After a year of high-level diplomacy, relations between China and the West are no longer in free fall. Yet China’s somewhat warmer outward posture belies its becoming a more closed society at home. President Xi Jinping’s predecessors anticipated the country’s so-called great rejuvenation would be attained through economic growth. Xi, by contrast, believes that if China is to realize its ambitions as a global superpower, national security is paramount. Threats both foreign and domestic, real and perceived, must be confronted.

But the country’s once galloping economy — the long-standing source of legitimacy for the ruling Chinese Communist Party (CCP) — has slowed. And cracks in Beijing’s governance model are emerging. As China faces an array of internal problems, state censorship has been ratcheted into overdrive. Wary of espionage, Beijing is taking ever more extreme measures to restrict information flows. This matters not just for China’s 1.4 billion citizens, but also for the rest of us. A more opaque China could aggravate ignorance and impair decision making about its actions within the global economy and international order.

Accessing knowledge and diverse perspectives in modern China has long been challenging. The CCP has positioned itself as the primary arbiter of political, economic and social life since the People’s Republic of China was founded in 1949. There has never been press freedom. By strictly curbing expression, the party ensures it retains its monopoly on power.

But the suppression of information has gotten progressively worse since the COVID-19 pandemic. More than four years since the outbreak began, China’s government continues to stonewall attempts to determine the virus’s origins. Beijing’s draconian zero-COVID policies also created a blueprint for authoritarian states to restrict civil liberties under the guise of public health measures.

Geopolitical rivalries are contributing, too. In a lecture broadcasted during the CCP’s twentieth National Congress in October 2022, Xi warned that “external attempts to suppress and contain China may escalate at any time.” The gathering also served to showcase the Chinese leader’s consolidation of absolute control over his party. Loyalists were rewarded with cabinet positions, sidelining any viable opposition to Xi’s policies.

Since then, government officials have raided the offices of several foreign companies, allegedly for stealing state secrets. Some businesses have been forced to shutter operations entirely. Most of those targeted were consulting and due diligence firms that gathered information about China that was useful for external investors. Others helped multinational businesses set up local operations or branch locations in China. In the meantime, sweeping reforms to Beijing’s state secrets law took effect on May 1. Among the notable changes to the legislation were vague new rules that make the sharing of “work secrets” a punishable offence. National security legislation imposed on Hong Kong by Beijing in 2020 was broadened early in 2024 as well. Doing so has further hammered the city’s once-proud reputation as an enclave for journalists and a commercial gateway to mainland China.

The presence of hundreds of millions of closed-circuit television cameras equipped with high-powered facial recognition software already makes anonymity in public spaces impossible.

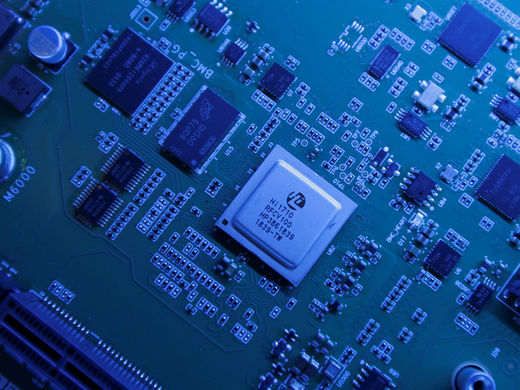

China’s Ministry of State Security announced in February that it would start monitoring outbound data flows more closely. This move reportedly includes information around plane tracking, weather monitoring and users’ pinned map locations. China’s data security law, passed in late 2021, already empowers Xi to unilaterally shut down tech firms guilty of “mishandling” what’s deemed “core state data.” One year earlier, iconic self-made business leader Jack Ma, founder of tech giant Alibaba, disappeared for months after he criticized Chinese regulators in a speech at a conference in Shanghai — remarks that prompted authorities to cancel an enormous initial public offering for his financial services company, Ant Group. Ma eventually resurfaced in March 2021, first via photos posted of himself on luxury vacations abroad. Evidently chastened, Ma has since taken up several prestigious academic postings and shied away from publicly commenting on government policy.

China’s digital surveillance apparatus continues to evolve as well. The government is effectively rewriting China’s social contract on the premise that abolishing privacy will improve service delivery. The presence of hundreds of millions of closed-circuit television cameras equipped with high-powered facial recognition software already makes anonymity in public spaces impossible. Shanghai alone is estimated to possess some 5,000 cameras per square mile. The Chinese state is also encroaching further into personal communications. Apple, one of the few Western tech companies allowed to operate in the country, was recently ordered to remove WhatsApp and the Meta-owned Threads app from its App Store.

In addition, the country’s internet regulator has started promoting its own chatbot: Chat Xi PT. Released in May, it parrots the writings and personal Marxist-Leninist philosophies of China’s president. Known as Xi Jinping Thought, the dogma is an apparent fusion of political ideology and state religion. Studying and gaining certification in it has been compulsory for years for many different groups — from university students, journalists and bankers to civil servants and employees at state-owned enterprises.

Beijing also recently resurrected a low-tech, Mao-era tactic to monitor its citizens: a nationwide network of party informants who report to police on citizens’ everyday activities. Authorities assess and grade subjects — students, neighbours, businesses — using a colour-coded system, designating them as green (trustworthy), yellow (needing attention) or orange (high risk).

In some ways, this is a natural evolution. The CCP severed China’s ties to the outside world for decades when it first came to power. The party also views the Soviet Union’s piecemeal liberalization in the late 1980s under Soviet Communist Party leader and eventual president Mikhail Gorbachev as a fatal error that triggered the Soviet collapse.

And biographers argue that Xi’s priorities are driven by his personal history as well. As the son of a senior CCP propagandist who was purged during the chaos of the Cultural Revolution, his formative years took place during a time of traumatic national upheaval. The experience apparently imprinted on him an overriding desire for party discipline and social order.

But the crackdown on free expression also appears to stem from China’s diminished economic trajectory. A property sector crash, birthrate crisis, trade frictions, plummeting foreign investment, the ballooning debt of local governments and struggles to transition to a consumer-based economy all have taken a toll. Youth unemployment hit 21 percent in August 2023 before the government’s statistics agency stopped releasing such data. Responding to rumbling criticisms last year, Xi told frustrated citizens to learn to “eat bitterness.” (He has since softened his tone, calling for the creation of more high-quality jobs for graduates.)

CIGI’s recent global outlook analysis projects that China will no longer overtake the United States in terms of leading economic influence before 2040 — if ever.

Beijing is gambling that increasing state support for high-end manufacturing exports can jumpstart China’s economy, particularly with items needed for the green energy transition. This was reflected in announcements coming out of the CCP’s recent third plenum held from July 15-18. The major, closed-doors party gathering, held twice a decade, is meant to shape China’s social and economic policy goals for the next five years. “A liberalized economy with charismatic entrepreneurs and an open flow of information to create ecosystems of different industries is just not [Xi’s] priority,” political scientist Michael Beckley argued in an online debate with Chinese economist Keyu Jin in July 2023. “That’s why he's prioritizing the real economy of heavy industry."

But this strategy is far from airtight.

For starters, sanctions and tariffs are piling up. The United States in May 2024 announced 100 percent tariffs on Chinese electric vehicles (EVs), citing Beijing’s massive subsidies for its auto industry. The European Union in early July unveiled provisional levies on Chinese EVs, which could start to be imposed by the end of the year, pending an ongoing investigation. Canada on August 1 will conclude its public consultations on similar measures. Developing countries, such as Brazil, India and Turkey, are also concerned about China’s market-distorting practices. Moreover, export revenue, should it increase, can do little to improve domestic consumer confidence in China. Nor can it prop up the crumbling property sector, comprising a third of China’s economy.

Should Xi’s plan falter, China’s restless citizenry will likely find ever more creative outlets for dissent.

In February, Chinese netizens flooded a social media post about wildlife conservation on the US embassy’s Weibo page with more than 165,000 comments slamming a US$7 trillion drop in value of the Shanghai Stock Exchange. During pandemic lockdowns, a Chinese student studying abroad used his X account (then Twitter) to crowdsource and repost acts of dissent in China under the avatar of a cartoon cat. The China Dissent Monitor, a project of the US-based democracy watchdog Freedom House, similarly compiles data and visual highlights of civil disobedience across the country. The use of virtual private networks is increasingly popular. And, most recently, Chinese youths are pushing cultural boundaries through the use of jailbroken AI chatbots. Digital activists are also diligently storing Chinese internet archives outside the country to avoid content being lost to censorship or server disconnection.

Turning the world’s second-largest economy around will take time. Meanwhile, Beijing is expected to crack down ever harder on civil society. Ironically, this will make it more difficult for the government to accurately assess the situation within its own borders. By creating an autocratic echo chamber of “good” news, Beijing will only further limit its capacity to bring effective reform.

Make no mistake: the Chinese state is nowhere near a risk of collapse. “Authoritarian regimes can fail at almost everything so long as they suppress all other political alternatives,” historian Stephen Kotkin cautioned recently. For evidence, one need only look to China’s geopolitical allies in Iran, North Korea and Russia.

Yet China can never be simply another authoritarian state — it is the top trading partner for more than 120 countries. Its internal discourse and dynamics matter greatly because its policies affect the entire world. In his book, New Cold Wars: China’s Rise, Russia’s Invasion, and America’s Struggle to Defend the West, veteran journalist David E. Sanger offers a blistering critique of Western strategic thinking. The West’s assumption that China’s economic integration would bring liberalization is the most egregious intelligence failure of the twenty-first century, Sanger believes. He’s not wrong.

Wherever fault may lie, the contours of globalization and geopolitics are being reshaped. China is now spearheading efforts to move international systems away from liberal democracy. This presents great risk. Richard Haass, the long-time president of the Council on Foreign Relations, has rightly remarked that, to provide global leadership, great powers must be “predictable and reliable.”

Instead, China is by increments becoming an autocracy supported by a cult of personality. Historically, such systems of government have tended to be neither predictable, nor reliable.

A version of this piece first appeared in SpaceNews.