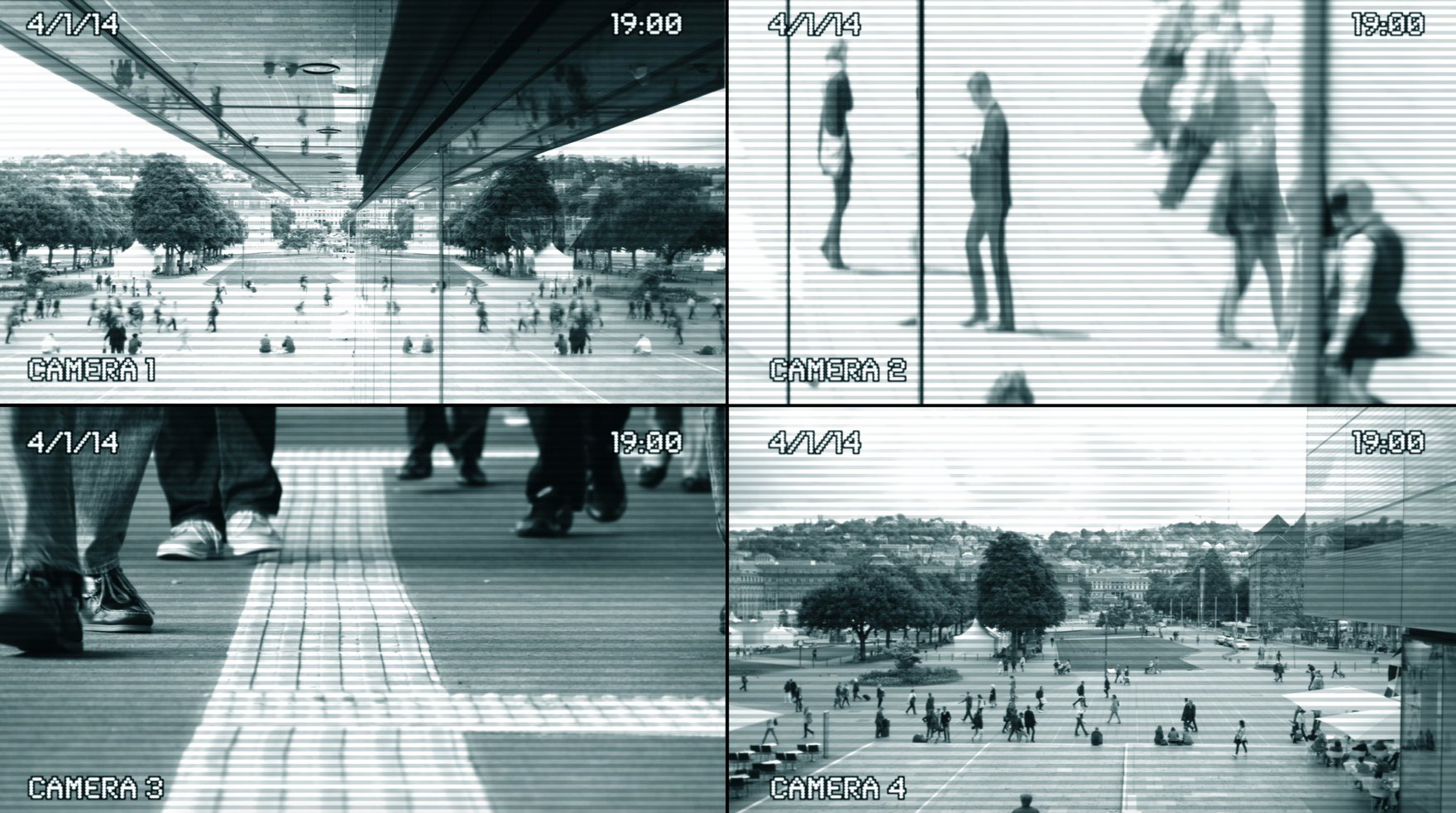

Four years ago, Edward Snowden shocked the world with a series of surveillance disclosures that forced many to rethink basic assumptions about the privacy of online activities.

In the years that have followed, we have learned much more about the role of other countries in similar cyber activities, often in partnership with Washington. The legality and oversight of these cyber-related surveillance programs fell into a murky area.

In Canada, there were legal challenges over metadata programs, court decisions that questioned whether the country’s agencies were legally offside, concern over intelligence oversight and a review process that many viewed as inadequate, plus a hurriedly drafted piece of legislation, Bill C-51 (the Anti-terrorism Act, 2015), from the then Conservative government, which sparked widespread criticism.

This week, the country’s Liberal government unveiled the first genuine attempt to overhaul Canadian surveillance and security law in decades, and it didn’t shy away from the activities Snowden exposed.

Bill C-59 (or the National Security Act, 2017) is large and complicated, requiring months of study to fully assess its implications, although there have been a trickle of notable reactions from scholars such as Craig Forcese, Kent Roach and Wesley Wark, and from civil liberties voices such as the British Columbia Civil Liberties Association and Amnesty International Canada.

At first glance, however, it addresses a legal framework that had struggled to keep pace with emerging technologies — and grapples with some of the core criticisms of the Conservatives’ earlier Bill C-51.

Leading the way is an oversight superstructure that replaces the previous, siloed approach that often left oversight commissioners with inadequate resources and legal powers. The government has promised to spend millions of dollars to give the new oversight structure the resources it needs, alongside legal powers that grant better and more effective review of Canadian activities.

The bill also places some activities of the Communications Security Establishment (CSE), the country’s signals intelligence agency, under quasi-judicial control for the first time in its history. A newly created intelligence commissioner — the position to be filled by a former judge — must authorize some activities as “reasonable” before CSE can proceed, establishing meaningful independent oversight over a set of activities that were previously at the discretion of the minister of national defence. The new quasi-judicial control could use some tweaking, however, since it is limited by its secrecy — the body only provides its reasoning to the government and the new intelligence oversight agency — and the absence of appeal mechanisms.

Better oversight alone does not effectively address the privacy-security balance, however.

The bill seeks to scale back on disruption powers, narrow the terrorism propaganda provision, and alter the much-criticized provisions that might have been applied to public protests. However, it does not address serious concerns about the information sharing within government that creates a “total information awareness” approach that barely co-exists with the country's privacy act. Moreover, the new legislation avoids entirely diving back into a debate about lawful access to digital communication, suggesting that another bill on issues such as court-oversight of Internet service provider disclosures may still be in the offing.

The aspect of the bill that may require the most careful study is the reshaping of the mandate and powers of the CSE and the expansion of the cyber security activities of the Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS).

The CSE has been at the forefront of cyber-related issues from an operational perspective, but the mandate identified in the National Defence Act required a broad interpretation to make all of its cyber security activities fit. The act states that:

The mandate of the Communications Security Establishment is

(a) to acquire and use information from the global information infrastructure for the purpose of providing foreign intelligence, in accordance with Government of Canada intelligence priorities;

(b) to provide advice, guidance and services to help ensure the protection of electronic information and of information infrastructures of importance to the Government of Canada; and

(c) to provide technical and operational assistance to federal law enforcement and security agencies in the performance of their lawful duties.

Further, the current mandate limits the geographic scope of CSE activities:

Activities carried out under paragraphs (1)(a) and (b)

(a) shall not be directed at Canadians or any person in Canada; and

(b) shall be subject to measures to protect the privacy of Canadians in the use and retention of intercepted information.

The new bill explicitly confirms that the CSE is a cyber security agency wielding defensive and, for the first time, offensive powers and granting it the ability to operate at home in Canada. This may embolden the CSE to engage in hacking of foreign governments, access information from domestic Internet companies and disrupt communication activities.

The new mandate identifies five broad activities: foreign intelligence, cyber security and information assurance, defensive cyber operations, active cyber operations, and technical and operational assistance. Given that foreign intelligence and technical/operational assistance are holdovers from the prior mandate, the new mandate reinterprets advice, guidance and service to include defensive and offensive cyber operations along with cyber security.

The inclusion of active cyber operations should capture particular attention since it signals Canada’s willingness to actively engage in hacking activities globally:

The active cyber operations aspect of the Establishment’s mandate is to carry out activities on or through the global information infrastructure to degrade, disrupt, influence, respond to or interfere with the capabilities, intentions or activities of a foreign individual, state, organization or terrorist group as they relate to international affairs, defence or security.

The bill limits these cyber operations by providing that they “must not be directed at a Canadian or at any person in Canada.” CSE’s historical defensive operations remain limited because they “must not be directed at any portion of the global information infrastructure that is in Canada,” require ministerial authorization and must be approved by the newly created intelligence commissioner. Its newly recognized offensive cyber operations face similar limitations. However, these limitations do not apply in all circumstances, including activities involving acquiring or analyzing publicly available data or cyber security, software and systems testing.

The challenge of assessing the bill will be to sort through the implications of these provisions. In recent years, there have been many disclosures about Canadian involvement in surveillance activities such as the surveillance of airport Wi-Fi or uploads and downloads to Internet storage sites. Would the new provisions explicitly permit such activities? Consider the combination of an expansive definition of infrastructure and a full mandate to acquire, use, analyze, retain or disclose infrastructure information for purposes such as research and development, testing systems or cyber security activities. The definition of infrastructure includes:

(a) any functional component, physical or logical, of the global information infrastructure; or

(b) events that occur during the interaction between two or more devices that provide services on a network — not including end-point devices that are linked to individual users — or between an individual and a machine, if the interaction is about only a functional component of the global information infrastructure.

It does not include information that could be linked to an identifiable person.

This would appear to open the door to active participation in widespread network surveillance activities and the acquisition of network traffic for the purposes of analysis, testing, retention or disclosure. These activities would not require authorization. With approval by the minister of national defence and the intelligence commissioner, the CSE can be authorized to hack into the network, install or distribute anything on the network, and do anything to remain covert. It may be even be authorized to carry out “unselected” foreign intelligence acquisition — the same mass surveillance that proved to be among the most explosive of Snowden’s revelations — so long as these activities are not directed at Canadians. There are some limitations on authorizations, which can last for up to one year. Extensions of the ministerial authorization is not subject to authorization by the new intelligence commissioner. The CSE’s or the government’s view of an identifiable person is uncertain, raising questions about whether key digital identifiers, such as Internet Protocol addresses, are identifiable in their view.

Not to be overlooked is the significant expansion of CSE’s domestic cyber security defence mandate. The agency can now acquire Canadian data and interact with designated domestic infrastructure or electronic information for the purpose of cyber defence, granting the agency a significant new role in domestic private sector cyber security.

The intelligence commissioner and the minister of national defence must authorize such activities before CSE can engage in them.

However, under Bill C-59, CSE is also granted near-limitless discretion to evaluate any system for vulnerabilities (including private sector Canadian systems or systems with extensive Canadian data) under its cyber security mandate. No authorization is required from either a minister or the intelligence commissioner to carry out such activities, although presumably CSE would still be limited by wiretapping and anti-hacking protections in the Criminal Code when accessing domestic systems without explicit authorization.

The CSIS provisions expand the collection of datasets that may also have significant cyber implications. The bill states that CSIS may only collect a dataset if it is publicly available, belongs to an approved class, or predominantly relates to non-Canadians who are outside Canada. This third category of datasets relating predominantly to non-Canadians would seemingly cover major social media and search datasets from the United States that include millions of Canadians but do not relate predominantly to Canada. This new scheme comprises a somewhat more tailored attempt to resurrect a CSIS metadata program that the Federal Court recently shut down as “unnecessary.”

Proponents will argue that these cyber-related provisions simply reflect the reality of global communications today and participation in international networks such as Five Eyes, an intelligence-sharing network including Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the United Kingdom and United States. However, Canada’s participation in these networks and the embrace of a more muscular cyber security strategy should be done with our eyes wide open, recognizing that with explicit authorization for offensive hacking of foreign governments and massive network data collection, Canada is now an active participant in the network disruption and surveillance programs whose revelation shocked many only a few years ago.