After more than five years of intensive design work, the People’s Bank of China (PBOC) has started to pilot its digital currency. In southern Shenzhen, eastern Suzhou, mid-western Chengdu, and northern Xiong’an, public servants and employees of state-owned institutions are receiving a small amount of their remuneration in the digital renminbi, which can be spent at a host of retail stores and restaurants.

The PBOC is hardly unique among central banks in working to develop a digital currency, but it is one of the most advanced. According to a survey carried out by the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) late last year, while 80 percent of central banks are engaged in some sort of digital currency research and development, only 10 percent have progressed to pilot projects. Moreover, 70 percent of the banks say that they are unlikely to issue digital currencies, even in the medium term.

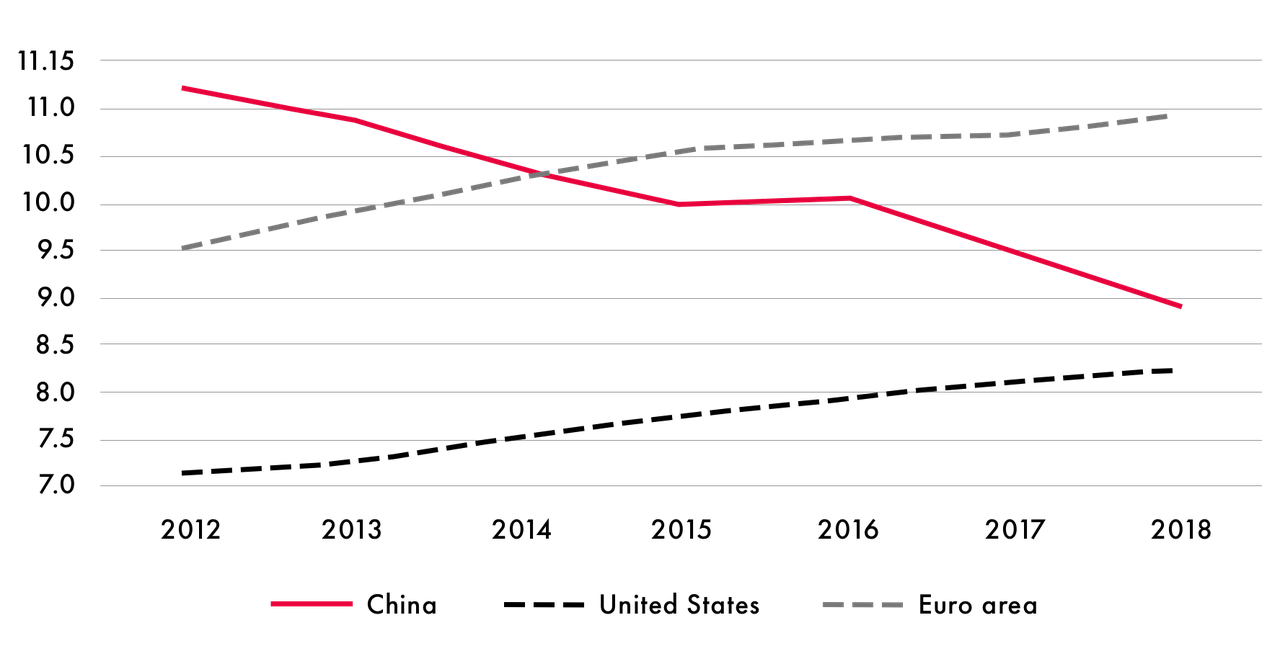

The PBOC is being motivated, in part, by rapid domestic financial innovation, which has led to the declining use of cash. Data from the BIS shows that the ratio of banknotes and coins in circulation to GDP is rising in the United States and the euro area. However, it is falling sharply in China, where consumers are abandoning cash for mobile payments made via their cellphones (Figure 1). China’s mobile payment infrastructure has become particularly well developed. The two dominant platforms — Alibaba’s Alipay and Tencent’s WeChat Pay — had 890 million users in 2018.

Figure 1: Banknotes and Coins in Circulation (as a % of GDP)

As a Chinese resident, having downloaded the two companies’ apps and linked them to my credit card, I use my phone to shop anywhere, from upscale malls to street vendors. All I need to do is scan the ubiquitous Alipay or WeChat Pay QR codes and enter the purchase price. Almost immediately, a mechanized voice informs the vendor that a purchase of a particular amount has been made. I really never have to carry cash. Indeed, I see far fewer automated teller machines in Chinese cities than in their North American and European counterparts, because there is really no need for people like me to refill our wallets with bills.

The rise of mobile payments has meant greater convenience for consumers, but it has been an even bigger boon for Chinese merchants, especially the smaller ones. Consider Mrs. Ma, who makes delicious Shandong-style savoury pancakes (a typical breakfast snack) at her street-side stall by my local subway station. Mobile payments allow her to continue serving the queue of commuters without having to take off her cooking gloves and count change. Indeed, most of her customers have already scanned her QR code before they arrive at Mrs. Ma’s griddle to tell her whether they want hot sauce, spring onions or lettuce on their pancakes. Mrs. Ma no longer has to spend time managing her cash. She need not worry about the risks of theft or loss, as her sales have been instantly credited to her Alipay and WeChat Pay accounts.

Given how well the existing system of mobile payments works for China’s consumers and vendors, why is the PBOC keen to issue its own digital currency?

First, a digital renminbi could stem the loss of seigniorage that arises from the decline in the use of cash. Second, it could mitigate the competitive and operational risks involved with having two private companies process a large and growing share of China’s retail payments. Third, it could enhance financial inclusion. Anyone who lacks access to the Alipay and WeChat Pay platforms — for example, the elderly, residents of rural areas and visitors from overseas — can run into problems paying with cash or credit cards. Indeed, in 2018, the PBOC had to crack down on retailers who refused to accept cash.

While 80 percent of central banks are engaged in some sort of digital currency research and development, only 10 percent have progressed to pilot projects.

The PBOC’s work on the digital renminbi is also likely motivated by the advent of cryptocurrencies and Libra. It sees the digital renminbi as an issue of national currency sovereignty and wants to assume a leading role in digital currency development rather than play catch-up to innovation taking place elsewhere.

The digital renminbi is centrally managed and account-based. It is not a decentralized token system like bitcoin. Nor is it blockchain-based, as blockchain technology cannot keep pace with China’s tremendous volume of mobile payments.

The digital renminbi is designed to leverage the existing mobile payments infrastructure and is not being set up as a parallel system. Individuals need not open new accounts; they simply download the digital wallet app to their cellphones and link it to their bank cards. Their financial institutions, who will have bought the digital currency from the PBOC at 1:1, provide them with the digital renminbi by debiting their bank accounts.

The PBOC is being careful to ensure that the digital renminbi has a minimal impact on monetary policy and financial stability. Financial institutions will have to provide 100 percent backing to use the digital currency. This backing ensures that no additional money is created, and that the digital renminbi remains the liability of the central bank. The PBOC has stressed that the digital renminbi is essentially a digital banknote and it will not pay interest. An interest-bearing digital renminbi would have the potential to lead to disintermediation, as consumers could move out of interest-bearing bank deposits for the more convenient mobile currency. Such disintermediation could force the banks to raise interest rates to retain depositors. However, keeping funding costs low and stable is an important consideration in China, where small banks typically have challenges in raising deposits.

Given how well China’s mobile payment system is already working, will there really be a demand for the digital renminbi?

The digital renminbi offers three advantages compared to the existing mobile payment system: lower cost, greater anonymity and reduced reliance on the internet.

Merchants like Mrs. Ma are charged volume-based fees for her customers’ use of the Alipay and WeChat Pay systems. Moreover, while she can freely use the balances of her Alipay and WeChat Pay accounts to purchase goods and services, Mrs. Ma would be charged an additional fee should she wish to take them outside of their systems, for example, to deposit these balances in her bank. In contrast, no fees are associated with the use of the digital renminbi, just as with any other form of cash.

Currently, consumers must provide personal information in order to access the Alipay and WeChat Pay payment systems, but the digital renminbi will provide for “controllable anonymity.” Small-value transactions will be, essentially, anonymous. However, the PBOC is looking to strike a balance between the public’s desire for privacy and the need to prevent money laundering, terrorism financing and tax evasion. This will be done by limiting the size of the digital wallets and setting limits on the value of transactions that can be made in the absence of providing personal identification.

The Alipay and WeChat Pay systems typically rely on internet connections — either Wi-Fi or cellular — to connect a credit card to the vendor’s account. While the digital renminbi app allows the full range of payment options currently available through Alipay and WeChat Pay, it also permits a Bluetooth-enabled transfer of funds that will not depend on internet connectivity. Alipay and WeChat Pay permit users to load money from their bank accounts on to their phones and pay via Bluetooth, in case internet connectivity is lost. As there is a cost to re-depositing these funds, transaction balances on phones are typically kept low. In contrast, users of the digital renminbi would not incur such transaction fees and one could imagine that they would carry larger balances.

The digital currency could accelerate the internationalization of the renminbi. In addition to addressing the domestic concerns noted above, there is potential for it to be the platform of choice for small, cross-border payments. Remittances are incredibly expensive; for example, a recent report by the World Bank estimates that it currently costs US$13.58 to remit US$200. With the digital renminbi, the cost of remittances would essentially fall to zero.

PBOC Governor Yi Gang has emphasized that the digital renminbi has not yet been officially issued and that there is no timetable for its full rollout. However, he recently suggested that further piloting could take place at the 2022 Beijing Winter Olympics — a perfect environment for foreign visitors to test China’s digital currency.