he 2020 COVID-19 pandemic has once again brought into focus the problematic nature of the Canadian Armed Forces’ (CAF’s) domestic role. For many weeks, more than 1,700 members of the CAF were on duty in long-term care homes while another 22,000 CAF members were put on standby. Over the past decade, Canada has become more reliant on the CAF to respond to domestic emergencies, which are growing in frequency (see Table 1). The CAF participated in 30 missions between 2011 and 2020 compared to six between 1990 and 2010, and 10 weather-related missions in 2017–2018 versus 20 between 2007 and 2016, but only 12 such missions between 1996 and 2006. In 2018, the chief of the defence staff testified before the Standing Committee on National Defence: “It’s now almost routine. We have, I think for the last three years, deployed to support provinces in firefighting and managing floods. It’s now becoming a routine occurrence, which it had not been in the past. We take that into consideration in terms of the force structure and employment of the reserves.” As taskings have become fairly predictable (March to April for floods; July to August for wildfires), the CAF, in particular the Army, has minimized disruption by building these assignments into its annual planning cycle.

Yet in December 2019, the commander of the Canadian Army cautioned: “If this becomes of a larger scale, more frequent basis, it will start to affect our readiness.” CAF leaders would like to see the armed forces’ combat role preserved. But just because the CAF has curated an image of itself as an expeditionary force to be deployed abroad, need it always be that way? Is combat necessarily the overriding role of the CAF? CAF leaders emphasize the armed forces’ combat role, but politicians are looking for a better return on their investment of about $22 billion annually in defence. As humanitarian assistance and disaster relief (HADR) taskings become more frequent, what are the real costs and benefits to the CAF?

Some defence and security analysts want the HADR role to be removed from the CAF — or at least from the Regular Force — and assigned to the reserves or to a new federal agency expressly designed for this purpose. Reservists fill a HADR niche: present in their communities, they are primarily general-purpose forces, although a few Canadian Army reserve units are being repurposed for more specialized capabilities as part of the Strengthening the Army Reserve strategy. But are reservists well postured for this mission? The changing frequency of deployments, the nature of the missions and the required resources suggest that the logic that has informed the CAF’s priorities of combat versus HADR for the past 75 years may need to be reversed. How should the military and government react to greater demand for HADR? HADR is a core military role, albeit a non-traditional application of military power. This essay examines the operational content of HADR taskings since 1997 and makes a number of recommendations that include making policy changes to mitigate disaster risk, clarifying CAF roles, and determining how best to use federal funds to source disaster requirements for large contingents of semi-skilled and unskilled labour.

The CAF and Its Domestic Role

It should come as no surprise that commentators close to the armed forces — let alone the military — would try to fend off an increase in the domestic employment of the armed services. The CAF has vehemently resisted anything other than a combat role since the late 1950s when the Diefenbaker government, appalled by estimates of what a nuclear war could do to Canada, instituted a “national survival” program — and gave it to the Army to run. The program was a dismal failure. Both the Regular Force and the reserves, which were supposed to implement the Special Militia Training Program, disdained the mission while the government underfunded it. The CAF has since reacted negatively to then Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau’s inclusion of a “national development” role in the 1969 defence policy statement; the 1994 Canada 21 Council’s force structure suggestions, which were deemed as turning the CAF into a “constabulary force”; and attempts by the chief of land staff in the later 1990s to reassign militia combat arms units to logistics and combat service support. The opinion of many was that Chief of the Defence Staff Rick Hillier had reversed these trends and restored the combat focus of the CAF. This record does not bode well for growing the CAF’s domestic role.

The CAF’s concern around employment in HADR is as much about the perceived consistency of the role itself with the mission and combat orientation of the armed services as it is with any mechanics or costs of its actual implementation. Since military culture is slow to change, ready acceptance of a wider domestic role should not be taken for granted. Assigning the HADR role exclusively to the reserves, for example, would likely elicit a visceral reaction from reservists. The reserves, especially the Army Reserve, have campaigned continuously for their place as combat arms in a mobilization role. In the opinion of many reservists, they have been ignored by defence bureaucrats and treated as second-class citizens by the Regular Force. The reserves’ bitter opinion on the subject is summed up at length in a 2019 book aptly titled Relentless Struggle. While a shared HADR role may be conceivable, an exclusive one is likely to meet with stiff resistance. In addition, assignment of the HADR mission to the reserves without first addressing long-standing and serious problems with recruitment, training beyond a basic level and retention is highly unlikely to generate a reliable force.

Demand for HADR

Drawing on the CAF’s current operations list and other sources, Table 1 lists 31 HADR operations from 2010 to 2020, including the assistance activity for 23 operations, the number and type of troops assigned for 29 of them, and the duration of the operations for 23 of them. Several patterns emerge:

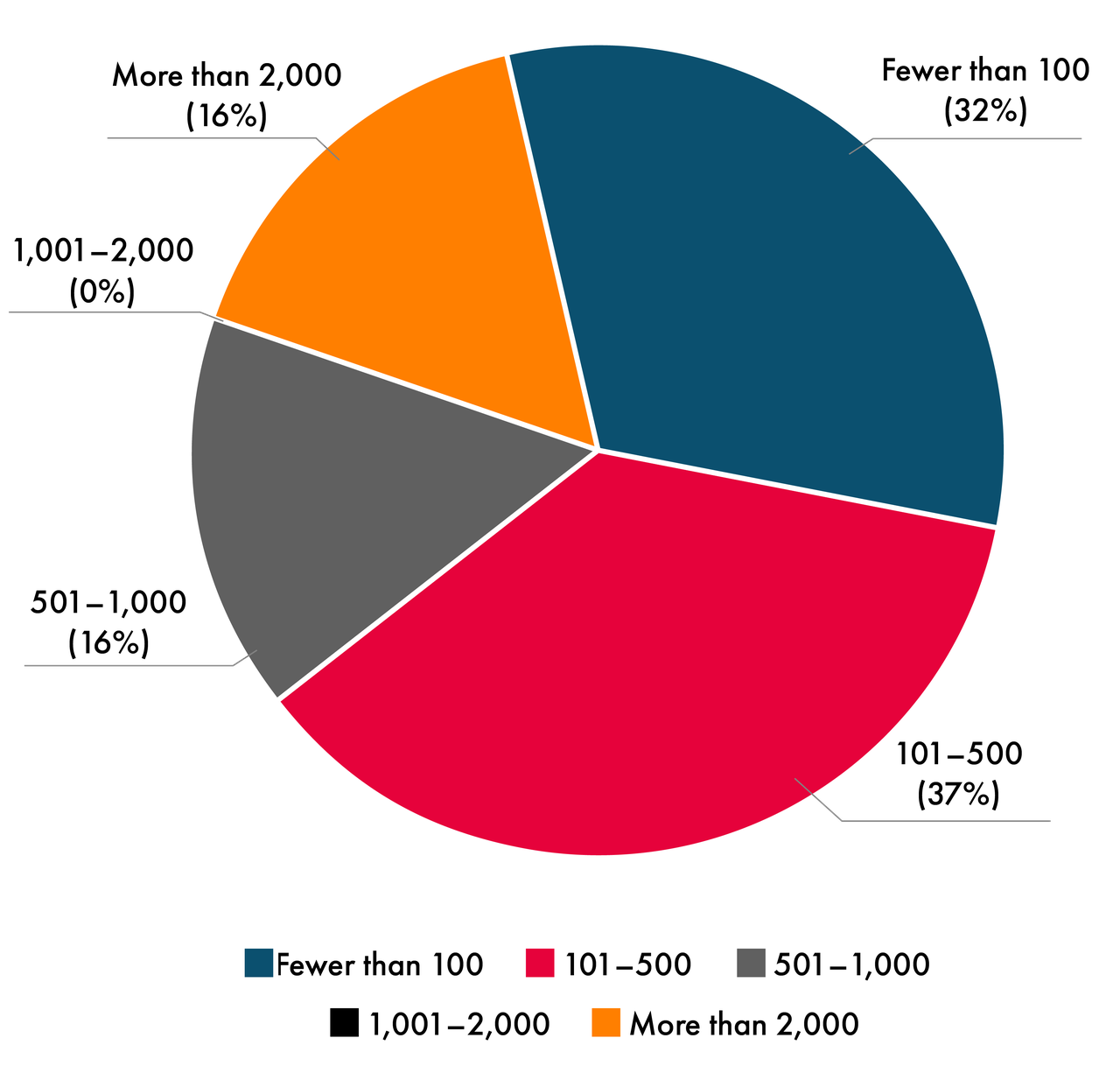

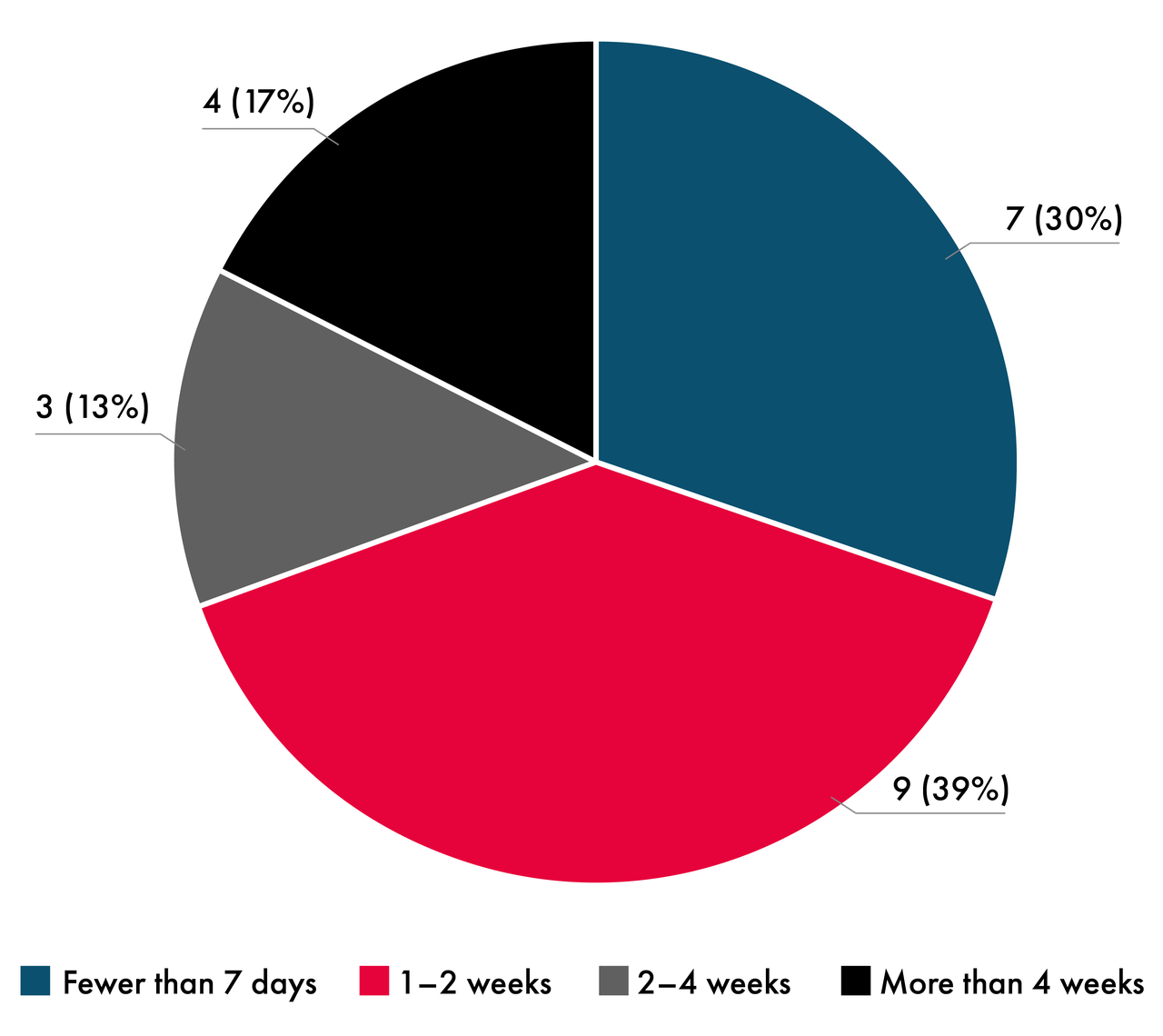

- Although the frequency of these operations is increasing, 32 percent were minor, requiring fewer than 100 CAF personnel (see Figure 1), and 16 out of 23 operations for which information is available were short (less than a fortnight in duration) (see Figure 2).

- While the size of operations has increased recently, post-2000 floods have required call-outs of about 2,500 CAF personnel, whereas the 1997 Red River floods required 8,000 personnel and the 1998 Eastern Canada ice storm required 12,000 personnel.

- Transport aviation to evacuate communities and airlift relief supplies and personnel is in high demand. There has been some demand for specialists such as engineers and a great demand for general labour to fill sandbags, evacuate victims and alert neighbourhoods by visits.

Figure 1: Operation LENTUS, 2010–2020, Number of Personnel Deployed

Figure 2: Operation LENTUS, 2010–2020, Number of Deployments by Duration

However disruptive, these operations should be well within the capabilities of the CAF. As climate change is likely to increase the frequency of wildfires and floods, demand for HADR is expected to increase apace.

Operation LASER, the CAF’s response to the pandemic, reinforces the trend toward dependency: more than 1,700 troops were deployed for more than two months across two provinces. Although CAF members were as pleased to support their country as citizens were grateful for their assistance, the question of whether their deployment represents sound policy remains. The CAF’s initial reports on Operation LASER show an overwhelming need to address relatively straightforward care management weaknesses that better inspection and more aggressive remedial action by the provinces could have averted. Indeed, better systems elsewhere explain why the CAF had to backstop only a few long-term care facilities.

The Emergencies Act sets out the overall management structure for the federal response. The provinces have primary responsibility, and any federal government backup is to be coordinated through the minister of public safety, who, under the act, is responsible for coordinating the Federal Emergency Response Plan (FERP). The premise of the Emergencies Act and the FERP is that the military is supposed to be called upon only when demand exceeds provincial capacity. Yet provinces have come to view the CAF as their first resort, rather than their last. In three recent cases, the provinces drafted and gained approval of requests for assistance before their own resources were exhausted. Newfoundland has disbanded its emergency measures organization altogether, further increasing its dependency on the federal government. Should the armed services have to deploy overseas in a crisis, CAF resources might well be unavailable for HADR. Just because the CAF is capable, it is not necessarily the optimal provider for emergency assistance. Much of the requirement appears to be for general labour for which the armed services are a (very) expensive source. Three inferences follow.

First, the trend of requests for assistance being made by the provinces and approved by the federal government before provincial resources have been exhausted is disconcerting. However, this is more a political problem than a policy one: it is hard for federal ministers to say no to provincial premiers and easy for them to reach for the most visible (and possibly sole readily available) federal resource.

Second, the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) should continue to be the go-to source for HADR aviation assets. A separate fleet of federal government aircraft on standby would be inefficient and costly. In the case of evacuating northern and First Nations communities faced with fire or flood, the obvious choice is a combination of military aviation with resident Canadian Rangers handling ground coordination.

Third, the expectation and requirement for the armed services to become involved in overwhelming disasters such as the 1997 Red River floods and the 1998 Eastern Canada ice storm is unequivocal. Events of this magnitude call for all hands on deck.

HADR in a Whole-of-Government Context

The CAF has a well-defined responsibility for HADR in federal policy. The defence policy statement, Strong, Secure, Engaged (SSE), reiterates the long-standing policy that the armed services have a role to play in domestic HADR. The SSE identifies disaster assistance as one of the eight “core missions” of the CAF. The policy vision is for a Canada that is “strong at home, its sovereignty well defended by a Canadian Armed Forces also ready to assist in times of natural disaster, other emergencies and search and rescue.” On the one hand, our analysis indicates that demand for the CAF’s HADR assistance is highly likely to persist and possibly increase without mitigation of wildfire and flood risks. On the other hand, our analysis raises three problems to be addressed.

The first is how to address the moral hazard created by the federal government backstopping provinces that underinvest in emergency response capabilities and then call prematurely for federal assistance. While the federal government can technically recover CAF deployment costs from the provinces, the optics of doing so are politically problematic, especially in the aftermath of a disaster, and especially in provinces with limited or deteriorating fiscal capacity. The federal government’s best option is to incentivize provinces proactively to plan for the consequences of climate change and create appropriate emergency response capabilities. The deployments in Table 1 show that floods impose disproportionately onerous HADR demands on the CAF.

Just because the CAF has curated an image of itself as an expeditionary force to be deployed abroad, need it always be that way?

The second problem involves levelling asymmetries associated with implementing the FERP. The CAF differs insofar as it is among the few federal departments with significant operational resources; other departments and agencies operate almost exclusively at the tactical and strategic level. More frequent HADR interdepartmental tabletop exercises, as well as greater familiarity with and expertise in the FERP, may smooth implementation. Expertise and practice aside, inadequate resourcing of the civilian emergency management function in the federal government also seems to be a habitual problem.

The third problem is how to surge general or semi-skilled labour in an emergency. This requirement is especially disruptive to the armed services’ combat training and readiness. If not the CAF, then what should be the source of this labour and what should be the federal role in maintaining it? There are four basic models Canada could follow.

The first is an alternative civilian organization. However, without a dedicated “day job” to occupy (most of its) idle time, an agency such as the US Federal Emergency Management Agency turns out to be quite inefficient: large, bureaucratic, expensive and not very agile. Still, a variant of such an approach may have merit in light of the SSE, which stresses the implications of climate change. As the federal government, along with the provinces and municipalities, develops a strategy to deal with climate change, this could precipitate the creation of new civilian capabilities or a redesign of the CAF’s structure, which could be budgeted and planned. The former might entail a federal government corps of individuals with specific skills and expertise to assist communities in preparing for, mitigating and responding to the disruptive effects of climate change, such as through controlled burns to mitigate the risk of wildfires, waterway engineering to reduce the risk of flooding and so forth. The latter would likely entail some reprioritization of the amount of time, effort and importance given to preparing for major combat.

Second, the federal government could mobilize volunteer and skilled labour, but this raises a host of legal issues. By contrast, the CAF can respond expeditiously with no additional legal liabilities. Moreover, experiences with both the National COVID-19 Volunteer Recruitment Campaign and the long-standing CANADEM International Civilian Response Corps suggest that the federal government has neither the jurisdiction nor the comparative advantage to manage centrally what amounts to a local human resources optimization and distribution problem.

Third, in anticipation of potential scarcity in the CAF’s HADR support in the event of large and urgent international defence commitments, the federal government could incentivize modest emergency services organizations at the provincial or regional level, akin to the State Emergency Service in Australia and the Technisches Hilfswerk in Germany. In contrast to provincial emergency management organizations, which have no operational capacity, emergency services organizations in other federations have a small bureaucracy whose main mandates are emergency preparedness, emergency response and after-action reports on future risk. These organizations maintain a large roster of skilled and general labour to surge on short notice and position select heavy equipment. Since these two functions impose the greatest burden on the CAF precisely while being the least optimized to respond, this would seem like a more effective, sensible approach than to task the reserves with domestic HADR or for the federal government to establish a stand-alone emergency management agency.

Finally, the best option may be for the federal government to reprioritize, along with a slight formal expansion of the CAF, to support its domestic role: create a combined capability of about 2,000 Regular and Reserve Forces soldiers to focus on improving infrastructure in remote First Nations communities. This combined force would spend most of the year liaising, planning and preparing to deploy to the community in the summer, which could be postponed or rescheduled if they were called out to a flood or wildfire instead. Such a dedicated domestic role has precedent: in the 1920s, 1930s and postwar period, the RCAF was tasked with mapping and charting Canada. During this process, the RCAF generated skills and planes for bush pilots. Only twice since World War II has the CAF had to reprioritize for major combat: the Korean War and the war in Afghanistan. The case can thus be made to reverse the logic from seeing HADR as disrupting normal CAF planning and activities to actual combat tasking being a plausible but unlikely disruptor.