For thousands of years at least, humans have wondered about the skies above them and created mythologies and theories about outer space. While telescopes enabled a major advancement in our understanding, a revolution occurred when humans were able to establish artificial satellites orbiting the Earth in the late 1950s. Since then, different forms of space and technology races between nation-states have ensued, some leading to significant international cooperation (such as the International Space Station) and others to international tensions and technological failure (such as the “Star Wars” defence system).

Today, we are likely on the verge of a new phase, fuelled by the growing activities of the private sector, as well as by competing security and economic interests, combined with advances in technology. For example, we are witnessing the emergence of new “mega-constellations” of satellites and the testing of anti-satellite (ASAT) missiles. The devastatingly effective use of satellite-based technologies by Ukrainian forces against their Russian attackers is clear evidence of the power of this technology in warfare; the lesson has been well noted.

Space governance is now clearly part of core geopolitical strategy, and not only for the largest spacefaring nations. The company SpaceX has helped ignite an age of private sector activity. Many companies are now pursuing commercial interests through space-based communications, and the emerging role and impact of these companies highlight some of the governance challenges and trends explored in this essay series.

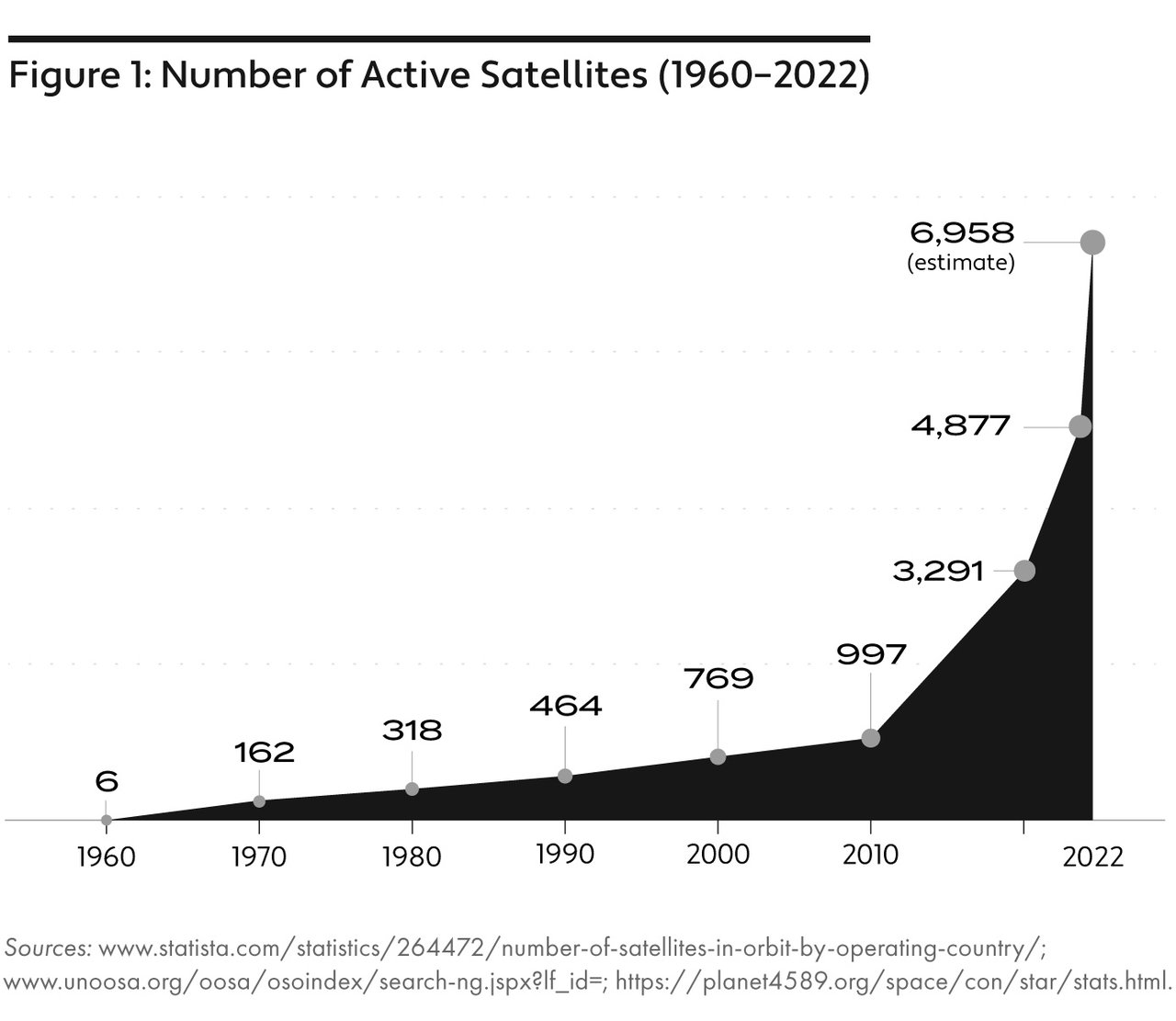

Figure 1 below underlines the significant material change that Elon Musk’s satellite-based internet service, Starlink, and other private companies have brought to space. By the end of 2022, it was estimated that Starlink alone had more than 3,300 small satellites in orbit, almost half of the total. The number of satellites is projected to continue to grow quickly, involving an increasing number of players and creating new risks.

As the number of active satellites grows, so too does human reliance on those systems. We use them for communication, navigation and Earth observation. But nestled within this space infrastructure are use cases that, in many ways, make modern life possible, including the synchronization of financial transactions, transportation, weather forecasting, smartphones and entertainment, among others. This web of satellite-based applications links to issues of data governance: who has access to what data, and who controls its use. Satellites will increasingly be a key part of the world’s data infrastructure.

These trends will put pressure on an existing governance architecture that is weak, piecemeal and no longer fit for purpose. In the emerging structure, the players are different, the volume is different and the use cases are different. These pressures create risks for a classic tragedy-of-the-commons scenario, where individual companies or nations-states prioritize short-term self-interest over long-term stability. A commons failure could take many forms, including the launch of ASAT missiles, the creation of large debris fields or the use of cyberweapons. Building a framework that strives for a more equitable distribution of resources between developed and developing countries will be a critical challenge.

The time to focus on space governance has arrived. If the world makes progress on governance, future generations will achieve greater benefits from the human ingenuity and innovation that are under way. The ideas contained within this series are a step in the right direction.