More than 60 speakers from all corners of the globe took part in 6 Degrees, a three-day forum on inclusion run by the Institute for Canadian Citizenship, including Canadian writer Cory Doctorow, French YouTuber Aude Favre, Anishinaabe comedian Ryan McMahon, Pussy Riot co-founder Nadya Tolokonnikova, The New Yorker’s Adam Gopnik, and many more.

OpenCanada is a digital media partner of 6 Degrees, as it has been the last few years. As a result, in 2018, a number of speakers discussed the changing concept of citizenship on our site and OpenCanada led an online discussion between 6 Degrees guests Margaret Atwood and Sue Gardner. In 2017, others put forward examples of barriers that are in need of breaking down and in 2016, we named initiatives that advance pluralism and should be embraced more broadly.

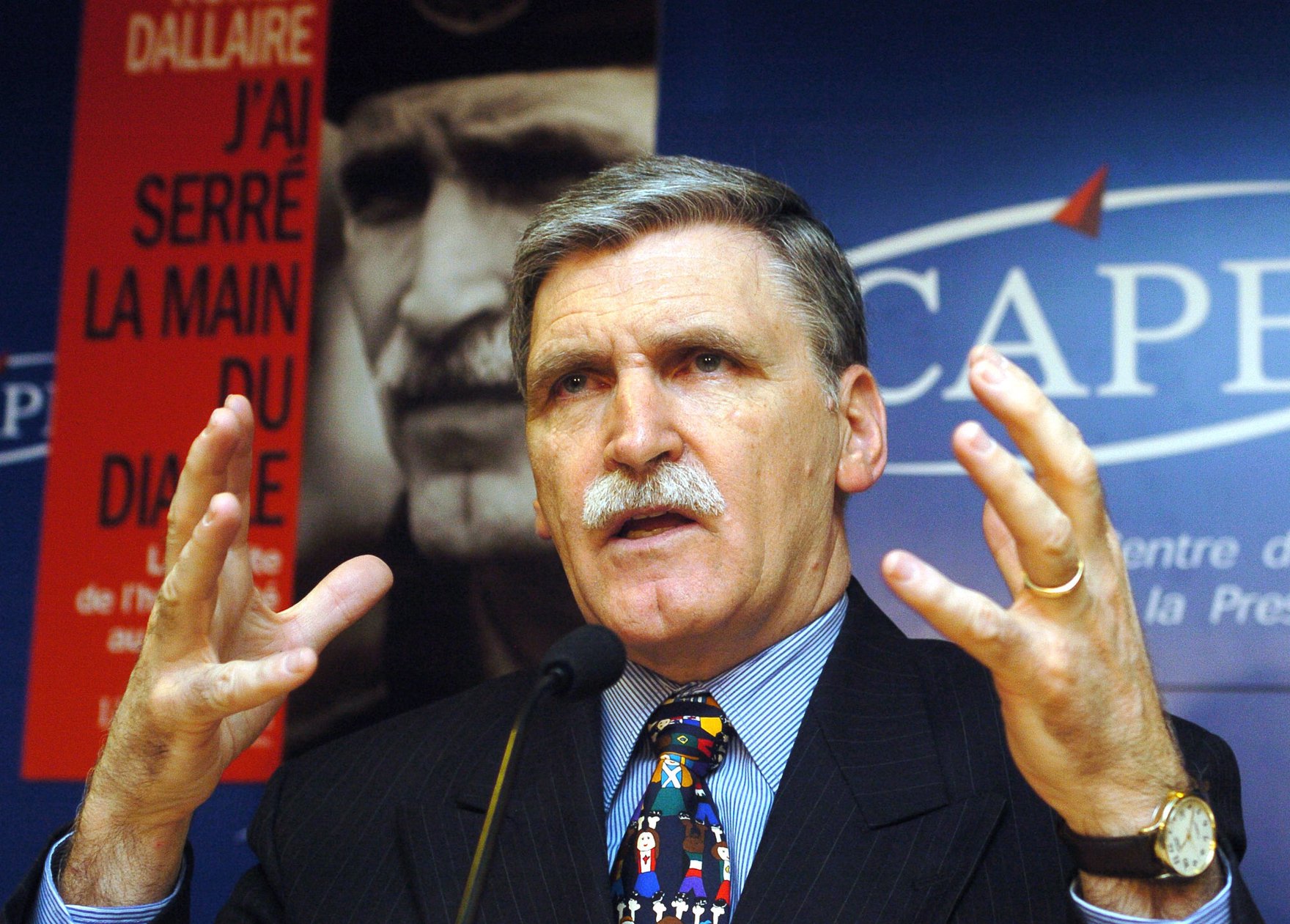

In advance of this year’s forum, which ran from September 23 to 25 in Toronto, OpenCanada spoke with retired Lieutenant-General Roméo Dallaire, who close the week’s events when he received the 2019 Adrienne Clarkson Prize for Global Citizenship Wednesday evening at Koerner Hall.

“The life and career of... Dallaire is an urgently needed reminder of the very real consequences of inaction in the face of growing divisions in Canada and around the world,” the 6 Degrees announcement said.

Dallaire, who was in charge of the UN peacekeeping mission in Rwanda in 1994 during the genocide against the Tutsi, has spoken out in the 25 years since the mission, most prominently on the perils of global inaction and against the use of child soldiers. In 2005, he was appointed to the Senate of Canada and served as Senator until 2014. In 2007, he founded the Romeo Dallaire Child Soldiers Initiative.

1. Considering the prize you’ll receive next week, what does global citizenship mean to you and has your understanding of it changed over time?

Until I went to Africa, essentially I was a Eurocentric person. My mission, my training, all my commitment with the Canadian Forces was to either serve or to fight [there] — in Norway or in Central Germany and Central Europe. I was deployed there. With Africa and the Rwandan experience, two things changed. One, [I had] the realization that Africa is a place where extraordinary people live with a magnificent internal culture that we can't even approach because we're so materialistic here. Two, [I understood] the vulnerability of humanity and of human rights and the overriding concern that people have with self interest, versus a higher plane.

But the real essence of my learning over the years has been one where I've come to realize that the generation under 25 is a whole different animal. Because they all have a communications revolution in their hand, they Skype anybody in the world, they grasp global matters, they grasp humanity in its totality, they can handle an environment at that grander scale much better than what we've been able to do because they are already global with those communications. I see an extraordinary, new generation that is probably going to push us aside if they want to build a global environment, a global sense of humanity, [rather] than the local, national perspectives that we work on.

2. In your journey to promote understanding on a number of different issues, what lessons have you learned about how we speak to those with opposing views?

The older the people are, the more entrenched they are in what they are comfortable with, within their own national boundaries and their own families and their own cultures and their own traditions. When these things clash with international standards — like nobody under the age of 18 should go to war, girls under 18 are not women they are still girls and they should not be married off, and these kinds of things — we've got to put a long-term hat on and we’ve got to conduct an attrition of those who are holding positions that are not conducive to preventing conflict and advancing the state of humanity.

A number of years ago during my therapy and my work, I came to the conclusion that, first, human beings are not Darwinian — they don’t try to destroy each other. They really seek serenity. Second, ultimately it is going to be possible, as we move human rights [forward], as we now [are able to] communicate with all humanity, that maybe in a couple of centuries we will resolve the frictions of our differences without having to slaughter each other. I think we will come to the agreement that we are all equal. That all humans are humans and that ultimately we will be able to respect each other. If we do that then we will be on the right path.

3. Can you tell us about the new Dallaire Centre of Excellence for Peace and Security. What do you hope it accomplishes and how will it build off the work you are already doing with your Child Soldiers Initiative?

This is a magnificent initiative that has taken two years to bring to fruition, with a lot of discussion and debate within the hierarchies of [the departments of] foreign affairs and national defence. The essence of it was to find an instrument that would permit us to in the first instance be able to advance the implementation of the Vancouver Principles, which are the principles of prevention of the use of children as weapons of war.

From there, [the idea is to] build out on the variety of subjects on which [former Minister of Foreign Affairs] Lloyd Axworthy spoke of in the ’80s, which was human security. That means women and their place in the world, and girls’ education. It means being able to stop child trafficking. It means working on child labour and reducing that scenario. It's also going to be touching on how to protect and support societies in the prevention of these conflicts and not simply trying to resolve these conflicts. My next book that will come out in a couple of years is going to reflect a lot of that expanded dimension, beyond and also encompassing the child soldier side.

4. What other policies or initiatives would you like to see Canada take up in the next year or five years?

In 2005, I raised in caucus the question: What do we plan to do to use the year 2017? It was the year of a great culmination — the 150th anniversary of the most stable democracy in the world and the 100th anniversary of when the youth of this nation had crossed the pond, fought, bled, died, and won a battle that moved us from being a colonial cousin to an actual nation state. And what do you plan to give us as guidance beyond 2017, in this very complex and ambiguous world that are finding ourselves in, facing revolutions from environmental to technological and more?

2017 was a bust. I mean, we ate cake and we had a couple things here and there, but it was essentially a bust because the essence of good, profound statesmanship is to push us to our potential and to guide us there. So, I feel incredibly strongly that we’ve got to take that young generation and give it some focus, give it some guidance, beyond our borders, and have them be the thrust of our engagement into the future, as their peers are being abused throughout the world. So how do you create an atmosphere in a country where the youth feel that their ambitions are not purely local but in fact global, coming from a nation that has provided examples of stability, of integrating societies, and of an ability to pursue new ideas to advance humanity?

The second [ask] is: take a leadership role, Canada. With the depth of intellectual strength that we have in the diplomatic corps — which should be rebuilt — or be it in the NGO world, be it in academia, be it in industry. But bring Canada back into the world as a leader and as an entity that can be a reference for others.

Thirdly, our role in the world is far more significant than what we’ve even envisioned. We have to really think hard about how to focus this nation as a global leader in moving [forward] human security, human rights and the environment, and reach our full potential. I mean, we’re being outclassed by Norway. Let’s get serious. We have demonstrated over the last 10, 15 years such an aversion to risk that we have turned into a nation that is very provincial, instead of being our full potential.

[Further, on peacekeeping initiatives], we have been trying to convince people that what the world needs is not 20, 30, 40 battalions out there to conduct massive peacekeeping efforts and so on. What the world needs, what an evolving country needs, is an ability to professionalize. They need the depth that we can provide, the skills, the knowledge and the technology to give them the self assurance that they are professional forces and that they can not only help in resolving conflicts but actually prevent them. We should be having so many people around the world providing input — not only from the military but our police forces and our first responders and our youth. I’m not talking about a peace corps. I am talking about something far more sophisticated and far more deliberate. Assist nations to build their human security and be a reference for that. And that means, yeah, going in some places that may not be totally secure. And yes, it may mean paying, on occasion, with some of the blood of our nation to do that. We’ve paid the blood to protect ourselves, why can’t we realize that there is more to us than simply ourselves and that self-interest is not the dominant thematic of this nation?

5. What does progressive policy mean to you? Do you think there is an ebb and flow of making progress? Where are we within that rhythm?

We are at a point of having to decide whether or not we want to commit to the world or whether we just want to take care of ourselves. Survive the future versus making humanity thrive into the future by a rebuilding of the diplomatic corps, by an engagement by the leadership of this nation into not only multilateral organizations — like the UN and NATO — but also bilaterally and that we deliberately commit to nations to assist them. It’s not up to us to tell [those nations] what to do, it’s up to us to assist with them discovering what they have to do and them being able to implement it.

This interview, which originally ran on OpenCanada.org, has been edited and condensed for clarity.