Last year, Chinese President Xi Jinping stated it is entirely possible that China would double its per capita GDP by 2035 (quoted in Tang and Xin 2020). This implies average annual growth of just under five percent over the 15-year period. Maintaining such a rapid rate of growth will not be easy. Analysts point to three risks China needs to manage to avoid falling into the middle-income trap. It must ensure its debt load is sustainable, manage a looming demographic crisis and prevent productivity from stagnating. In the following analysis, we assess the gravity of these risks by situating China among the other major economies.

How Risky Is China’s Debt?

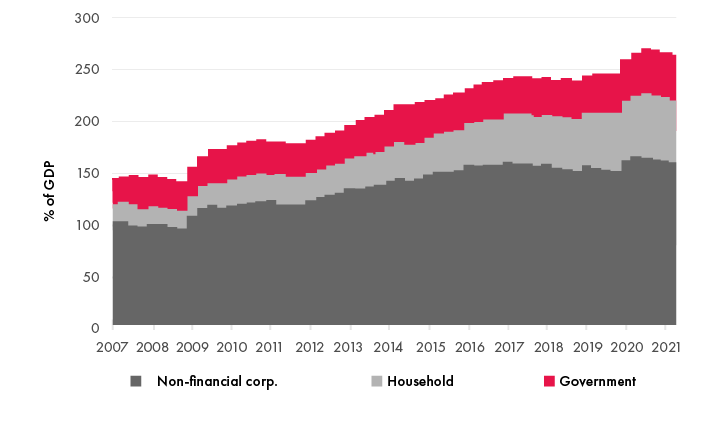

Most economists would agree that the financial stability risk posed by the steep rise in China’s indebtedness is the country’s primary macroeconomic concern (see Figure 1). The growth in China’s debt-to-GDP ratio has undergone four distinct phases since the outbreak of the global financial crisis. Between December 2007 and December 2015, it rose by more than 80 percent of GDP. About two-thirds of this debt was accumulated by corporations. Initially, most of these liabilities were incurred as part of the government’s plan to counter the depressive effects of the crisis. In subsequent years, access to credit was liberalized, as China’s shadow banking system grew in importance.

Figure 1: The Non-Financial Sector’s Macro Leverage Ratio

At the end of 2015, the authorities began to pursue a policy of deleveraging to stem the rise in debt and increase the transparency of the shadow banking system (Wu, Wu and Lin 2019). By 2017, addressing financial risks became a key priority — one of the “three tough battles” — along with alleviating poverty and tackling pollution (Xinhua 2017). Between December 2015 and December 2019, the debt of the non-financial corporate sector was essentially unchanged as a percent of GDP. Mortgage borrowing by households accounted for almost all the increase in indebtedness in this period.

The outbreak of the pandemic ushered in the third phase of indebtedness. Between December 2019 and September 2020, China’s debt rose by close to 25 percent of GDP, as the country fought to maintain employment and output. The rise in indebtedness in these nine months was larger than over the previous four years.

With COVID-19 under control and the recovery well established, the authorities again turned their attention to deleveraging and containing financial risks. Between September 2020 and June 2021, debt fell by close to six percent of GDP.

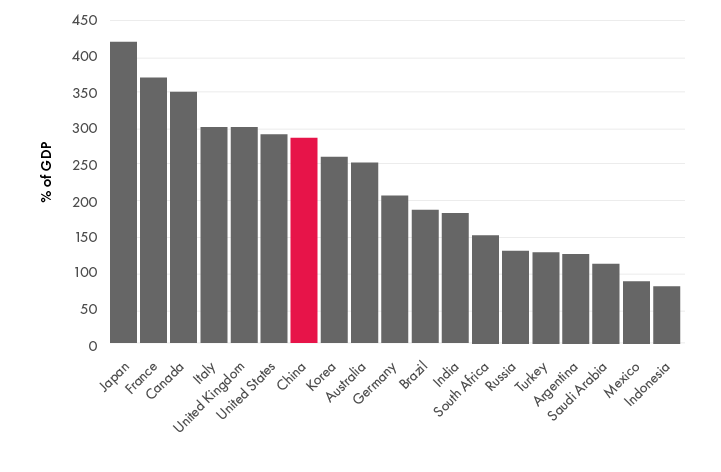

Data from the Bank for International Settlements1 allows us to compare China’s indebtedness with those of the other Group of Twenty (G20) countries. As at June 2021, China ranked as the seventh most indebted G20 country, between the United States and Korea (see Figure 2). While China’s indebtedness is clearly not “off of the charts” compared to its G20 peers, it is high for a large, middle-income country.

Figure 2: Credit to the Non-Financial Sector

The riskiness of China’s debt is mitigated by a number of factors. China’s industrial base is large and diversified, making the economy resilient to changes in demand. As an international creditor with an only partially open capital account, China is well-insulated from potentially destabilizing changes in global interest rates. Moreover, its debt is mostly denominated in renminbi and held domestically, immunizing it from changes in international investor sentiment.

Property developers’ liabilities constitute the most worrisome aspect of China’s indebtedness. We estimate that their interest-bearing liabilities exceeded 41 trillion yuan at the end of last year (Kruger 2021a). This is close to 40 percent of GDP and about a quarter of all non-financial corporate finance outstanding. It represents a risk to China’s trusts, banks and capital markets.

The authorities have, for some time, had rules around how much banks could lend to property developers and the uses to which these funds could be put. Last fall, they implemented a new framework that links the amount the developers can borrow to the health of their balance sheets. The financial stress the developers are currently facing is the result of the authorities’ resolutely taking aim at this “grey rhino.”

Is China Facing a Demographic Crisis?

On May 11, the National Bureau of Statistics of China released the results of its Seventh National Census (National Bureau of Statistics of China 2021). These once-a-decade enumerations of China’s population provide the most comprehensive picture of the nation’s demographics. Media reports focused on the slow growth in the overall population and the aging of Chinese society. They warned that China faced a “demographic crisis” (Woo and Yao 2021).

Indeed, from a macroeconomic perspective, the news was not good. The working-age population (15–59) declined from 940 to 894 million since the previous census in 2010. The five percent drop in the pool of potential workers — 0.5 percent per year — represents the loss of a key input for building GDP.

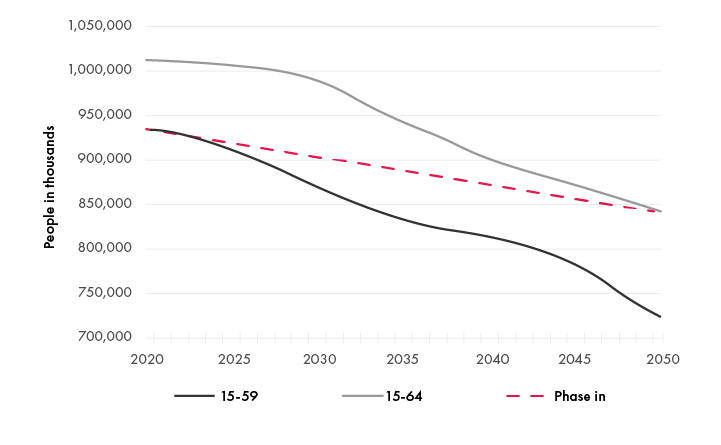

The decline in China’s working-age population is expected to accelerate over the coming decades. Projections from the United Nations indicate that between 2020 and 2050, the amount of 15–59 year olds will fall by 23 percent, or 0.9 percent per year. According to standard models, a one percentage point decline in employment translates into a fall in GDP growth of 0.55 percentage points (Herd 2020). If a constant share of the working-age population is employed, then the projected decline in the 15–59-year-old group would shave 0.5 percentage points off of annual GDP growth for the next 30 years.

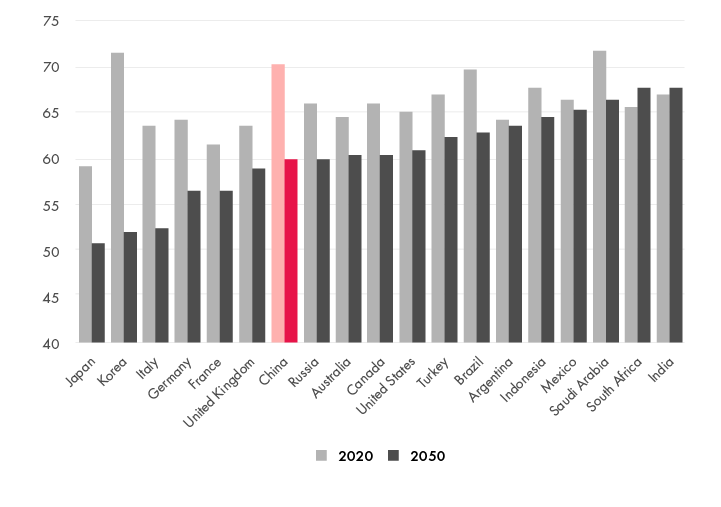

Looking at the G20 countries, we see that China is not alone in facing a shrinking workforce, although its transition is predicted to be among the most extreme (see Figure 3). In 2020, the Chinese economy benefited from a relatively high share of working-age people in its total population, ranking third after Saudi Arabia and Korea. However, by 2050, China’s ranking will fall to the seventh-lowest. Only Korea and Italy are expected to experience more precipitous increases in dependency.

Figure 3: Working-Age Population (15–64) as a Percentage of Total Population

One obvious policy response to the looming demographic decline would be increasing the retirement age. In China, female workers currently retire at 55 and males at 60. These low retirement ages appear to be an artifact of earlier times when the priority was ensuring sufficient jobs for young labour market entrants. Suppose China gradually phased in a five-year increase in the retirement age over the next 30 years, consistent with the dashed line in Figure 4. The resulting decline in the working-age population would only be 10 percent, compared to the 23 percent fall in the 15–59 age group. While raising the retirement age by five years doesn’t eliminate demographic decline, it cuts the problem by more than half.

Figure 4: Effect of Raising the Retirement Age

Providing more education is another way to manage demographic decline. The recent census showed that China’s educational attainment has continued to rise. In 2020, those aged 15 and above had, on average, 9.9 years of schooling, up from 9.1 years in 2010. Over the next 30 years, it is reasonable to expect that educational attainment will increase further. Let’s assume that the average years of schooling rises to 12.2 years by 2050. That’s where Korea is today. By comparison, Germany is at 14.2 while Canada, Switzerland and the United States are at 13.4 years.

If human capital increases one-for-one with years of education then, after 12.2 years of schooling, the average worker in 2050 would be 23 percent more productive than one today. This increase in human capital would fully offset the output lost from the declining working-age population.

Can China Innovate?

The foregoing shows why Chinese policy, for example as embodied in the 14th Five-Year Plan, emphasizes innovation. China’s high investment rate and its rapid increase in indebtedness limit the extent to which capital accumulation can contribute to growth. With the working-age population shrinking, raising productivity is the most rational way for the country to develop.

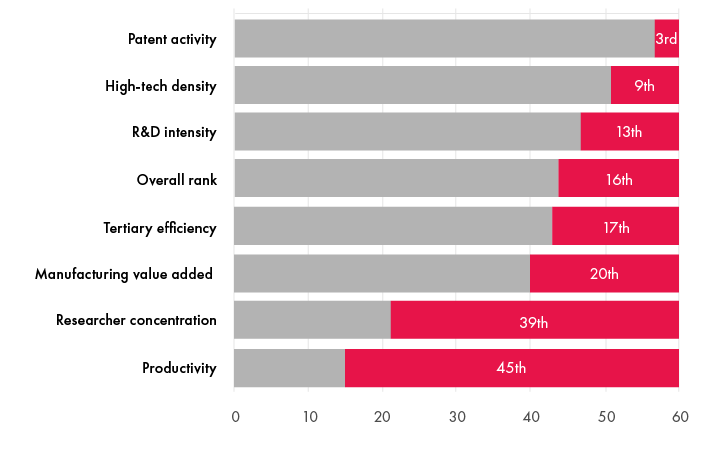

While innovation is hard to measure, Bloomberg publishes an index that tries to shed light on this problem by weighting achievement across seven elements. China ranked sixteenth out of 60 countries in the 2021 edition of Bloomberg’s index — ahead of Ireland and behind Norway (Jamrisko, Lu and Tanzi 2021). Not bad, considering China is not nearly as rich as its European “neighbours.”

In some areas, China does seem to be at the forefront of innovation. With extensive pilot projects in 10 cities (Working Group on E-CNY Research and Development of the People's Bank of China 2021), China is well-advanced in developing its digital currency (the e-CNY) (Kruger 2020). By June 30, 21 million personal and four million corporate digital wallets had been opened and the e-CNY had been used in 71 million transactions with a value of CNY34.5 billion. The e-CNY is expected to be showcased during the 2022 Winter Olympics in Beijing.

China has also been relatively quick to adopt the fifth-generation (5G) standard for broadband cellular networks (Kruger 2021b). By end-December 2020, it had installed close to 700,000 5G base stations, more than 10 times as many as the United States. China plans to install 1.4 million 5G base stations by year-end and 2.5 million by the end of 2023 (Shasha 2021). In other countries, huge upfront costs and the disconnect between the network’s social and private returns have delayed 5G development. But China has made 5G a national priority and is developing the system and applications in tandem.

President Xi has pointed to high-speed rail as an example of China’s success in independent innovation (Xinhua 2021). In its early days, China’s high-speed trains relied heavily on imported prototypes and parts. Today, an estimated 90 percent of its supply chain is made domestically.2 China’s innovations include cars on the Beijing-Harbin line that can withstand very cold temperatures (Cripps and Deng 2021). Its high-speed rail development has also led to advances in engineering with the construction of extra-long bridges and tunnels (Molitch-Hou 2019).

While China didn’t invent high-speed rail, it has made this technology its own. Its high-speed network is three times the size of Europe’s and close to 70 percent of the global total.3 Recent research shows that high-speed rail’s carbon footprint is less than one-tenth as large as that of cars or planes (UIC 2018). Thus, high-speed rail is not only a case study in independent innovation, but also a key part of China’s low-carbon future.

Notwithstanding these successes, the elements of Bloomberg’s Innovation Index point to the areas in which China might want to focus to further enhance its ability to innovate. China does well on patent filings, creating high-tech companies and spending on research and development (R&D). Its weak spots are productivity and researcher concentration (see Figure 5).

Figure 5: China’s Ranking in Bloomberg 2021 Innovation Index

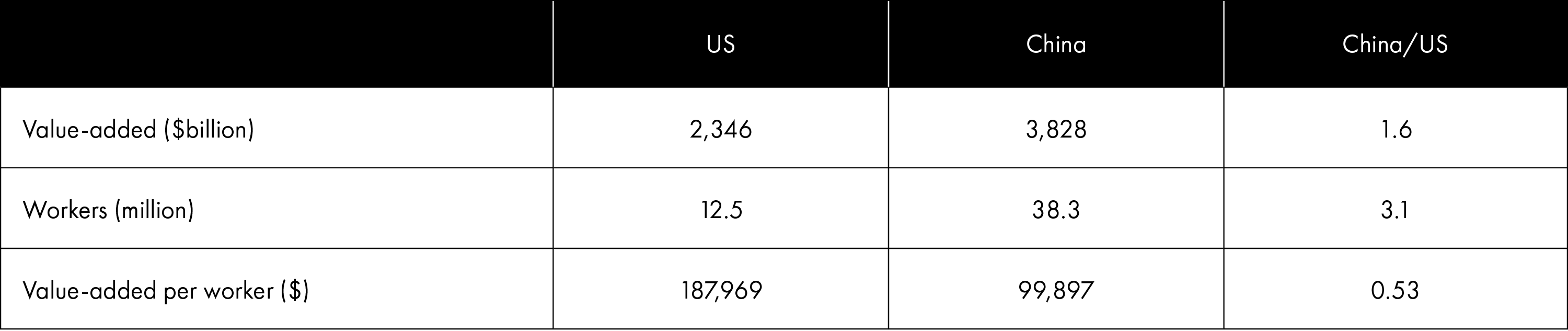

In comparing China’s manufacturing sector with that of the United States, we do find a large productivity gap. In 2019, the value-added of China’s manufacturing sector was 1.6 times larger than that of the United States (see Table 1). However, that output was produced by more than three times as many workers. So, the productivity of China’s manufacturing sector — in terms of value-added per worker — was only about half as high as in the United States.

Table 1: Manufacturing Sector Indicators (2019)

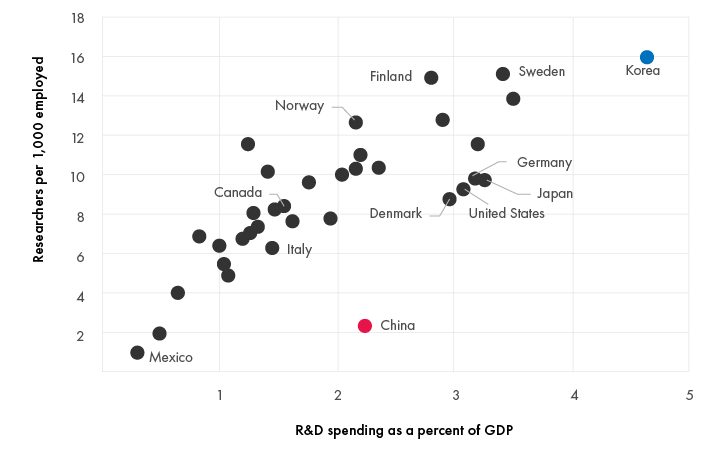

China spends a lot on R&D, but it is less successful at training scientists. Bloomberg ranked it thirty-ninth in the employment of researchers (as a share of the workforce). Given its R&D expenditures, the experience of other countries suggests that China should be engaging five times more researchers than it currently does (see Figure 6).

Figure 6: R&D Indicators (2019 or latest)

How Manageable Are China’s Risks?

China’s debt has risen rapidly, but it is not “off the charts.” The authorities have made deleveraging a priority, but shocks have knocked them off course. In the absence of further shocks, China’s debt-to-GDP ratio should, at a minimum, stabilize. Strengthening property developers’ balance sheets may not be a smooth process, but it will ultimately reinforce financial stability.

China is not unique in facing the challenge of an aging population, but it has the advantage of a strong demographic starting point. Moreover, it has options to offset the impact of falling labour supply on GDP growth.

China’s ability to double its per capita GDP by 2035 will be tied to its ability to innovate and maintain high productivity growth. As its experience with high-speed rail shows, innovation can proceed through continuous improvement as well as groundbreaking invention.