China has lots of data. By one estimate, the country produced 7.6 zettabytes of data in 2018 and will account for 27.8 percent of the global total by 2025, surpassing the United States (Reinsel et al. 2019). The world’s largest population of internet users generates vast troves of data as citizens go online to access information, buy and sell products, make payments, chat, order taxis, learn, and consume and produce entertainment. Meanwhile, the world’s largest network of surveillance cameras watches their every movement and public services are digitalizing.

Unlocking the value of all this data is a major theme in the Chinese government’s digital strategy — one linked to important security, public policy and economic objectives. China’s government considers data not only as a tool to cement its authoritarian rule (Hoffman 2019; Mozur, Xiao and Liu 2022), but also as an economic “factor of production” on par with land, labour, capital and technology — a foundation for national power and competitiveness (CCP Central Committee 2019; CCP Central Committee and State Council 2020). It wants to harness data’s potential to drive digital transformation, innovation and the upgrading of China’s “real economy” (Creemers, Costigan and Webster 2022). By the end of 2025, Beijing wants an efficient market where companies and government bureaucracies share and trade more data (State Council 2021).

Numbers are not everything, however. China faces challenges in getting good data where needed. For example, tech firms are struggling to find enough artificial intelligence (AI) training data, an increasingly pressing issue amid fierce competition with the United States to develop the most powerful large language models (CAICT 2023a). Additionally, as of 2016, more than 80 percent of China’s information and data resources were said to be jealously kept by government bureaucracies (Beijing Daily 2016), hindering economic development and efficient governance. To tear down these “data islands” and match supply with demand, policy makers are stepping in.

Concerns around national security and socio-economic stability in recent years have led to a massive regulatory overhaul of China’s digital economy. A data governance regime is now in place, and regulators have cracked down on big tech’s data monopolies and abuses of citizens’ personal information (Reuters 2021; He 2023; Zhang 2024). The focus has therefore shifted to a key missing piece of the puzzle: creating a data trading market for the “orderly sharing of data” (He 2020), which will boost productivity and public welfare while safeguarding security and protecting personal data — under the close watch of the party-state (Arcesati and Groenewegen-Lau 2023).

This essay illuminates this ongoing project by zooming in on the development of local data exchanges — essentially, marketplaces for data. The authors first trace the policy, regulatory and institutional context, explaining how and why China’s newly established data exchanges differ from similar experiments of the past. The authors then present key findings from a review of 17 Chinese data exchanges, including their business models, ownership structures, regulatory arrangements, product lists and track record of brokering deals, based on information available on their websites and other public records.

The authors find that these exchanges, especially the more institutionalized ones in Beijing, Shanghai, Shenzhen, Guiyang and Guangzhou, are piloting solutions to some challenges in data economics and governance that are common to other jurisdictions, such as data ownership, data valuation and trust building between data providers and buyers. They are also emerging as innovative testing grounds in new areas: trading of AI training sets, cross-border data transfer and the marketization of public data. At the same time, the authors’ observation suggests that the state-centric feature of China’s data market may constrain its further development.

Data Trading in China: Progress, Setbacks, Institutionalization

For all the hype around China’s data advantage (Lee 2018), Chinese policy makers and leading experts worry that this potential has yet to be realized. To multiply other factors of production, they believe data must flow to those economic actors that can generate value from it. In other words, China needs to “activate the factor value of data” through an efficient data trading market (Yu 2021) and “data resource system” — a foundation toward digital development on equal footing as infrastructure (CCP Central Committee and State Council 2023).

Data exchanges are not new. Following the release of the national strategy for big data development in 2015 (State Council 2015), dozens of pilot data trading platforms mushroomed across the country (Shen and Zhang 2022). They function as intermediary institutions where organizations can buy and sell data products, query some data sets or access related services, such as cleaning, visualization and desensitization. Products run the gamut from training data for autonomous vehicles to corporate credit information. Until recently, however, those pilots were empty shells, accounting for an underwhelming two percent of China’s total data trading activity in 2021 (China Mobile 2023), most of which is carried out over the counter.

The problem was straightforward: Without laws, regulations and standards in the areas of data security, personal information protection and data trading, nobody trusted the system — especially not tech firms, who typically like to freely profit off personal data but not undersell the products they develop through processing it. How to properly value and price data assets, define rights of ownership and use, and find trustworthy providers, sellers as well as third-party providers for key services (such as security audits and dispute arbitration), were big questions. Meanwhile, China’s data black market has thrived, reaching a scale of CNY 150 billion in 2021 (Shen and Zhang 2022).

This chaotic situation did not sit well with the government’s resolve to crack down on monopolies, leaks, theft and misuse of citizens’ data by private actors (Shen 2021). In 2021, a new wave of data exchanges began to emerge that, unlike their predecessors, are supposed to operate under tighter government control and within clearer legal boundaries (CAICT 2023b). Authorities hope this “data trading system 2.0” will fix the regional and bureaucratic turf wars of the past (Duan 2022). Besides foundational legislation to protect data security and personal information,1 a dedicated National Data Administration was created to oversee China’s data resources and transactions (Reuters 2023).

Issues around data ownership and pricing, as well as a persistent lack of trust, continue to disincentivize companies from trading their data in the market, leading to a supply bottleneck.

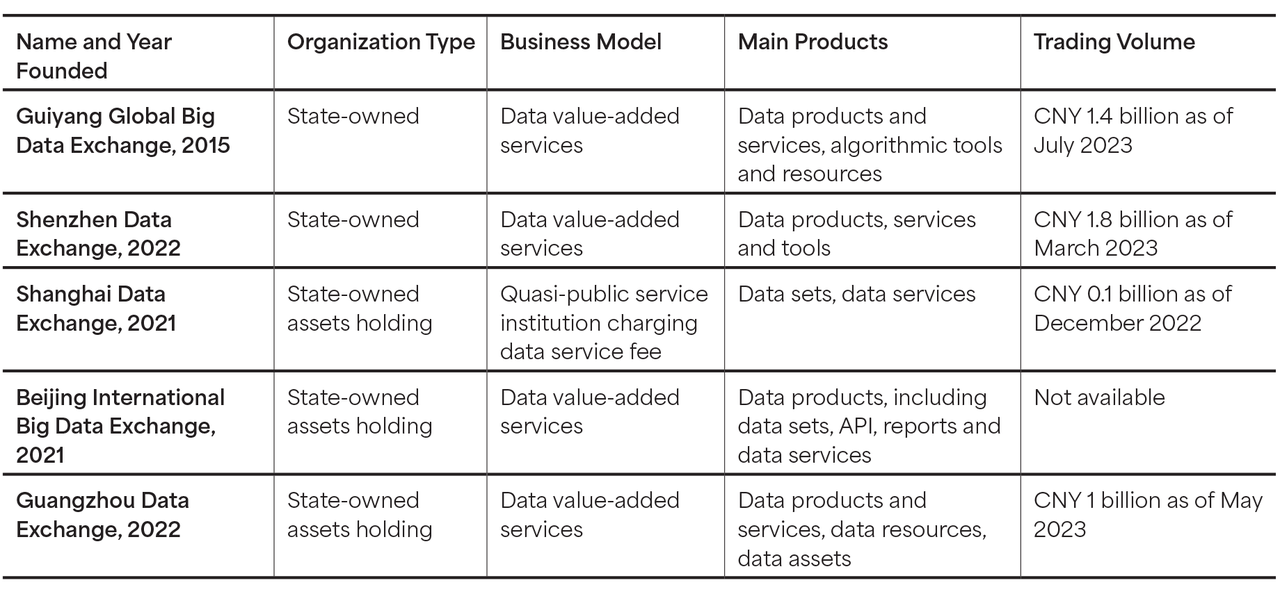

Since 2021, there has been progress and setbacks. On the one hand, data exchanges are seeing more activity: The data exchanges of Shenzhen, Guiyang and Guangzhou reached a trading volume of more than CNY 1 billion each as of mid-2023 (see Table 1). By comparison, the Guiyang Big Data Exchange, dubbed “the big data valley of China,” had an annual trading volume of less than CNY 5 million before its restructuring (Mu 2021). On the other hand, this volume is still limited compared to the huge size of China’s big data industry and total data trading. Issues around data ownership and pricing, as well as a persistent lack of trust, continue to disincentivize companies from trading their data in the market, leading to a supply bottleneck.

To solve this, central and local authorities are striving to bring greater legal and regulatory clarity around data transactions.2 The Data Security Law called for a “data exchange market” where intermediaries verify traders and have them explain the origin of the data they are selling, to avoid compromising any personal information or other sensitive data.3

One key policy, the Opinions on Building a Basic Data System to More Effectively Maximize the Role of Data Elements (also known as the Twenty Data Measures) from December 2022 (CCP Central Committee and State Council 2022), encouraged experimentation around issues such as pricing models and data property rights. Following this impetus, the data exchanges of Shenzhen, Guiyang, Shanghai, Beijing and, to a lesser extent, Guangzhou, began trialling and testing new solutions.

Table 1: The Five Major Data Exchanges in China

Local Data Exchanges as Supervisory Bodies, Matchmakers and Testing Grounds

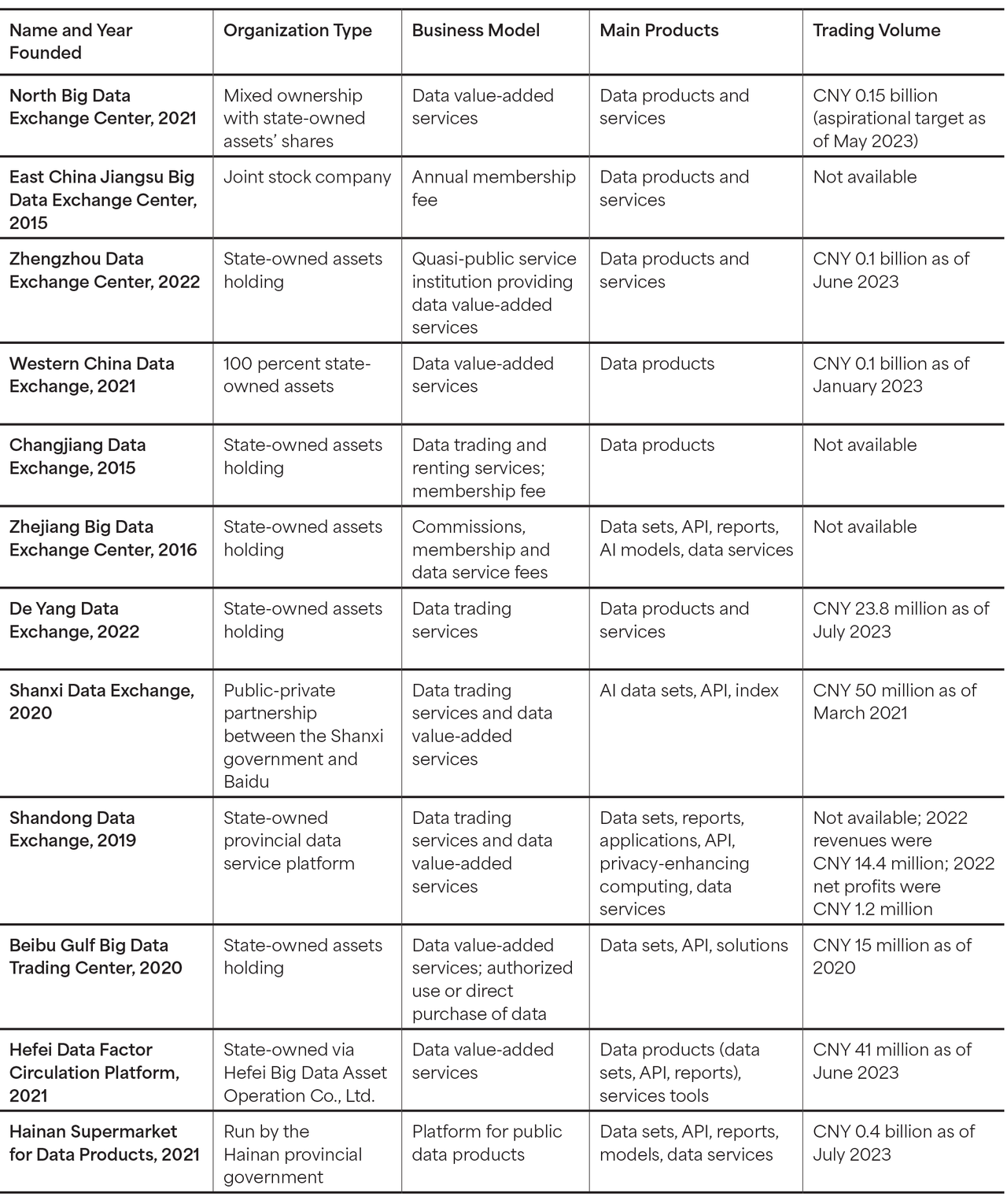

The creation of regulated exchanges with strict oversight over the whole trading process should put every link of the chain under proper supervision. Most of China’s newer data exchanges are tightly controlled by the state through various ownership arrangements (see Tables 1 and 2). The Guiyang Global Big Data Exchange underwent restructuring from private to 100 percent state control. Government backing, coupled with the rapid commercialization of new technologies and a more mature regulatory environment, have turned these exchanges from simple intermediaries into full-fledged service providers with a supervisor’s hat.

Not only do the exchanges introduce and certify new buyers and sellers, but they also take charge of compliance verifications, security and personal information protection assessments and technical support. Moreover, several exchanges have developed their own rules and guidelines, covering issues ranging from catalogues of data prohibited from trading to specific transaction standards.4 In Guangdong, the local government tasked “chief data officers” to coordinate the use of public data across government departments (Xiao and Zeng 2022).

Table 2: Other Active Data Exchanges

The first challenge is to determine ownership, which is tricky because data is a semi-public good and the allocation of related property rights among consumers and firms is ambiguous (El-Dardiry, Dinkova and Overvest 2021). Due to such ambiguity, until recently, data transactions in China were left in a legal limbo. The Twenty Data Measures marked an important step forward by dividing the legal rights of participants in the data market into three categories: ownership of data resources, rights to process and use, and rights to commercialize data. This policy is slowly paving the way for clearer data ownership rules and systems upon which data can be legally traded in China.

Some data exchanges introduced data ownership registration systems to certify the different rights associated with the data being traded on their platform, as well as market entity registration for providers and buyers (Zhejiang Lab et al. 2022). The certificates can be used as a legal basis for data trading, as well as for other purposes, such as financing and debt repayment, incorporating data assets into balance sheets, accounting and dispute resolution (Shenzhen Development and Reform Commission 2023). This approach could incentivize more companies to buy or sell data via institutional exchanges; for example, by guaranteeing the protection of the property rights and interests of data processors such as digital platform companies (Zhang and Xia 2023a).

Digital technologies, such as blockchain, privacy-enhancing technology (PET) and federated learning, are helping with traceability by certifying different data rights throughout the whole data trading process. Data owners and processers can be granted different levels of control, and the latter can only access the information required for processing and using the data, ensuring that “data being traded can be used but not seen” (Du 2022; Zhang 2023). Digital technologies also allow for the tracing of the source, transfer history and final use of the traded data.

A second challenge is to put a price tag on data, which, until recently, was left up for negotiation between providers and buyers. Combined with the scenario-based, highly customized features of data transactions, this approach easily leads to chaos and extortion. Large digital platforms, for example, can charge higher prices thanks to their sheer data power (Zhang and Xia 2023b).

Both government officials and professional associations have offered recommendations for data valuation and pricing. Wang Jiandong, deputy director of the National Development and Reform Commission’s (NDRC’s) Price Monitoring Center in 2023, advocated using cost pricing for data resources and an income-based approach for data assets. The former considers all types of investment, such as labour, time and equipment in data collection and standardization, plus data quality and privacy, to estimate the value of data resources. The latter, which Wang recommended for data assets, sets a price based on the expected income from future value (Yu 2023). By contrast, the China Appraisal Society (2020) did not differentiate between data resources and data assets and suggested considering a combination of costs, expected income and historic prices.

Some exchanges introduced recommendations and guidelines in this regard. Once a data provider has made an initial offer, the data exchanges or third-party agencies set a reference price, considering both the embedded costs in the data as well as the benefits that buyers could derive from it, plus other factors such as consumers’ expectations, supply and demand, historic prices and customer segments. Importantly, the central government seems to favour the exploration of data-pricing formation mechanisms through close cooperation with the data exchanges. The Price Monitoring Center began working with exchanges in 2023 to valuate data assets and test pricing mechanisms.

A third challenge is to establish trust in the market, absent which providers and buyers will continue to prefer over-the-counter trading over institutional channels — with all the privacy, security and legal risks that come with it. To overcome this, several exchanges are trying to create trusted ecosystems. Providers in data-rich sectors, such as utilities and internet platforms, as well as buyers, such as commercial banks, government agencies and AI companies, are incorporated into the ecosystem alongside third-party service providers. The exchanges handle basic services and supervise trading, while third parties deal with value-added services, such as data-quality certification, security and compliance verifications, and dispute resolution.

Data exchanges can also build trust by introducing high-quality products, acting as matchmakers for transactions that otherwise may not materialize.

For example, the Shenzhen Data Exchange brokered a loan agreement between China Everbright Bank’s Shenzhen branch and an AI infrastructure company, Shenzhen Weiyan Technology, based on the latter’s data products listed on the exchange (Tang 2023; Zhu 2023). The ecosystem around the exchange, which includes law firms and other third-party service providers that assist with determining data rights and valuation, assessing data quality, and verifying compliance, played a key role in facilitating the deal.

Data exchanges can also build trust by introducing high-quality products, acting as matchmakers for transactions that otherwise may not materialize. For example, one enterprise’s electricity usage data product on sale on the Shenzhen Data Exchange was used by a local government bureau to evaluate whether to grant companies the high and new technology enterprise status, one of China’s main tax incentives for innovation. Based on the same information, the Bank of Ningbo approved a loan to an electronic device manufacturer (Pan 2023).

Trust building is also a precondition to personal data trading, whose scope is extremely restricted under the Personal Information Protection Law of 2021.5 The Guiyang Global Big Data Exchange became the first to carry out personal data trading. Based on PET and other digital technologies, the recruiting platform Haohuo desensitized the resumés of job seekers as data products, such that any personally identifiable information would be hidden from users. The resumé data product was then listed on the exchange, which assigned it a reference price, while a law firm provided a legal assessment. Individuals whose resumés were traded would, at least on paper, receive a share of the revenues from Haohuo (Fang 2023).

It is important to note that, so far, the successful cases of deals brokered by China’s main data exchanges are largely due to government coordination among state-owned or state-linked participants. This makes it challenging to determine the extent to which participation in the ecosystem is even voluntary. For example, the data asset-based credit line to Shenzhen Weiyan Technology was instructed by the Shenzhen Municipal Government and the city’s financial supervision agencies. Many deals brokered in Guiyang, Beijing and Shanghai seem to have followed the same model.

Emerging Trends: Trading Data for AI Training, for Public Services and Across Borders

Chinese data exchanges are also tackling emerging challenges that are relevant for other data valuation and trading efforts around the world. These include the rapid growth of AI training data trading, cross-border data trading and the trading of public (government) data.

Amid booming demand and strict legal and regulatory requirements, China’s labour-intensive AI training data collection and annotation market is changing (Matsakis 2023). Initially reliant on their own teams and crowdsourcing, AI firms have set up dedicated bases for data collection and annotation (labelling) — key steps in preparing data for model training. Baidu, one of China’s leading tech giants, jointly built one such base with the Shanxi Data Exchange platform. The base employs 2,000 data annotators,6 with popular use cases spanning autonomous driving and biometric recognition.

The Shanxi Data Exchange platform aims to become China’s biggest marketplace for AI data products in China and a one-stop “data factory” for collection and annotation. As of this writing, 381 data products were listed on the exchange, 261 being AI-related.7 Looking ahead, it is possible that more AI training data will be collected, annotated and offered to tech companies through data exchanges. Other data exchanges, such as the Beijing International Big Data Exchange, are already catching up and listing their own AI training data products to ride the wave of AI development.

By contrast, only a few exchanges have started offering cross-border data-trading services. Among them, only the Shenzhen Data Exchange has conducted trials, whereas the Shanghai Data Exchange appears to only provide data import services on its international data board (Shanghai Observer 2023).8 The Beijing International Big Data Exchange, meanwhile, offers data hosting and desensitization services to multinational corporations operating in China (Chaoyang District People’s Government of Beijing Municipality 2022). That Shenzhen is an isolated case is not surprising, given China’s extremely stringent localization requirements and security review process for data exports.

As of March 2023, 16 cross-border deals had been closed through the Shenzhen Data Exchange (Shenzhen Municipal People’s Government 2023), for a total value of more than CNY 11 million (Gong 2022). The first deal, worth CNY 5 million, involved a foreign hedge fund purchasing ChinaScope’s flagship data product, the SmarTag news analysis engine, which uses a natural language processing algorithm to convert unstructured Chinese language news text into machine-readable metadata. The product compiles sentiment indicators linked to Chinese companies, supporting market analysis (Yuan 2022).

Here, again, the impetus came from the central government. The Ministry of Commerce has been trying to encourage free trade zones in China to pilot “safe and orderly” cross-border trading since 2020 (Sino-German Cooperation on Industrie 4.0 2020), with few results. This move probably prompted the government to bet on Shenzhen (NDRC and State Council 2022). The city was also the first locality in China to define data ownership rights and is trialling AI data trading with Hong Kong (Yuan 2022).

Despite a nearly decade-long effort, China’s open-data government platforms are still marred by quality problems, with as much as 85 percent of data collected and made available for public inquiry said to be incomplete.

The sustainability of these trials is far from clear. The powerful and security-focused Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC) has been dragging its feet over most applications for data export security review, which is required when sensitive data such as personal information and “important” or “core national” data is involved (Arcesati and Groenewegen-Lau 2023). The CAC recently announced a major policy relaxation that would let business, not regulators, decide when cross-border data flows are necessary for their global operations (CAC 2024). However, implementation will need to follow.

The government would like data exchanges to work with the CAC on these security assessments, but it has not given them the policy space and regulatory certainty to do so. The party-state’s ongoing push to obscure from foreign eyes more and more data about China’s economy, science and technology, and industries (Brussee and von Carnap 2024) casts doubt on the future of cross-border data trading.

Another space to watch is the trading of public data, a prerequisite for economic and public policy innovation around the world. Despite a nearly decade-long effort, China’s open-data government platforms are still marred by quality problems, with as much as 85 percent of data collected and made available for public inquiry said to be incomplete (CAICT 2023c). There is hope that data exchanges could solve the problem by creating an effective pathway to the safe circulation of standardized and high-quality public data, considering the sensitivities around national security, personal information protection and business secrets.

The Beijing International Big Data Exchange and the Hainan Supermarket for Data Products are both front-runners, although their models notably differ. After some initial success in the finance sector, the local government of Beijing entrusted the data exchange with managing its entire public data resources, turning government open-data platforms into marketplaces (Li 2023). The platform remains a work in progress, with most products featuring unstructured statistical data and the government’s own open-data platform still offering a greater variety for free. Tellingly, half of the listed products are credit inquiry services offered by the same state-owned financial big data company that runs the exchange on behalf of the government.9

The government-run model in Hainan is based on a larger ecosystem of actors and data developers and seems more promising. The Hainan Big Data Administration invites companies to develop products and services based on data resources made available by the local government. These data products and services are then listed and traded at the Hainan Supermarket for Data Products (Dong 2021). As a technology partner, Tianyi Cloud, a state-owned cloud service provider, desensitizes public data using PET, secure multi-party computation and federated learning.10 As of this writing, 1,070 data products and services had been developed and commercialized.11

Toward the World’s First State-Led Data Market

China is a clear first mover in elevating data to a national strategic priority and designating it as a factor of production. This reflects a uniquely state-driven approach to digital governance, which can also be seen in the high degree of government control and coordination behind the data exchanges discussed in this essay. Beijing’s push to have the state direct data circulation provides the momentum behind the ongoing reform of China’s data market, yet it may also pose the biggest obstacle to its further development. Although more private firms are joining in, China’s data exchanges are still a playground for state-owned enterprises and companies with strong government connections.

Moreover, as most exchanges are abandoning commission fees in favour of membership-based business models where users are charged a fee to access value-added services, profitability remains a question. With access to abundant capital thanks to government involvement, data exchanges can presumably afford not to be profitable for some time. However, this could become a challenge long term if the most competitive (private) tech companies continued to snub these institutional channels. China’s newly established National Data Administration will have some convincing to do, following an unprecedented regulatory crackdown led by the CAC and other agencies that burned more than US$1 trillion in market value from China’s leading tech firms, strengthened the party-state’s grip over privately held data and damaged the economy.

These developments will carry implications beyond offering lessons for other jurisdictions, considering that Chinese authorities are also exploring how some of these marketplaces could serve as gateways for cross-border data transmissions (von Carnap 2022). The Shanghai Data Exchange, for example, has pledged to align with standards outlined in the Digital Economy Partnership Agreement, which China officially applied to join. The extent to which the country will seek to integrate its data market with those of its trading partners or prioritize domestic circulation in the name of national security remains to be seen.

Authors’ Note

This essay is based on a longer unpublished paper for which research was completed in the fall of 2023. It does not consider developments after China’s National Data Administration (2023) kicked off its work and issued its first policy at the end of 2023.