The world is scary and complicated, so scholars often rely on metaphors. In the twentieth century, some trade policy analysts sought to explain why so many nations became avid participants in trade liberalization, so they proposed the bicycle theory of trade. The analysts relied on the metaphor that a bicycle must move forward or the rider will fall. They argued that most nations would pedal on — negotiating bilateral, regional and, to the extent possible, multilateral agreements — because a fall risked growth and international stability.

While the theory described policy-maker behaviour in the last century, it can’t clarify why the United States, the hegemon of the global economy, and one of the biggest beneficiaries of rules-based trade, has fallen off the bike. At first glance, this position seems strange. The United States remains the world’s leading importer and exporter. Jobs are plentiful and wages are rising. In addition, the US share of global gross national product is again increasing. Yet the American people don’t feel hopeful about their future, and could vote for a former president, Donald Trump, who has a long record of protectionism and disruptive behaviour.

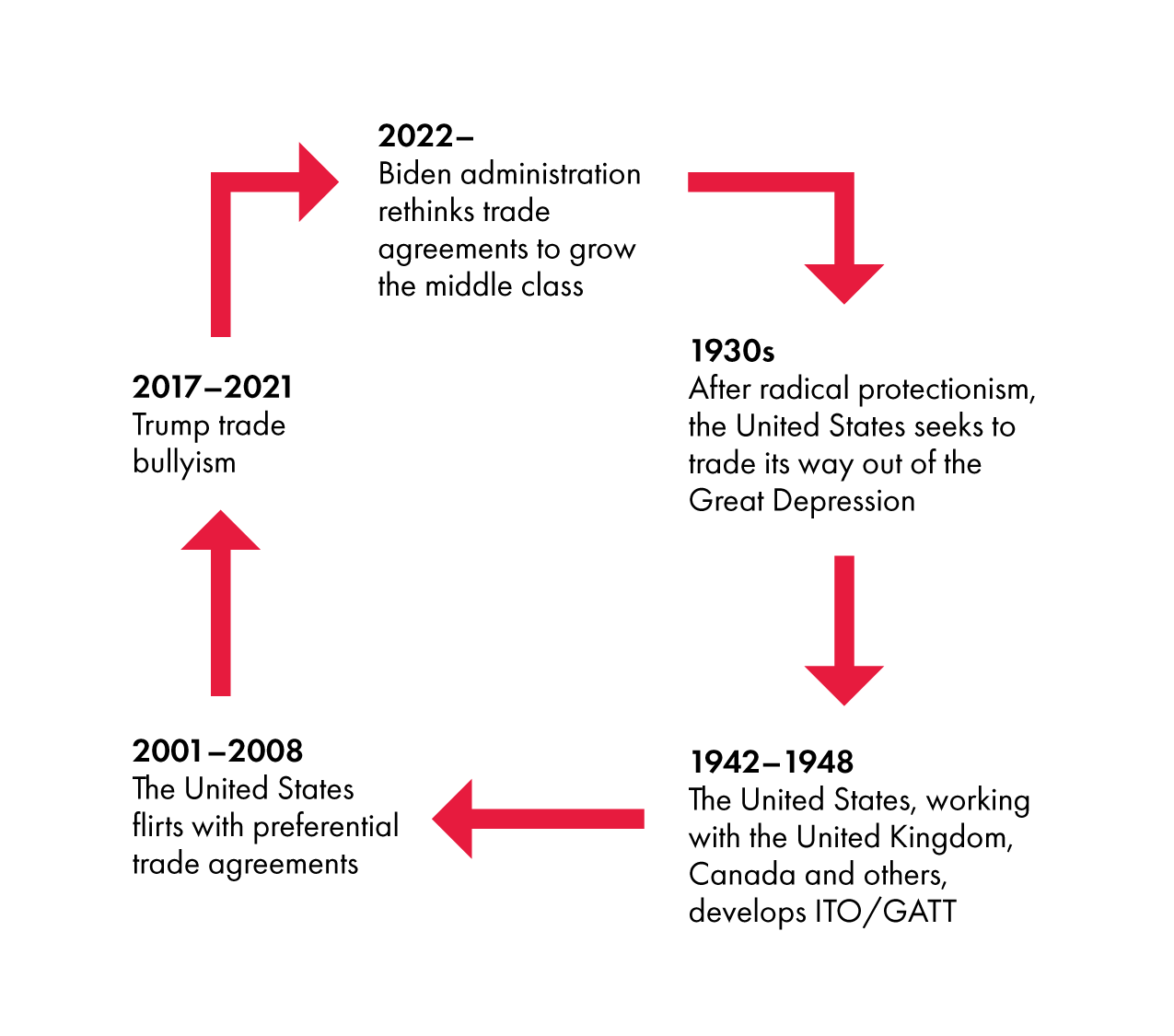

In this article, I describe how the United States evolved from being the leading demandeur of rules-based multilateral trade (1934–1999) to a nation trying to create a new approach to trade agreements that do not rely on trading market access for other concessions (see Figure 1). The Biden administration has taken on a tough task; the president cannot simply remake US trade policy at his behest — the executive and legislative branches share that authority. Congress sets out the principles and objectives for trade policy, and the executive branch is meant to act on those instructions. As evidence of the difficulties in finding common ground, I note that the US Congress has not granted new authority to negotiate trade agreements since 2015. Moreover, the United States has not signed any new trade agreements since 2019.

President Joe Biden’s administration has taken a different approach to trade than the Bush, Clinton, Obama or Trump presidencies. It has not pushed for new authority to negotiate trade agreements or adopted “buy America” provisions, and has kept some Trump tariffs in place, among other policy decisions. It is an increasingly vocal advocate of industrial policy and export controls. Hence, some view it as protectionist. But Biden trade officials argue that the recent experience of Americans, as well as US history, taught them that the current approach to trade has not sustained the middle class, nor can it protect the United States and other countries from what they deem unfair Chinese economic practices. Thus, the United States is proposing both a new approach to trade agreements and a strategy of fighting Chinese fire with Western fire (a.k.a. subsidies, export controls, “buy local” incentives and so forth).

Figure 1: America’s Twenty-First-Century Evolution on Trade

Part 1: The United States Leads Efforts to Encourage a Rules-Based System, 1934–1999

The United States relied on protectionism as a means of stimulating growth for much of its history (as Douglas A. Irwin has described in his book, Peddling Protectionism). However, policy makers turned that model on its head during the Great Depression and the Second World War. Americans suffered during the Great Depression as the economy contracted and almost 25 percent of the working-age population was unable to find work. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt understood that traditional approaches to stimulating economic growth and employment were not working; the same was true of protectionism. Building on the advice of economists, Roosevelt administration policy makers decided to experiment, and Congress approved the Reciprocal Trade Agreements Act in 1934. The law authorized Congress to task the president with negotiating bilateral trade agreements, which they hoped would increase exports and support new job creation.

During the Second World War, the president used this authority to develop the International Trade Organization (ITO). Trade was not top of mind for many of the countries of Europe, which were struggling to defeat the Nazis. So Roosevelt also relied on lend-lease, a program that provided loans to buy much-needed war matériel as leverage. After years of planning and negotiations, the United States achieved an agreement that would put in place a system of rules governing trade and competition policy. The ITO also included vague language on the goal of full employment and the need to protect workers from unfair trade competition. However, it did not include clear rules on how to reduce trade distortions arising from different countries with different regulatory approaches to these objectives.1 Moreover, the ITO was incredibly complex, and many senators were concerned about its impact on American capitalism. In addition, some senators feared the ITO could not meet the more ominous challenge of communism. The Senate never voted on the ITO. In the interim, the United States turned to the GATT, a part of the ITO that addressed trade in goods and set rules governing border measures such as tariffs. The United States gradually became a demandeur of rules-based open trade, moving from supporting bilateral trade agreements to multilateral trade liberalization under the GATT.

The United States viewed the GATT as a contract among nations regarding trade in goods. In the years that followed, the United States made major concessions on its tariffs, quotas and non-tariff barriers such as subsidies and quotas requirements, in the hopes of encouraging European recovery from the war. In this period, the United States was certainly not a free-trading nation, but one where officials recognized the benefits of reciprocity — as an example, trading concessions in tariffs for market access in computer services or lower subsidies for agriculture. From 1986 (during the Uruguay Round) through 1999, the United States led efforts to strengthen the GATT, working with the 99 other contracting parties to create the World Trade Organization (WTO). The WTO not only encouraged trade negotiations through ministerial conferences to be held every two years but also included a system of dispute settlement.

During this period, US policy makers learned that a rules-based system built on reciprocity and transparency could yield a fairer, more accountable trading system in America’s and the world’s interest. But that same system was cumbersome and incomplete because it did not address the many domestic regulatory issues that distort trade conditions among nations.

Part 2: Experimentation with Bilateral and Regional Free Trade Agreements

In 1999, the United States agreed to host its first WTO (or GATT) ministerial. The Clinton administration hoped to negotiate new rules to link labour and the environment to trade. But by 1999, some Americans concluded that the world trade system was empowering market actors to undermine labour rights, the environment and democracy. At the Seattle Ministerial, thousands took to the streets to protest the WTO; they were not receptive to efforts to include such rights in the body of the agreement. Meanwhile, in 2000, China joined the WTO. China was already adept at using trade to stimulate growth and move growing numbers of its citizens out of poverty. US policy makers at the time wanted China to join the WTO, thinking that they would have more leverage with China in the WTO than outside it. They also hoped that over time, as more Chinese moved into the middle class, China would become more democratic and accountable. But US firms began to move manufacturing to China, and many policy makers began to blame China for job losses, disinvestment and the destruction of once-thriving US communities. The United States and other countries frequently challenged Chinese practices through trade disputes at the WTO, yet found that the Chinese government did not sufficiently change course as required under WTO rules. US officials gradually concluded that multilateral leverage on China was not changing China, but rather that China was breaking the WTO. Some business leaders and policy makers became disillusioned with the WTO for not consistently holding China to account for its non-market-oriented practices.

Eventually, US policy makers suggested a strategy that might mitigate the inability of the WTO to effectively address labour and environmental issues as well as the WTO’s failure to effectively discipline China. In a 2001 op-ed written shortly after 9/11, Bush administration US Trade Representative (USTR) Robert Zoellick argued, “America’s might and light emanate from our political, military and economic vitality. Our counteroffensive must advance U.S. leadership across all these fronts.” Zoellick’s “counteroffensive” was trade, trade, trade. The United States would negotiate bilateral and regional, as well as multilateral, agreements, because these agreements would incentivize America’s trading partners to make more concessions at the WTO, which in turn would power American exports, creating ever more good jobs. These agreements also allowed the United States to incorporate more human rights, labour and environmental language into trade agreements. During the Bush and Obama presidencies, the United States approved some 12 bilateral and free trade agreements, and initiated negotiations on the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) (a WTO-plus agreement negotiated by 11 nations bordering the Pacific). But by 2016, Republican and Democratic enthusiasm for trade agreements seemed to dissipate.

Policy makers recognized that although trade liberalization could yield great benefits to consumers and exporting firms, they also come with significant costs over the short and medium term to individuals as citizens, workers and friends of the Earth.

Part 3: Trump’s Protectionist Vision

Trump believed one reason he won the 2016 election was his argument (as delivered in this speech) that trade had led to job loss as well as rural and manufacturing community devastation. He believed protectionism, reshoring incentives and bullying could reverse those effects. While the Obama administration saw the TPP as a crucial counterweight to the growing trade power of China, Trump could not care less. During his first week in office, Trump withdrew the United States from the agreement, and made it clear that trade liberalization would not be a priority. On April 29, 2017, Trump directed the Commerce Department and the Office of the USTR to review all of America’s recent trade agreements with an executive order (EO). In his EO, under “Policy,” the president states his belief that trade agreements “should enhance our economic growth, contribute favorably to our balance of trade, and strengthen the American manufacturing base.” These agreements are not fair if they harm “American workers and domestic manufacturers, farmers, and ranchers” or fail to “protect our intellectual property; and encourage domestic research and development.” Next, he made tariffs his Swiss Army knife; he used them to punish close friends such as Canada, as well as to force policy makers in China to further open their markets. With such actions, he disrupted American alliances and sent a message that when he said “America first,” he was not concerned about the implications in other countries.

Trump and his supporters argue that their approach to trade was effective. Others have asserted these tactics effectively undermined trust in America as a dependable trade partner. Trump’s tariffs and trade-related policies were discriminatory. His focus on the trade deficit as a metric for making trade policy was ineffective. Some observers assert that while Trump tactics were unfair, the United States learned it could continue to prod (even bully) other countries to achieve the policies that it wanted, including export controls subsidies and other industrial policies. In short, US policy makers learned they should turn inward. That message was also reinforced by supply chain shortages during the pandemic. Americans were shocked that despite all their trade agreements, they could not get basic supplies such as wood, infant formula or used cars.

Part 4: The Biden Approach — A Rethinking

When he took office in 2021, President Biden aimed to enable US recovery from the pandemic, rebuild trust and restore US credibility abroad. Biden chose former governor Gina Raimondo as his Secretary of Commerce and industrial policy “czar,” and Ambassador Katherine Tai as his chief trade negotiator and USTR. The USTR staff continued to negotiate the Doha Round at the WTO and monitor existing trade agreements. But inside the executive branch, policy makers were rethinking what belongs in trade agreements. Tai believed that the United States needed a different approach to trade agreements — one that did not rely on granting market access or protectionist bullying.

Tai described what went wrong in a June 2023 speech to the National Press Club: “Trusting markets to allocate capital efficiently, we designed trade rules to liberalize as much as possible, under the theory that we were facilitating the creation of a free global marketplace. We thought a rising tide would lift all boats…[but] we did not include guardrails to ensure that it would be the case.” In her view, the system incentivized lowering standards to gain greater trade, “as companies sought to minimize costs in pursuit of maximizing efficiency.” In her view, production became “increasingly consolidated in one economy — such as the PRC — which manipulates cost structures, controls key industries, and became a dominant supplier for many important goods and technologies.” Tai concluded, “Our focus has shifted from liberalization…to raising standards, building resiliency, driving sustainability, and fostering more inclusive prosperity at home and abroad.…We are using trade to create a race to the top.”

At the same time, the United States also began to devote more resources to industrial policy, modernizing infrastructure and conducting research. Congress passed the CHIPS and Science Act, which allows the United States to subsidize a wide range of emerging technologies. These industrial development efforts are directed by Raimondo, who is also tasked with increasing US exports. In 2022, the United States initiated export controls on semiconductors to certain nations, including China and Russia, to prevent these nations from using advanced chips for military purposes. Over time, these export controls got broader and tougher, making it harder for firms in Russia, China and Iran to obtain or produce such chips. US policy makers moved from directing a policy aimed at limiting China’s export growth to a policy that made it harder for these nations to produce and export advanced technologies. Moreover, these policies limit the sales of our allies, which also sold chips manufacturing components or chips. In a sense, these nations had to choose between joining the US/Western club or team China. But the approach was also a rebuke to one of the key norms of trade agreements — non-discriminatory treatment of foreign and domestic producers.

But that was not the only major change under Biden. Tai and her colleagues envisioned building a novel approach to trade based on insights from Tai’s experience in Congress. These ideas were articulated in an important paper written by Beth Baltzan (formerly Tai’s colleague at the House Committee on Ways and Means and now senior advisor to the USTR). Baltzan argued that the current trade agreement model violates the social contract because it “pits workers in one country against workers in another, as returns to capital increase while returns to labor decrease; it promotes the degradation of the environment; and it robs nations of sufficient revenues to fund the basic needs of their people.” Moreover, these policies required trading market access in one country for tariff reductions or labour rights improvements in another.

The first test case was Taiwan. In 2022, Congress passed a law encouraging negotiations toward a durable trade agreement with Taiwan. The negotiations are still in progress. However, the negotiating mandate provides insights into this new approach. It calls for negotiations for the purpose of reaching agreements with high-standard commitments and economically meaningful outcomes. For example, on labour rights, the parties aim to “(1) support the protection of internationally recognized labor rights…, (2) increase opportunities for worker voice and public engagement in implementing trade policy, (3) account for the role and responsibilities of the business community in helping to ensure the protection of workers’ rights through a focus on corporate accountability and (4) reflect more durable and inclusive trade policies that demonstrate that trade can be a force for good.” On digital trade, the parties aim to “advance outcomes in digital trade that benefit workers, consumers and businesses.” But it is unclear who decides if provisions advance such outcomes.

The Biden administration also negotiated the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework for Prosperity (IPEF) with Australia, Brunei Darussalam, Fiji, India, Indonesia, Japan, the Republic of Korea, Malaysia, New Zealand, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam. The framework had four pillars: trade; supply chains; clean energy, decarbonization and infrastructure; and tax and anti-corruption. The IPEF is designed to be flexible, meaning that IPEF partners are not required to join all four pillars. According to the White House, the IPEF will enable the United States and its allies to decide on rules of the road that ensure American workers, small businesses and ranchers can compete in the Indo-Pacific. The negotiating drafts have not been made public.

However, US trading partners and members of Congress were skeptical about this approach for several reasons. First, as noted above, the IPEF did not require nations to commit to market access in return for commitments on tariffs or non-tariff barriers. Hence, to some observers, the IPEF looked more like a non-binding standards agreement than a trade agreement. Second, Congress had not been asked for specific negotiating authority, and some members claimed they were not widely consulted on the negotiation. Third, some participating nations did not want to commit to binding enforcement for labour and environmental provisions. So, the agreement already inspired ambivalence at home and abroad. Meanwhile, officials at other key agencies such as the Department of Justice and the Federal Trade Commission were concerned that the digital trade chapter would undermine the ability of America and other countries to regulate the tech giants. When Tai went to testify on America’s trade performance in April 2024, Republicans on the House Committee on Ways and Means concluded that “the Biden Administration’s trade agenda…does little to advance the interests of American workers and producers, and has ceded the playing field to China.” They reminded Tai, “There have been no trade deals, no talks to expand free trade agreements…and no increases in market access under President Biden’s leadership.” In contrast, the chair of the Senate Finance Committee, Democrat Ron Wyden, did not criticize the new approach. But he made it clear that he wanted to see progress in market access. Wyden declared, “The United States must expand opportunities in the global market for American exporters across every industry.”

Analysis

Given this history, America’s transition from hegemonic leader of multilateral trade liberalization to hegemonic skeptic is understandable. Policy makers learned trade policy did not work for many Americans. Biden administration officials understood that neither multilateral, regional nor bilateral agreements could effectively address both the challenge of China’s approach to economic development and the need to govern workers, the environment and markets among nations with different governance expertise and priorities. Thus, the Biden administration put forward a different approach.

The Biden administration deserves kudos for trying to put humans at the heart of trade, but criticism for the lack of openness in the process. To achieve that goal, trade officials must find ways to reconcile different government priorities, will and expertise. That requires extensive consultations at home and abroad on a novel approach to trade.

In addition, to get other countries on board, the United States must offer other governments incentives for such a negotiation. Unless there is some reciprocity — some trade-off that policy makers perceive as an incentive — it is unclear to me whether other countries would want to take on such agreements.

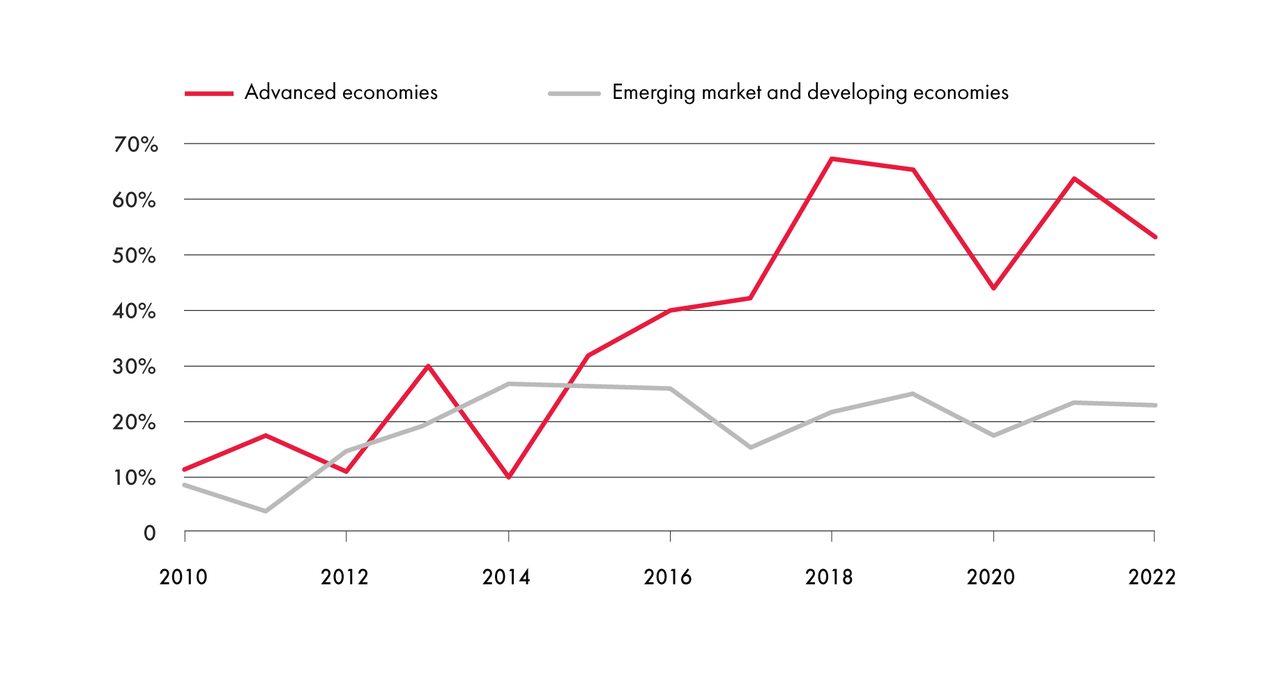

The focus on industrial policy and export controls negates the message of collaboration and mutual benefit that underpins trade agreements. Over time, these tactics could lead to less trade and global overcapacity. As Figure 2 shows, other economies are also subsidizing industry and adopting domestic policies to benefit local companies. Over time, and in sum, this focus on industrial policies could lead to trade distortions and less growth for all countries (overcapacity in AI and other emerging technologies), as I have recently described (see “The Age of AI Nationalism and Its Effects”).

Figure 2: Share of Industrial Policies within Trade Policies

If the Taiwan model is to serve as an example, its efforts to find common ground on shared rules for labour versus shared rules for digital seem contradictory. Officials have argued for centuries that how people are treated as they make goods and services is a trade issue. Individuals should be able to claim a fair share of the wealth they help to generate through trade. Yet the same should be true for data, which also generates wealth as it flows across borders, underpinning digital trade. Economist Glen Weyl, Jaron Lanier and others have argued that data is labour. After all, it is individuals who collect, organize and analyze data. Moreover, much of that data is personal data. People provide their data for free to firms that turn around and monetize this information. But like the workers of yore, humans lack bargaining power for their data, and are unable to meaningfully negotiate over payments for their data. So, why is the United States seeking standards for labour but seeking policy space for data governance? Put differently, why is the United States not trying to find a common approach to governance?

Finally, the Biden administration has taken a very internal approach to crafting this remake of trade policy. The USTR has not initiated broad consultations on how to remake trade with Congress, the American public and its allies. Policy makers in the United States and abroad will understandably fear change although they may agree change is needed. If we really want to see innovative ideas, why not ask for them through crowdsourcing or regular town halls? Sometimes outsiders can see a problem differently and more creatively than long-term insiders. For this reason, the European Union and Canada are organizing citizen assemblies where they educate their citizens about complicated policy issues and then seek (and sometimes commit to using) their ideas.

In sum, the USTR’s efforts to rethink trade agreements deserve our attention. They are trying to put America back on the bike. But if the USTR wants these agreements to be effective and enduring, the Biden administration must provide incentives to our trade partners and develop a novel approach to reciprocity. The United States should also adopt a more open and consultative approach to the process of revamping trade agreements.