transparency around the business operations of Facebook and other social media companies, such cooperation is a critical component of informed regulation in this area.

The third meeting of the International Grand Committee will be held in Dublin this November. This will be another opportunity for Canadian parliamentarians to show their grip on the issues at hand and their capacity to work across the aisle and across borders. And lessons learned from the upcoming Canadian federal election, which has prompted the government to take a range of steps aimed at safeguarding the vote from online foreign interference, should come in tow. As to whether Mark Zuckerberg will be there — well, we’ll see.

This article first appeared on OpenCanada.org.