The third plenum of the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is one of the most important cyclical events in Chinese politics. Plenums refer to the planned meetings of the Central Committee, the highest organ of power of the CCP, which is elected for a five-year term. The current twentieth committee serves from 2022 to 2027.

Throughout a Central Committee’s mandate, seven plenums are held, bringing together all its current

205 members and 171 alternate members. The first, second and seventh plenums typically focus on the power transition between Central Committees. The fourth and sixth plenums generally deal with party ideology. The fifth plenum deliberates over the country’s five-year development plan.

Even though plenums formally hold important powers, they are highly choreographed events only meant to approve decisions taken beforehand by the top leadership. However, the CCP often uses these occasions to signal important policy changes. The third plenum is normally seen as the most consequential, as it traditionally centres on economic issues.

Historically, this plenum has launched major transformative undertakings. For instance, in December 1978, Deng Xiaoping used this event to initiate liberal economic reforms, launching China’s economic transition to becoming the world’s second-largest economy.

Equally important, plenums are occasions for the CCP to make senior personnel changes in top government and party institutions. This offers the elite CCP cadre the opportunity to formalize purges and officially name replacements at the highest levels.

Key Takeaways

There were significant expectations for this plenum (July 15–18), as consensus is growing on the need for deep reforms to address structural problems in the Chinese economy (such as stalled economic growth, lower productivity and rising youth unemployment). Increasingly, projections indicate that China’s GDP will not overtake the United States’, given existing issues such as an ongoing property market crisis, weak consumer confidence, risks of deflation, mounting debt, ongoing trade tensions and falling foreign direct investment, as well as aging workforce demographics.

First expected to take place in the fall of 2023, this plenum was delayed for reasons still unclear.

According to most experts on China, the plenum’s concluding direction was disappointing. It was inward-focused and status quo-oriented, and myopically championed “the China-model” of export-led development. While promoting advanced manufacturing, revisions to the tax system and reduced debt risk, it indicated growth will continue to be mostly driven by state-led efforts and institutions and rely on a heavy focus on science and technology as well as innovation — deemed the engine of “high-quality development.”

Despite recent Politburo meetings leading to promises of the CCP adopting “countercyclical measures” to spur growth with more proactive fiscal and monetary policies, it remains unclear how any of the identified reform areas will materialize absent of required structural reforms. The reform program will notionally continue until 2029, but with few concrete measurables.

Implications for National Security and the Military

Major themes throughout the plenum’s summary policy document dwelled on national security issues, such as keeping key industrial supply chains safe and boosting strategic military deterrence.

President Xi Jinping remains preoccupied with what he defines as China’s “urgent need” to counter “increasing uncertainties and unpredictable factors” impacting national development. He views “external suppression and containment” by the West as continuously escalating.

Nowhere is this more true than in the maritime domain. President Xi has proven instrumental over the past decade in shaping China’s somewhat passive stance on maritime territorial issues into an assertive strategy to defend its expansive claims. For example, Xi has exerted a major influence on China’s handling of both the Scarborough Shoal and Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands’ disputes. Since at least mid-2012, he has served as the senior member of two high-level oversight bodies on maritime security issues. Moreover, Xi has reportedly personally approved a step-by-step plan to intensify pressure on Japan, thereby rejecting a more moderate approach advocated by some in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Along these same lines, the selection of Admiral Dong Jun as China’s new defence minister is a significant move, bringing a seasoned navy veteran with a deep understanding of maritime affairs to the forefront of China’s defence apparatus. As the former top commander of China’s navy, Dong played a pivotal role in advancing Xi’s vision of a modern ocean-going navy capable of safeguarding China’s interests beyond its immediate waters.

In a related sense, the term “army” (军) appears 31 times in the text, with an entire section dedicated to defence issues. That section highlights the goal of “enhancing party loyalty” in the military and “the Party’s absolute leadership over the people’s armed forces.” The heavy emphasis on political loyalty in the army is an admission of weakness from the CCP, frustrated in recent years by corruption scandals, military purges and questionable People’s Liberation Army (PLA) reforms.

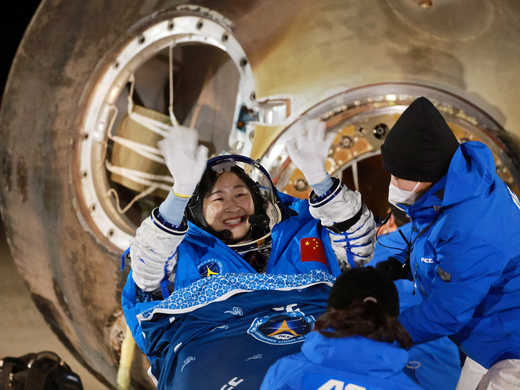

The plenum confirmed the expulsion from the CCP of former defence ministers Li Shangfu and Wei Fenghe on corruption charges. Additionally, the party credentials of Li Yuchao — former PLA Rocket Force commander — and of Li’s chief of staff, Sun Jinming, were also revoked. This was a striking illustration of the corruption problems plaguing the Chinese military, as well as the distrust from the top party leadership toward military leaders. Xi remains firm on asserting the full dominance of the CCP over the military, a feat not accomplished since the Maoist era.

Outlook

The current CCP leadership does not seem willing to address the structural problems of the Chinese economy directly, favouring instead further party control over the country and the economy. This may well undermine long-term sustained growth and fuel mounting tensions between elite factions.

This plenum was in many ways focused on the short term, with a renewed commitment to simply sustaining a five percent growth rate (which is already a drop of two to three percent from earlier norms). If China resolutely intends to reach this goal in 2024, it will require hard decisions and a robust fiscal stimulus package — more than what has just recently been announced.

Purges in the top leadership were officially confirmed, but with a surprising outcome for Qin Gang, the former foreign minister who inexplicably disappeared last year shortly after his nomination. In contrast to the situation with others who were expelled from the CCP, the Central Committee “accepted” his resignation, and he keeps the title of “comrade.” This forgiving treatment was not afforded to Qin’s military counterparts.

Moreover, unlike his predecessors, the new defence minister, Admiral Dong Jun, was neither added to the Central Military Commission nor appointed a state councillor. This is generally considered to constitute a demotion for the defence ministry and limits Dong’s decision-making authority in the PLA.

Setting long-term objectives out to 2029 is a strong indication that Xi intends to stay in power as party leader for a fourth term, with his current term ending in 2027.

Conclusion

The full impact of the third plenum, widely regarded as a disappointment, is not immediately evident. This plenum demonstrates the top leadership’s affirmation of existing preferences and a top-down vision of the economy. It masks dissenting opinions and avoids implementing actual required reforms, due to either ideological or organizational roadblocks.

It may also represent the apex of Xi’s power, as the current senior leadership (confirmed at the twentieth National Congress of the CCP) is filled with long-time loyalists with no independent basis of alternative power. An entrenched and ongoing anti-corruption campaign provides Xi with the tools necessary to target and eliminate both civilian and military rivals he deems disloyal or threatening.

The prevalence of a “security first” mindset will insulate the PLA from any possible financial cutbacks or rationalization efforts. Annual public defence budget increases of approximately seven percent (for a total allocation of US$236 billion in 2024) will continue for the foreseeable future.