Cet essai est disponible en français.

This article is a part of a Statistics Canada and CIGI collaboration to discuss data needs for a changing world.

Canadians need evidence-based and data-driven policies based on quality and timely information. The pandemic highlighted this fact, but it’s a principle that Statistics Canada has always held at the core of its values, mission, mandate and practices. The COVID-19 pandemic further demonstrated the need for data governance and sound data stewardship principles in a context of rapid digitalization and the continued shift to a digital economy. Moving forward, data stewardship frameworks and established systems and structures are absolutely vital to government departments’ abilities to fulfill their roles as public service organizations, and to continue to provide value for Canadians.

A New Data Landscape

It is absolutely critical that Statistics Canada, as a national statistical office (NSO) and public service organization, along with other government agencies and services, adapt to the new data ecosystem and digital landscape. Canada is falling behind in adjusting to rapid digitalization, exploding data volumes, the ever-increasing digital market monopolization by private companies, foreign data harvesting, and in managing the risks associated with data sharing or reuse. If Statistics Canada and the federal public service are to keep up with private companies or foreign powers in this digital data context, and to continue to provide useful insights and services for Canadians, concerns of data digitalization, data interoperability and data security must be addressed through effective data stewardship.

However, it is not sufficient to have data stewards responsible for data: as data governance expert David Plotkin argues in Data Stewardship: An Actionable Guide to Effective Data Management and Data Governance, government departments must also consult these stewards on decisions about the data that they steward, if they are to ensure that decisions are made in the best interests of those who get value from the information. Frameworks, policies and procedures are needed to ensure this, as is having a steward involved in the processes as they occur. Plotkin also writes that data stewardship involvement needs to be integrated into enterprise processes, such as in project management and systems development methodologies. Data stewardship and data governance principles must be accepted as a part of the corporate culture, and stewardship leaders need to advise, drive and support this shift.

Finally, stewardship goes beyond sound data management and standards: it is important to be mindful of the role of an NSO. Public acceptability and trust are of vital importance. Social licence, or acceptability, and public engagement are necessary for NSOs to be able to perform their duties. These are achieved through practising data stewardship and adhering to the principles of open data, as well as by ensuring transparent processes, confidentiality and security, and by communicating the value of citizens’ sharing their data.

It is the responsibility of NSOs to meet society’s need for high-quality, relevant and timely statistical information, provided with maximum transparency and while protecting privacy and confidentiality — in times of stability and crisis alike. In a rapidly changing and highly complex data context, it is essential that NSOs, and the rest of the public service, create and maintain cohesive, government-wide strategies for data ingestion, consumption and production. As Canada’s NSO, Statistics Canada must look to provide better service to the country’s now over 40 million Canadians, by facilitating partnerships and collaboration to build robust national statistical systems, drive economic growth and provide inclusive, effective services to citizens.

What Is Data Stewardship?

In an age that is now increasingly digital and characterized by exploding data volumes, any organization that is invested in the production and dissemination of quality data has its focus firmly trained on the concepts of data governance and data stewardship. Institutions, whether public or private, see the importance and overall value of sound stewardship, and are working to develop (or redevelop) their own definitions, frameworks and strategies. However, this individual activity means that concepts can vary — across sectors, across organizations, and even across internal divisions or departments. This variation is why it is important to define and contextualize how these concepts will be used.

Internally, Statistics Canada understands data stewardship as the management and oversight of data assets to ensure that they are of high quality, easily accessible, sharable, reusable and used appropriately. Data stewardship enables the proper management of data assets throughout their life cycle. Proper management includes making sure that data is generated or collected, processed, stored, managed, analyzed and communicated ethically, efficiently and effectively, in ways that address privacy preservation, confidentiality and other security requirements. It is the intergenerational curation of data assets, such that they benefit the full community of data users and are used for public good.

Data stewardship is, of course, a key function of NSOs. As such, Statistics Canada has carefully considered its understanding of data stewardship, which necessarily appears in the Statistics Canada Data Strategy (SCDS). The approach of the SCDS to data stewardship includes the four capabilities or foci of data discovery, digitalization, interoperability and management. These four concepts are fundamental principles of data stewardship and critical to enabling effective data governance, described by Plotkin as the exercise of judicious decision making and authority via policies, procedures, rules and so forth to govern data. Data stewardship is the tactical aspect of data governance, the day-to-day work that formalizes and operationalizes accountability for managing information resources ethically and effectively throughout the data life cycle. Statistics Canada is committed to renewing the SCDS to align to the renewed Data Strategy for the Federal Public Service.

The four data stewardship capabilities that Statistics Canada focuses on — data discovery, digitalization, interoperability and management — are the vehicles or mechanisms through which effective data stewardship is ensured throughout the data life cycle. Data discovery refers to the initiative to prioritize data and insights that are already present in the data ecosystem (that is, administrative data) before other collection methods are used. This prioritization reduces the survey response burden for citizens, is more cost-effective and increases the timeliness of the data. Data digitalization describes the digital transformation plan that many institutions have under way: to systematize and automate as much as possible; to collaborate with other sectors; to renew aging information technology infrastructure; and to build only when necessary to improve agility, responsiveness, timeliness and, ultimately, value. Data interoperability allows for accessing and processing data from multiple sources and then for integrating that mutually comprehensible data for linking, sharing, mapping, visualization, and other forms of representation and analysis. Finally, data management is enabled by (and enables) data governance authorities, systems and controls, and refers to the organizing, auditing, iterating and maintaining of data processes to meet ongoing information life cycle needs and to adhere to digital governance regulations, policies and procedures.

Just as an organization’s comptrollership function is ultimately responsible for the integrity of the organization’s financial processes, systems and delivery model, Statistic Canada’s data stewardship function is responsible for the integrity of data and related processes throughout the data value chain or life cycle. These operational and tactical principles of sound stewardship work together to describe a level of data maturity and sophistication that institutions around the world are striving to achieve through intentioned and prioritized data strategies. An important concept that enables this effort is standardization.

Data Stewardship and Standardization

The Standards Council of Canada defines data standards as the guidelines by which data are collected, described and recorded, as well as the accepted practices, technical requirements and terminologies for the field. Standards also provide information about the data collected to help further the understanding and interpretation of that data. In order to share, exchange, combine and understand data fully, both the format and the meaning of the data must be standardized. If standards are adhered to, data over time and from different sources can be better integrated, thereby maximizing the data’s productive value. Standards provide the basis for consolidating statistical information, increasing the capacity for interoperability by eliminating the need to conform data or metadata to new specifications, and reducing time spent cleaning and translating data — the latter a common barrier to data analysis that accounts for much of data users’ on-the-job time, according to Plotkin.

Considering traditional statistical methods, having standards in place — and the infrastructure to monitor, assess and improve those standards — also reduces the resources required to develop and maintain surveys. This is vital, as NSOs around the world are looking to harness the power of digitalization and “big data,” not only to increase the efficacy and efficiency of the data for public use, but also to reduce the survey response and financial burdens of traditional (and publicly funded) statistical systems on citizens. This is why, globally, many NSOs are incorporating data standards directly into their data strategy and data stewardship frameworks.

Through this work, Statistics Canada not only ensures that the quality of data is consistent across history and geography but also helps to equip public, private and academic sectors that produce and manage data to better integrate data from various sources, as well as to enable international partners in complying with those transnational obligations, such as the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and others, that ultimately encourage data comparability between countries.

Statistics Canada’s Aspects of Data Stewardship

Whether framed as technical, infrastructural, environmental or cultural, data stewardship understandably features prominently in the emerging data strategies throughout the public service, both domestically and internationally. Statistics Canada has built on its four-pronged definition of data stewardship (including the concepts of discovery, digitalization, interoperability and management outlined above), by developing a cohesive approach to data stewardship throughout the data value chain and including many areas of the statistical process. This approach includes a very necessary commitment to 10 aspects of data stewardship throughout the data life cycle: subject matter expertise, quality, standards, management, sharing and access, strategies, science, analytics, governance, protection and literacy (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Aspects of Data Stewardship

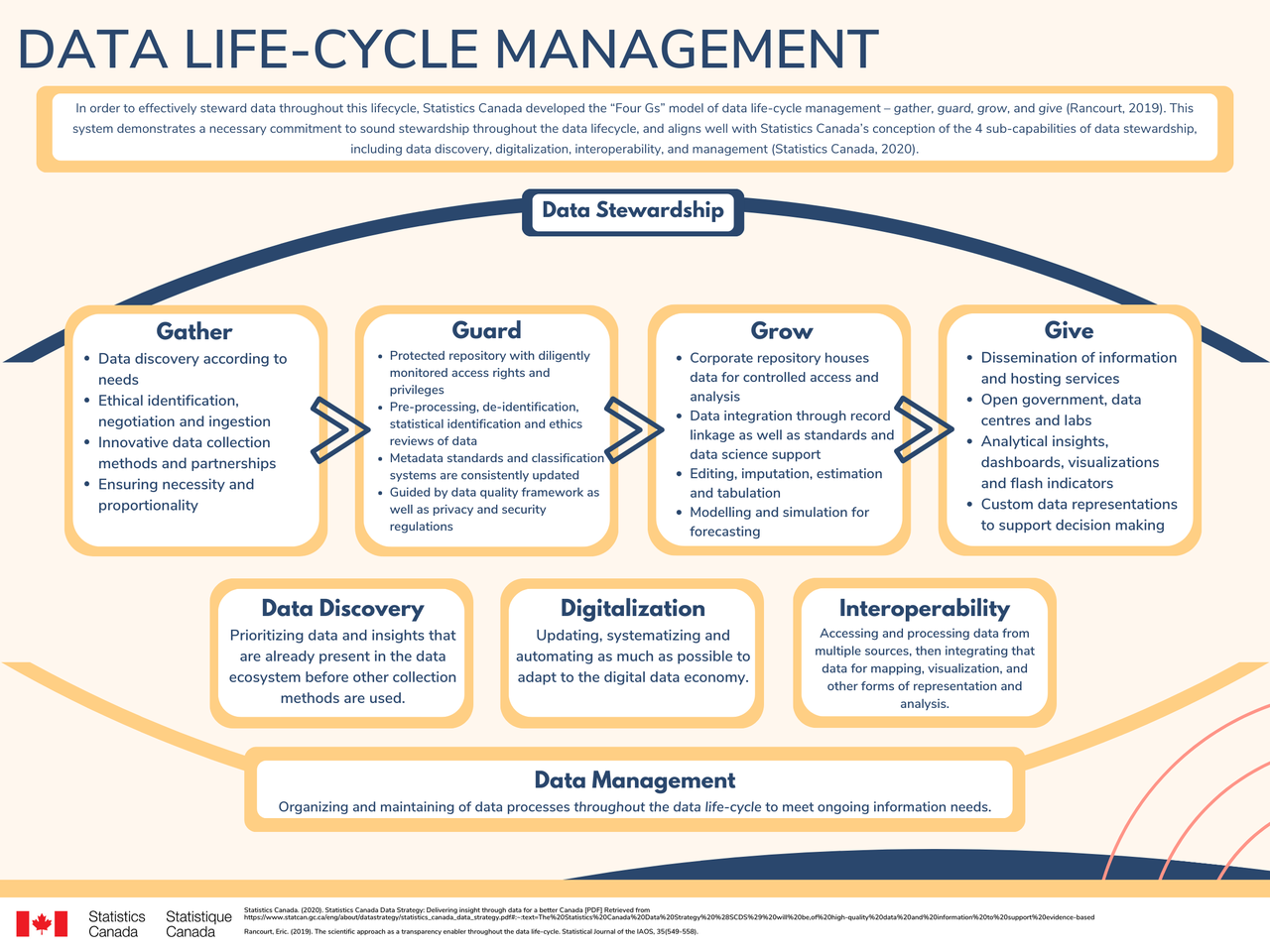

In order to effectively steward data throughout its life cycle, Eric Rancourt (Statistics Canada’s chief data officer) developed the “Four Gs” model of data life-cycle management: gather, guard, grow and give (see Figure 2).

In Rancourt’s system, gather refers to all data ingestion, including the collecting and integrating of data assets through various systems of acquisition, as well as the policy instruments and ethics-based legislative frameworks through which Statistics Canada gains access to data and information. To guard data entails paying special attention to access rights and privileges so as to adhere to the “privacy by design” principles, performing data audits and reporting on compliance, systematizing ongoing data monitoring and back-up protocols, and regularly updating metadata standards and classification systems. To grow data, the data is cleaned, organized, processed, transformed, integrated and extracted for various uses, ensuring its optimization and adhering to (and continually developing) data quality frameworks. Finally, the give function means ensuring data access and interoperability, that data dissemination occurs regularly and with quality and accessibility, and that the appropriate metadata is made available based on enterprise requirements.

Figure 2: The “Four Gs” of Data Stewardship Aligned to the SCDS’s Four Capabilities of Data Stewardship

The goal for Statistics Canada, and the public service more broadly, is to increase data discoverability and be “open by design,” having sharable and open data, metadata, metainformation and analysis. Organizing data stewardship activities along these data life-cycle phases and aligning them to our overall role as an NSO — which indeed, is to gather, guard, grow and give data — has been extremely valuable. It has allowed us to ensure that data is efficiently and optimally used and reused, that high-quality data is consistently discoverable and accessible, that expertise is appropriately leveraged, that standardization is maintained, and that public trust and engagement are preserved and encouraged, by operating ethically and transparently. Ultimately, it ensures our adherence to the FAIR Guiding Principles for scientific data management and stewardship — FAIR standing for findable, accessible, interoperable and reusable — principles developed by a diverse set of stakeholders in 2016 to guide those “wishing to enhance the reusability of their data holdings” and “put specific emphasis on enhancing the ability of machines to automatically find and use the data, in addition to supporting its reuse by individuals.”

NSOs as Subject Matter Experts in Data and Statistical Systems

According to its mandate under the Statistics Act (1985), Statistics Canada is required to collect, compile, analyze, abstract and publish statistical information relating to the commercial, industrial, financial, socio-cultural, economic, and other activities and conditions of the people of Canada. Consistent with the United Nations’ Fundamental Principles of Official Statistics, the agency’s mission is to provide Canadians with high-quality statistical information that matters, delivering insights for a better country for everyone, while maintaining trust, practical purpose, caring and inclusivity, and by remaining curious and innovative.

In order to fulfill our mandate in the current context of exploding data volumes and digitalization, and in order to remain consistent with the principles outlined by the United Nations for official statistics, Statistics Canada and other NSOs around the world have to continue to innovate and remain agile. Missing, misusing, ineffectively reusing or inefficiently sharing data has a direct impact on the ability of the data to provide adequate information about life in Canada, which in turn hinders the ability of decision makers to develop, evaluate and improve public policies. Agencies must therefore adapt their data stewardship roles and investigate new sources of data and new methods of collecting, cleaning and analysis to continue to provide statistical information that retains practical utility. Statistics Canada must remain committed to improving standardization and governance around accessing and sharing these data sources. As subject matter experts and public servants, statisticians and data professionals have an ethical responsibility to provide transparent support and guidance in these areas.

Sound data stewardship has societal benefit and contributes to the public good because it enables ethical operation, which begets the trust, social licence and public support necessary for NSOs’ work. It minimizes data misuse and enables reuse, allowing us to access data already in the ecosystem. It also facilitates data sharing and the use of new, complimentary data sources. All of these functions either directly or indirectly improve public trust and increase engagement, by saving time and money, decreasing response burden, increasing data value and better enabling the communication of that value to Canadians. Sound data stewardship is consistent with the call from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) for a shift from a “vicious cycle” of statistical underdevelopment to a “virtuous data cycle.” In its Development Co-operation Report 2017, the OECD discussed the role of national statistical systems in the data revolution, stating that increasing efforts in planning and production, strong data dissemination, and the communication of data’s value to citizens and partners results in a more productive and virtuous approach.

It’s been established by the UN Economic and Social Council that NSOs are well positioned to perform the data stewardship function. It is a relatively common practice for NSOs to facilitate statistician secondments to other government departments and agencies and to support decision making related to data and the statistical process. NSOs are naturally well positioned to assume a data stewardship role, not only because of their subject matter expertise in engaging strategically with data, but because of their expertise in data governance and stewardship, their non-partisan nature, and their sound data foundations of standards, high-quality frameworks and focus on privacy protection. NSOs, as experts in statistical systems as well as in data governance and stewardship, have the unique experience and ability to situate data collected at the macro-level, contextualizing the relationships between different domains, which better enables sound stewardship, brings greater value to the data and enhances analysis.

In a context where NSOs are actively supporting data-related projects occurring throughout government, and where Canada’s NSO is internationally renowned, what might Statistics Canada’s contribution look like, in what is known to be an important shift to a whole-of-government approach to data stewardship? This shift was embodied in the collaborative partnership between Statistics Canada, the Privy Council’s Office and the Treasury Board Secretariat to set “renewed priorities, goals and expectations,” as released in the 2023–2026 Data Strategy for the Federal Public Service. This partnership leveraged each organization’s subject matter expertise and legislative coverage to create a renewed data strategy in a way that would best position the public service to provide evidence-based advice to ministers and better support the strategic use of data, while maintaining a steadfast commitment to protecting citizens’ privacy.

The Changing Role of NSOs in Data Stewardship: What’s at Stake?

The issue remains that many organizations involved with research do not currently have sufficient policies governing the management of data, according to a gap analysis released in 2008 by Research Data Canada. Where policies exist, the principles or framework on which they are based are unclear or implicit. There are huge custodial gaps throughout the data life cycle, and no mechanisms to determine, assess or enforce roles and responsibilities. This same gap analysis reported that very few agencies possess the necessary skills, policies and expertise for collecting, preserving and managing data or for making it publicly accessible on the scale required. Industry professionals are still identifying inefficiencies and issues, and it is understood — unequivocally — that data stewardship is the key. The task, now, is to make data stewardship activities widespread and supported by specially trained data scientists and information professionals. The goal is to have researchers that are well educated on the principles and importance of data stewardship, and cognizant of their own roles and responsibilities in this regard. With the rapidly accelerating proliferation of data and the increasing demand for, and potential of, data sharing and collaboration, NSOs and public governance organizations alike need to reimagine data stewardship as a function and role encompassing a wider range of purposes and responsibilities.

The truth is, as Robert Fay and Michel Girard have described in an earlier essay in this series, despite being a world leader in official statistics, Canada is falling behind in the digital data economy; in an increasingly digital global economy, where data is a powerful asset, it is in the country’s best interests to address this gap as soon as possible. Fay and Girard point out that current practices, legislation and tools are not conducive to smart and secure data sharing, and by extension, effective data governance. Recommendations have been made, widely and for years, for the federal public service to build a national framework for data stewardship, sharing and reuse. Fay and Girard argue that such a data stewardship framework is critical to properly treating data like a strategic asset, and should facilitate data collaboratives while also asserting sovereignty of national data. One of the most important actions the Canadian government can take to empower and facilitate data sharing is to build such a data-sharing infrastructure.

Initiatives are already under way, at Statistics Canada and across the public service, to correct this, and to coordinate a whole-of-government approach to the stewardship of data collected from public, private and industrial sources. Canada’s Digital Charter was developed to ensure that privacy is protected and trust maintained, that data-driven innovation is human-centred, and that Canadian organizations can be world-leading in innovations that fully embrace the benefits of the digital economy. The Digital Charter Implementation Act (2022) modernized this framework for the protection of personal information in the private sector and introduced new rules for the development and deployment of artificial intelligence (AI) through three proposed acts: the Consumer Privacy Protection Act, the Artificial Intelligence and Data Act, and the Personal Information and Data Protection Tribunal Act.

Other initiatives — including developing sector-specific national data strategies and agency-specific stewardship frameworks; creating offices and departments at the federal level to focus on data stewardship; appointing a chief data officer of Canada; developing our machine-learning and AI capabilities; prioritizing standardization and data sharing; and emphasizing data foundations and skills — are all going to be vital pieces of the overall data strategy puzzle, and are necessary to improve our national statistical system and to continue providing value for Canadians. This zealous growth and development, in terms of treating data as an asset, are also mirrored by our NSO collaborators internationally.

While there are no statistical methods or stewardship frameworks that are an optimal fit for all circumstances, determining user needs, progressional goals and the benefit to citizens that is being pursued will enable the development of fit-for-purpose methods and approaches. NSOs have had to continue to shift their perspectives of what “good data” means, and in doing so, have more fully opened themselves up to the possibilities that come with strategic partnerships and engaging further with big data. The statistician’s tools of surveys and administrative data are being combined with innovative methods, such as flash estimates, adjustments to variable attributes, self-reported experiences and the leveraging of administrative sources, to provide the detailed and broad-scope data necessary to inform the public and enable the making of policy decisions with efficacy and efficiency.

This innovation is certainly exciting and promising, but the rapid changes in the digital economy that have been spurring this growth and development have also exposed serious issues. Data gaps have been identified, the importance of timeliness has been emphasized, and questions about privacy, confidentiality and public trust have been raised, all highlighting the need for effective and coordinated data stewardship initiatives — at home, and around the world.

Conclusion

Whether to enable data-driven decision making, or to address other national data concerns such as foreign data harvesting and the growing power of private companies in the digital market, coordination and innovation are necessary to provide better outcomes for Canadians. To achieve these results, the Canadian public service requires a cohesive, whole-of-government approach to data governance and stewardship, with consistent federal buy-in and directed implementation. Although the need is clear enough, questions remain about how best to move forward. How does the public service create the infrastructure and policies necessary to accomplish this? What is the role of the NSO in this initiative? How best can we improve data sharing and data use (and reuse), while remaining ethical and maintaining public trust and social acceptability? These are the questions that require our immediate attention if the federal public service is going to maintain relevance and public trust, and if Canada is going to keep pace in this rapidly evolving digital data context.

© His Majesty the King in Right of Canada, as represented by the Minister for Statistics Canada, 2024. For use and/or reproduction of this work, please review the terms of the Statistics Canada Open Licence.