As always, there is a lot of really awful content on the internet, and some of it is really dangerous. The World Health Organization (WHO) has called this an “infodemic,” which it defines as “an overabundance of information — some accurate and some not — that makes it hard for people to find trustworthy sources and reliable guidance when they need it.” Heidi Larson, head of the Vaccine Confidence Project, said in a 2018 Nature article that “the deluge of conflicting information, misinformation and manipulated information on social media should be recognized as a global public-health threat.” When you are trying to inform billions of people about why and how they should drastically change their behaviour, the quality of information being circulated is critical.

And a lot of what is circulating is really bad. It includes:

- medical misinformation such as bad science, false cures and fake cases;

- ideological content from communities who distrust science and proven measures such as vaccines;

- ads for “cures” or other health and wellness products from profiteers, traffic seekers and phishers;

- conspiracy theories, among them that the COVID-19 virus is a bioweapon or was created in a Chinese or American lab, and that Bill Gates planned the pandemic; and

- harmful speech ranging from racist attacks to neo-Nazis talking about ways to “spread” coronavirus to cause chaos.

All this activity is occurring on social platforms, in private groups and on messaging platforms.

Misinformation about the pandemic has too often flowed from the top. The Chinese government worsened the pandemic by censoring scientists, and leading figures (such as Elon Musk) have used their platforms to spread damaging misinformation. Perhaps most extraordinarily, the president of the United States can’t be relied on to provide accurate information to the public, and is using his daily press briefings to spread dangerous misinformation. This has led prominent journalism scholars and media columnists such as Jay Rosen and Margaret Sullivan to call on the media to stop live-broadcasting Trump’s briefings. It is worth pausing to digest just how extraordinary this moment is.

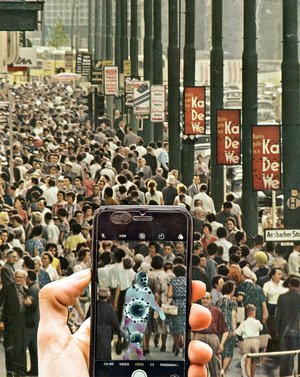

We are experiencing a rare moment in which the entire world needs to know (more or less) the same thing. This situation makes the fragmentation of truths even more worrisome. If we all know different facts about the pandemic, then we will all behave in different ways, precisely at a time that demands coordinated collective action. The public health problem is not any one bad piece of content, but the effect of the sum of the parts. We are being flooded with content, both good and bad, which creates an epistemological problem: how do we come to know what we know?

The platform companies seem to recognize the urgency of this problem and are responding aggressively. Content moderation is always about a values trade-off: the freedom to speak versus the right to be protected from the harms that speech can cause. This trade-off is changing in real time. Just a month ago, platforms were still (to varying degrees) prioritizing the value of frictionless speech over the potential harms of this speech. But now, Facebook, YouTube and Twitter have all taken far more aggressive stances to content moderation on this issue than on, for example, political content. They are so clearly breaking from their previously held positions on content moderation and harmful speech that a lasting legacy of the pandemic could be a larger shift in the content moderation — and the platform governance — debate. The Overton window is shifting.

Platforms are taking more responsibility for content, which does not mean that self regulation is sufficient. It instead shows that citizens and governments can (and should) be demanding more responsibility from them. But what does this look like? Is it sufficient to simply fact-check and pull down more content? Or do we need to think more broadly about the structural causes and solutions to the challenge of harmful content?

Misinformation has never been a problem of individual bad actors. It has, instead, always been a structural problem. It is about the design of our digital infrastructure — the scale of platform activity (a billion posts a day on Facebook); the role of artificial intelligence in determining who and what is seen and heard; and the financial model that creates a free market for our attention, prioritizing virality and engagement over reliable information. If these are real drivers of the infodemic, should these companies be changing how they function? Should they be adjusting their algorithms to prioritize reliable information? Should they be radically limiting micro-targeting? And, perhaps more importantly, do we want platforms making these broad decisions about speech themselves? If not, how can democratic governments step in?

In this week’s podcast, we talk with Angie Drobnic Holan, editor at Politifact, about fact-checking the infodemic, about whether fact-checking is enough and about what it’s like to work with Facebook.