The unveiling of large language model bots such as ChatGPT — with their impressive, if flawed, output capabilities — has exploded hype around the utility of artificial intelligence (AI). At the same time, nations everywhere are waking up to how the world has become a much more dangerous place amid growing enmity between great-power rivals. Venture capitalists are taking note. They are also ahead of the curve in decoupling from China, and are increasingly abandoning long-term bets on notions such as the limitless scalability of digital platforms, in favour of pragmatic moves that might net positive cash flow on shorter timelines.

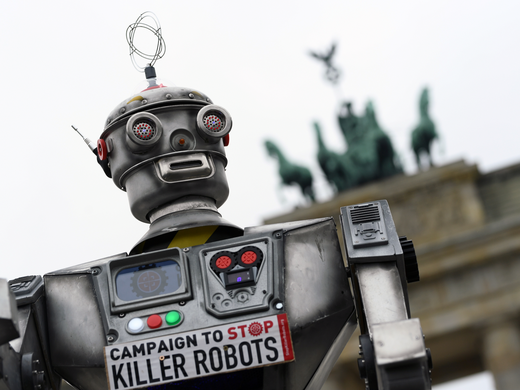

A new global arms race converging with great leaps in AI and more return-oriented investment strategies suggests at least one set of possible winners: military tech companies. Such firms are already developing intelligent battlefield tools that are, at the very least, precursors to lethal autonomous weapons systems (LAWS), otherwise known as killer robots. The valuations of these companies — most of them based in the United States, by far the world’s largest arms exporter — are poised to skyrocket as Western governments and their strategic partners re-embrace the necessity of hard power. If those valuations soar, discourse around the purported usefulness and ethical dilemmas of LAWS risks getting distorted by actors within the realm of private capital, who stand to profit from the advent of killer robots.

Among many other lessons, the conflict in Ukraine has underscored the astonishing arsenal required to wage a modern, interstate war. Members of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), whose military stockpiles have been left threadbare by their support of Ukraine for little more than a year, are now pledging huge increases in defence spending as a result. And with Russia having shattered the decades-long international consensus against land grabs by force, these massive outlays seem destined to continue for some time. Nations are bound to seek effective deterrents to safeguard their sovereignty and that of their allies.

France has increased its projected military spending by roughly one-third for 2024–2030, to US$447 billion. Law makers in Berlin last June green-lit a US$107 billion modernization of Germany’s long-neglected military. That country vows it will also soon adhere to the NATO target of member nations spending at least two percent of their GDP on defence, which NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg recently called “a floor not a ceiling.” Poland has embarked on a military spending spree that will see it double that benchmark this year. In the United States, Congress passed a US$858 billion defence bill in December — its largest ever. The bill includes authorization for the Pentagon to sign multi-year purchasing contracts to revive durable military-industrial production lines.

Countries in the Indo-Pacific unnerved by the rise of a more belligerent China are boosting their procurements as well. Japan has shed its postwar pacifist stance by announcing a defence budget 26 percent higher than that of 2022 — its biggest year-on-year increase in seven decades. Australia’s new left-leaning Labour government is preserving the enlarged allocations introduced by its Conservative predecessors. South Korea has made the growth of arms exports a key pillar of its evolving industrial policy. India, already the world’s largest arms importer, announced in February that it will spend 13 percent more on defence this year, funnelling at least US$26 billion toward acquiring extra military hardware.

This largesse is delivering a generational windfall for Western weapons manufacturers — in terms of not only current and prospective purchase orders but also an associated surge in their stock prices. From January 2022 to February 2023, various British, American and European arms producers saw their valuations increase anywhere from 35 percent, in the case of Lockheed Martin in the United States, and 60 percent, for BAE Systems in the United Kingdom, to 125 percent, for Saab in Sweden. The share price of Germany’s Rheinmetall during that time grew 190 percent. In South Korea, the country’s three main defence contractors — Korea Aerospace Industries, Hyundai Rotem and Hanwha Aerospace — saw their valuations swell by 40 to 50 percent and their foreign orders double between the beginning of 2022 and year’s end, despite a simultaneous 20 percent drop in the country’s primary stock market index.

But as much as the conflict in Ukraine, with its trenches and tank skirmishes, has been a throwback to wars fought a century ago, it has also been a proving ground for cutting-edge military technologies powered by AI. This includes products from American company Anduril, whose portfolio of hardware features autonomous aerial and marine drones. The latter, for example, are touted in company promotional material as “ideal for a variety of missions such as undersea battlespace intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance, mine counter-warfare, anti-submarine warfare, seafloor mapping and more.”

A new generation of private investors and software and robotics engineers keen on participating in the military tech sector claim they are motivated not just by profit but by a sense of civic duty.

Also present in Ukraine has been another — at times controversial — US-based tech firm, Palantir. Founded in 2003, the company began by supplying analytics software to several branches of the US government. It later drew backlash for its alleged role in facilitating human rights abuses by Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents in their tracking and arrests of undocumented immigrants. Today, Palantir’s sensor-based intelligence-gathering and real-time target acquisition software has been vital to Ukraine’s resilience. CEO Alex Karp suggested in an email to The Washington Post in late 2022 that the efficacy of Palantir’s algorithm-based warfare systems “is now so great that it equates to having tactical nuclear weapons against an adversary with only conventional ones.”

Private investors seem to fully grasp the financial opportunities of a more hostile world. Leaked audio from a tech forum held in New York in February captured a representative from America’s Frontier Fund — a venture capital platform funding US-based companies working on AI, biotechnology, aerospace and more — saying that “if the China-Taiwan situation happens, some of our investments will 10x [grow ten-fold], like overnight.”

After Palantir released its 2022 fourth-quarter earnings report in February, revealing its first-ever positive revenue, the company’s share price briefly rose 20 percent. As of mid-April, the company had a market capitalization of nearly US$18 billion. Yet some analysts claim Palantir’s current share price of around US$8.50 is a substantial bargain, given the company’s future growth potential.

A new generation of private investors and software and robotics engineers keen on participating in the military tech sector claim they are motivated not just by profit but by a sense of civic duty.

In a recent interview, Josh Wolfe, the co-founder and CEO of Lux Capital, an early backer of Anduril, noted that the US tech community has historically been somewhat averse to collaborating with the Pentagon. This spilled out into public view in early 2018, when more than 3,100 Google employees signed a letter protesting the company’s work on Project Maven, a joint endeavour with the US Department of Defense (DoD) to use machine-learning tools to enhance the targeting of drone strikes. Google later opted not to renew its contract with the DoD after it expired in 2019.

Wolfe says this began changing with the emergence of Anduril, whose founder and chief executive, Palmer Luckey, has been blunt in asking investors if they are comfortable supporting technologies that are meant to form part of a “kill chain.” In Wolfe’s telling, this has sparked a new movement within tech circles that is attracting people who are “patriotic” and “aren’t naive” about growing national security threats throughout the world. The ambitions of Project Maven, for example, are now being fulfilled by a raft of new military tech start-ups. One of these is Rebellion Defense, which is funded by Innovation Endeavors, a venture capital firm that lists its founding partner as former Google CEO Eric Schmidt.

In a profile in WIRED magazine in February, Schmidt — who was hand-picked to chair the DoD’s Defense Innovation Board in 2016, during the twilight of the Obama presidency — describes the ideal war machine as a networked system of highly mobile, lethal and inexpensive devices or drones that can gather and transmit real-time data and withstand a war of attrition. In other words: swarms of integrated killer robots linked with human operators. In an article for Foreign Affairs around the same time, Schmidt goes further: “Eventually, autonomous weaponized drones — not just unmanned aerial vehicles but also ground-based ones — will replace soldiers and manned artillery altogether.”

This vision of the future of warfare aligns with a speech given by Ukraine’s deputy prime minister and minister for digital transformation, Mykhailo Fedorov, to a NATO conference last October. Shortly beforehand, lightning counteroffensives by Ukraine had just retaken significant territory from occupying Russian forces. “In the last two weeks,” Fedorov said, “we have been convinced once again the wars of the future will be about maximum drones and minimal humans.”

If so, the country or bloc of nations that is home to tech companies that can successfully manifest killer robots currently in development — such as drones, robot dogs, anti-ship and anti-air defence systems, AI fighter pilots, self-driving tanks and more — will gain tremendous strategic advantage in the fractious, high-stakes geopolitical order now emerging. Shareholders in the firms designing and manufacturing these systems would also see exponential return on their initial investments — as has been the case with the now globalized military drone industry.

In anticipation of this, the US government on February 16 published a framework for the responsible military use of AI. The document essentially advocates that the use of AI in armed conflict be grounded in international humanitarian law and stay contained “within a responsible human chain of command and control.” However, there is a chance the risks presented by LAWS may begin to be rationalized, downplayed or outright ignored by decision makers once the profit motive and lobbying power of private capital becomes fully engaged with their development and deployment.

Among these risks is the potential for technology leakage, whereby killer robot technology, via porous sanctions or battlefield recovery, lands up in the wrong hands. For instance, high-tech drones are now being wielded by terrorists and insurgent groups against government forces in the poorest parts of Africa. Likewise, the waves of Iranian-produced kamikaze drones used by Russia to decimate civilian infrastructure in Ukraine have been found to contain American-made parts.

The software indispensable to the creation of killer robots is already being developed commercially as part of other AI systems, such as Palantir’s target acquisition software. But as ChatGPT and its competitors have shown, AI systems rushed from the lab to the open market routinely display unforeseen glitches and algorithmic errors when they encounter real-world conditions. And the margin of error with LAWS will be razor-thin. Autonomous weapons systems equipped with excellent software could greatly lessen collateral damage in war zones through a more precise use of munitions; faulty internal systems present the risk of grave accidents or targeting malfunctions that lead to civilian massacres or rapid escalation.

The splashy arrival of killer robots may even lead to an overreliance on emergent technologies to the detriment of overall military effectiveness. Russia fell into this trap over the past several years, as Vladimir Putin’s regime splurged billions of dollars on developing super weapons like hypersonic missiles, nuclear armed submarine drones and thermobaric bombs. But upon launching its invasion of Ukraine, Russia had its much-vaunted military exposed as a paper tiger, dependent on expired food rations, cheap Chinese tires, consumer cellphones and a thoroughly corrupt leadership structure.

Whether any of the proposed benefits or nightmare scenarios of killer robots materialize is an open question. Just don’t count on venture capital being patient in finding out the answer.