Recent and serious allegations of foreign interference (FI) in Canada by the People’s Republic of China (PRC) have propelled the topic to the forefront of public discourse.

Canada is not alone in tackling this problem. Democracies around the around have had, or are having, similar discussions about the impacts of FI in their open systems after facing several major challenges.

By design, democracies invite the participation of multiple stakeholders in dialogue. Unfortunately, this openness can also be weaponized by other states to manipulate democratic systems into furthering their self-interest. Without proper tools in place to prevent such misuse of open systems or enforcement against transgressions, democracies can find themselves at a strategic disadvantage.

What Is FI?

States routinely influence one another through open diplomacy. However, FI takes place when influence crosses a certain threshold. The Canadian Security Intelligence Service Act (CSIS Act) defines this threshold as “activities within or relating to Canada that are detrimental to the interests of Canada and are clandestine or deceptive or involve a threat to any person.”

While FI can include espionage efforts, these two threat activities should not be considered synonymous. CSIS deliberately differentiates between espionage and FI in its act (in its definitions of “threats to the security of Canada” in section 2); these threat activities can involve vastly different objectives and tradecraft. For our purposes, think of espionage as an effort to collect privileged or sensitive information. FI, on the other hand, is more focused on clandestinely influencing the way in which a society or government operates.

At its core, state-backed FI is about furthering the interests of a foreign government or a political entity. FI is also not a new issue and transcends electoral cycles. While the tools, tactics and scope of how states seek to interfere in democracies have changed, the challenge of FI itself has existed for some time. Recognizing this threat early on, the US government enacted the Foreign Principal Registration Act (FARA) in 1938.

Complicating the issue of FI is the propensity of some countries, notably China, to use a combination of open, covert and “grey zone” tactics, so that someone targeted or manipulated by FI may not even realize they are part of a foreign scheme. Online efforts to influence democracies can also be difficult to investigate, track and document.

What Does FI Look Like in Democracies?

The US Department of Justice has laid several FI-related charges in recent years. In one case, two people were arrested in 2022 for allegedly “participating in a scheme to cause the forced repatriation” of a PRC national in the country. In another case earlier in 2022, several PRC-linked individuals were accused of “orchestrating a campaign” to undermine the congressional candidacy of a US military veteran.

FI is not a problem unique to the United States. In Australia, the government put new rules to the test by charging an individual in 2020 for allegedly attempting to improperly influence an Australian politician. In early 2022, the United Kingdom’s Security Service, MI5, accused a UK-based lawyer of engaging in China-linked interference activities in a targeted security warning to members of Parliament. Civil society has accused China of conducting malign disinformation operations in Taiwan, and concerns have also been expressed about China’s ability to interfere in Singapore’s affairs (Singapore now has a Foreign Interference [Countermeasures] Act).

Party leadership expends significant effort to control voices both inside (through, say, censorship) and outside China.

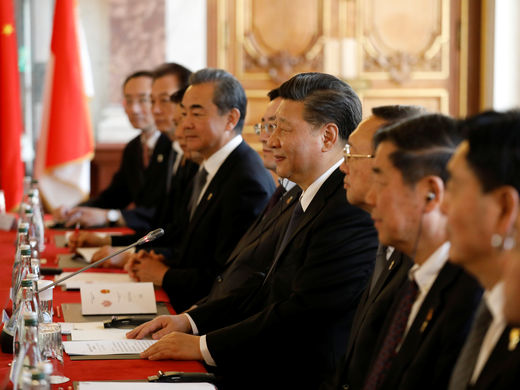

Why Does China Conduct FI?

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) uses the party-state to conduct FI to preserve the stability and legitimacy of party rule. The CCP does not want domestic or international voices to criticize China or otherwise take actions that challenge party or government policy. Ideally, the CCP would like countries around the world (including Canada) to speak favourably about China and its policies — or remain neutral. The CCP also desires for international stakeholders to not actively try to work with one another through international deals or agreements (such as the Australia-United Kingdom-United States partnership or the Indo-Pacific Quadrilateral Dialogue) to address problematic elements of CCP policy.

Party leadership expends significant effort to control voices both inside (through, say, censorship) and outside China (for example, through influence and interference efforts). At the centre of these efforts is a desire to control the voices of those the politburo perceives to be “Chinese” (such as members of the broader China-linked diaspora).

Open democracies offer groups that wish to criticize the party-state with a space to air their grievances. The CCP therefore seeks to use its United Front Work Department to “co-opt and neutralize” both openly and clandestinely those perceived to oppose the policies and authority of the state. China’s State Security and Ministry of Public Security are also key players that execute sophisticated FI operations, among other party-state actors.

What about Canada?

In Canada, FI manifests itself through the targeting of diaspora groups, academia, public servants and elected/appointed officials across multiple levels of government, among others. As a close US partner and member of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization and the Group of Seven, Canada has legitimacy on the international stage that could be used to further the interests of countries such as China. Our voice could also be used to delegitimize partner efforts to challenge authoritarianism.

Canada has limited tools to directly address foreign interference (although the Elections Act has rules about foreign financing). Unlike some partners, we don’t have a foreign agent registry; certain agents of foreign governments can operate in Canada without declaring themselves as such. The lack of a robust framework to punish FI makes the risks of conducting such activity in Canada relatively low.

CSIS notes Canada is a key target of FI from countries like China, Russia and Iran; Canada’s Communications Security Establishment has also raised alarms about these countries and “online foreign influence campaigns.” CSIS has further described China as the “foremost aggressor” of concern and indicated in 2020 that China targets Canada’s Chinese community as part of its “Fox Hunt” campaign to repatriate individuals in Canada. According to the Federal Bureau of Investigation, this campaign is also used to suppress dissent.

What Can Democracies Do?

Shining a light on the problem is a key part of the solution. We can tackle some challenges by raising awareness about FI. This awareness-building should include efforts to help those targeted by FI learn about how to detect threat activities and report them to appropriate authorities. This work requires some effort to determine who is truly the appropriate authority to deal with complaints in a reasonable manner. We must also keep in mind that many members of vulnerable diaspora communities are concerned about repercussions should they report these issues.

Critically, we should recognize FI for the nuanced problem it is and build appropriate tools to address regulatory gaps. Tools such as the United States’ FARA legislation are not perfect. However, they provide a framework through which democracies can create enforceable measures to punish those who conduct FI. Such a framework also assists officials in understanding who they are dealing with, thereby creating an additional layer of transparency that is critical for the proper functioning of a democracy.