Thirty-five years ago, by an act of Parliament, the security service of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) was replaced by a new civilian spy agency: the Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS). For years, the Mounties’ domestic intelligence branch had been flouting the law by using investigation techniques such as illegal break-ins, the forging of documents and the unauthorized opening of mail. As a result, in 1981 a federal royal commission recommended the creation of a new body altogether, one responsible for gathering intelligence, investigating threats to the security of Canada and reporting on those threats to the government.

On July 16, 1984, CSIS was born. Many of the officers that made up the workforce of the new agency were plucked from the RCMP, so in the early days, and for some time afterward, the culture at CSIS remained one “strong on testosterone,” as a veteran of the organization described it to me.

Three-and-a-half decades on, CSIS still draws criticism in the press, including accusations of unlawful behaviour, but when it comes to gender equality, the situation has certainly improved. According to the 2018 CSIS Public Report, women make up 48 percent of the organization’s 3,200-strong workforce and 40 percent of its senior management. Five out of 10 members of CSIS’s senior-most executive team are women.

Late last year, a small group of female employees got together and put out a call to gauge interest in a service-wide Women’s Network (while these are common in other government departments, CSIS has never had one). Almost 200 people showed up to an initial meeting, many of whom had worked in the building for decades but had never met. The network, open to both men and women, was officially launched earlier this year on March 7 — the day before International Women’s Day — and will aim to help promote diversity of thought, address gender stereotypes and unconscious bias, and provide networking opportunities and a formal mentorship scheme.

“What we believe the network is going to do is set the stage to address natural and organizational barriers, and to harness the talent of the women in our organization,” Tahera Mufti, CSIS’s head of public affairs and one of the co-chairs of the Women’s Network, told me when we met for an interview over lunch this past April in Ottawa.

She noted that it’s impossible for CSIS to fulfill its mandate of protecting Canadians and countering threats from all angles without drawing on skills that can only be offered by a diverse workforce. “We need to reflect the community that we’re protecting,” she said. “It’s no secret that women globally have joined terrorist organizations. I don’t want to say it’s best that a woman counters that, but…you can’t counter it if you’re only hiring and recruiting and promoting one type of person.”

One of the goals of the network is to break down siloes between departments and provide an environment where staff who might not otherwise meet can network with each other. Given the secretive nature of security and intelligence work and CSIS’s “need-to-know” environment, collaborating across departments and sharing best practices can be tricky, so Mufti says she was pleased and surprised by the varied roles of the women who attended the network’s first exploratory meeting.

“I thought all these women were going to be in HR and communications, and they’re not,” she said. “We are in the streets, we are surveilling, we are doing all the technology, doing all the science…we are absolutely integrated.”

When Mufti started at CSIS nine years ago, she says, there weren’t many women in high-level positions. And for a couple of decades after the inception of CSIS, most of the service’s women did not become intelligence officers, but rather were employed in other CSIS support functions. From the old vestiges of RCMP culture to a 50/50 executive cadre, how have women’s roles in Canada’s intelligence and security sector evolved?

***

As it did with other industries, World War II opened up careers for women in intelligence that hadn’t existed before. The main pipeline to these opportunities, as intelligence and national security expert Wesley Wark explained in an interview, was something called the British Security Coordination, led by Canadian William Stephenson, who is said to have been the real-life inspiration for James Bond. Based in Washington in 1940, Stephenson was unable to hire Americans — the United States was still a neutral player in the war — so he staffed many positions with Canadians, including Canadian women.

At the end of the war, many of the windows that had been open for women to work in the military industrial complex closed. “We don’t have a quantitative picture of how women fared in the Canadian intelligence system as a whole for many of the decades of the Cold War,” said Wark, who is a visiting professor at the Graduate School of Public and International Affairs at the University of Ottawa. “For the RCMP security service, for example — a very heavily male-dominated world — it was possible for women to gain some entry, particularly in the latter stages of the Cold War.”

But generally, opportunities for women were limited, and would have come about in a very particular way. “There was a kind of embedded old boys’ network within the Canadian intelligence community that was really responsible for recruitment and promotions,” Wark said. “So you had to find a way in — you had to have a supporter, a sponsor, a mentor.”

You can’t do business as usual; this isn’t about just trailing Russians around, this isn’t about even just trying to track down Islamist extremists.

As major global events forced the opening up of intelligence generally, barriers that had existed for women began to melt away. Louise Doyon experienced this first-hand, joining the service in 1990. Over the next 20 years, she occupied a number of roles, from analyst to intelligence officer to, eventually, two director-general positions.

Doyon started at CSIS during what she describes as a “where do we go from here” moment. During the Cold War, the service had predominantly focused on espionage, keeping its secrets close and only revealing a limited amount of information to a small number of actors.

With the collapse of the Soviet Union, threats to international security interests didn’t disappear — they morphed. The challenge for the Canadian intelligence community was to build up its analytical capability, in order to pinpoint what exactly these threats would look like. Doyon and a number of other women were brought in for this purpose, although, she says, “the analytic function was still not viewed as core, and there was still that ‘need to know’ [approach], so there was not that much sharing at the beginning.”

With the terrorist attacks in New York City on September 11, 2001, however, “the barriers broke.”

“Terrorism by definition means you have to be able to not only share information that you have gathered across communities internationally — the Five Eyes, non-Five Eyes [countries], the Europeans and others,” she said, referencing the decades-old intelligence group comprised of Canada, the United States, the United Kingdom, Australia and New Zealand. “You have to gain access to information that others have gathered, to put all those pieces together.”

This need to solicit cooperation and information from diverse communities around the world meant recruiting a more varied workforce, in terms of languages, cultural backgrounds and, of course, gender.

Becoming a Modern Security Service

Today, according to Stephanie Carvin, an assistant professor at the Norman Paterson School of International Affairs and an analyst with CSIS from 2012 to 2015, the organization is once again going through “tremendous change,” due in part to the fact that Canada is facing threats that are even more complex than those it faced after 9/11.

“You can’t do business as usual; this isn’t about just trailing Russians around, this isn’t about even just trying to track down Islamist extremists,” she said. “You’re now dealing with economic security issues — [Chinese technology company] Huawei, for example, which is not probably what was envisioned in 1984.”

Carvin believes strongly that security and intelligence services need to have social licence — the ongoing approval and confidence of the citizens they are serving — especially after the shattering of trust between the public and government that occurred in the wake of Edward Snowden’s surveillance revelations in 2013. She sees the creation of the new CSIS Women’s Network as a step toward the organization becoming a modern, accountable security service, which, given a lawsuit against it in 2017 for discrimination and harassment (now settled), is sorely needed.

Carvin describes her time with CSIS as positive and says she never felt she was discriminated against as a woman. She would, however, agree that on the operational side (versus the analytical) there’s a need for more leadership and mentorship.

“I do think it’s a good-news story — this doesn’t mean we shouldn’t be on the alert, or not critical or anything like that,” she said. “But this is the kind of way you do help to provide change.”

Doyon is also encouraged by the network and by the way the service has adapted since 9/11. “I’m not saying it was all easy, and there have been battles,” she said. “But now the number two of the service is a woman, and you have other women around the table at the executive level. You had three successive women as regional director-general in the Montreal region. That’s huge.”

At CSIS’s national headquarters, Doyon adds, “when you walk in, if you look at the people going in and out with their badges, you see a lot of women, a lot of young people, a lot of diversity.”

An Insider’s View

On a sweltering Friday afternoon in July, I visited CSIS headquarters on Ogilvie Road in the residential Gloucester neighbourhood of Ottawa. The building looks a bit like a triangular airport hangar, with rows of turquoise-tinted windows breaking up its grey façade. The stone walkway leading up to the front entrance is lined with flowers in bloom, in shades of purple and pink. Staff members — of various ages, genders and visible ethnicities — are milling around in the sunshine, clad in workout gear, shorts and summer dresses. It might be possible to forget I am visiting the home of Canada’s national intelligence agency, were it not for the concrete bollards and surveillance cameras.

Inside the building, the air is cool. I go through security and am led to a conference room off the main hall, where I am soon joined by Deputy Director of Operations Michelle Tessier — the first woman to hold the position — and Tricia Geddes, assistant director of policy and strategic partnerships.

The two women are candid in their commentary and have an easy camaraderie. Over the next 45 minutes, the conversation flows naturally as they recount what it’s like to occupy senior roles in an environment that historically has been dominated by men.

Now the service’s “number two” under director David Vigneault, Tessier was first hired in 1988 as a media analyst and became an intelligence officer in 1989. Looking back on her rise through CSIS, she says that while she has encountered resistance over the years, her response has always been to brush it off and let her performance speak for itself.

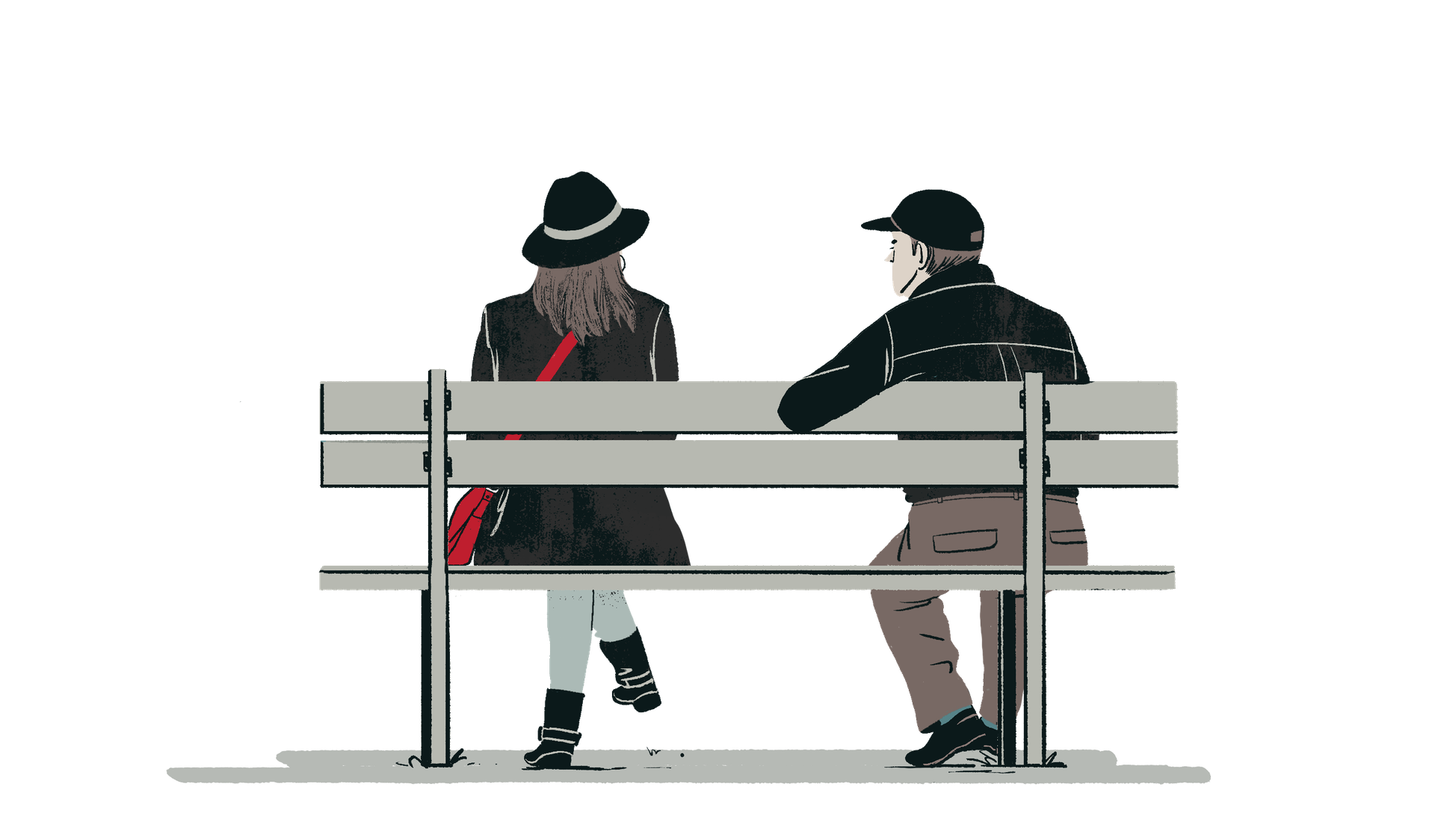

As an intelligence officer out in the field, her job was to recruit sources and persuade them to provide human intelligence to the organization. “Initially there were comments: ‘Oh, women can’t do that, nobody would want to talk to you,’” she says. “But I didn’t listen, and off I went to recruit my human sources.”

One highly specialized operational unit she joined had never had a woman in it before her. Her male colleagues had spent months trying to recruit a particular individual without success, using “more of an aggressive attitude — you know, ‘Give me the intelligence we need to know, we know you’ve got the information,’” she recalls.

“I literally sat there for a year and a half listening to [this individual talk] about his private life, and all the issues he was having in his marriage,” she says. Eventually, he told her he had decided to trust her, and started giving her intelligence.

We take up a lot of space at the table. There’s these women who are very powerful, not just in their position but in their personalities, taking up decisions. That’s pretty neat.

Tessier stresses that this — although she does believe women are great listeners — is simply an example: “I’m not saying a man couldn’t have done that; I’m sure there are men that have that patience, and I’m sure there are women who would say, Yeah, whatever, I don’t care about that.”

But she does think having that diversity in the officers available is important. “We work with a variety of communities, we knock on doors, we’re meeting people at airports,” she says. “A woman coming out of a particular country with a very harsh regime may not want to talk to a man from an intelligence service, because they think something horrible will happen to them. You send a woman in there, they just may feel more comfortable.”

When it came time for Tessier to move on from that particular unit, her colleagues asked for a woman to replace her, which, she says, was the greatest compliment she received in her entire career.

Unlike Tessier, Geddes started her career working on social policy for the Canadian government. She notes that while the cultural differences between that area and the national security community are “quite stark,” in the four years she has been with CSIS, the culture change in the building has been “remarkable.” She attributes this to the increase in the number of women in senior roles. “We take up a lot of space at the table,” she says. “How cool is that? Our young employees, the newcomers to our organization, see that there’s these women who are very powerful, not just in their position but in their personalities, taking up decisions. That’s pretty neat.”

She tries to be an example for junior staff by being open herself, authoring a blog about the challenges of being a working, single mother. It’s something that appears to be resonating with others; Geddes says that women often stop her in the elevator or hallways to tell her they appreciate her candour.

“I describe my complete failure in some of that kind of sense — that I will never get the cupcakes baked for the kids’ bake sale, yet I am an [assistant director] at CSIS,” she says. “Perhaps women are better at demonstrating vulnerability — that kind of speaks to the management piece too. When you can show that you are vulnerable as a human, it has a better outcome for your employees.”

That’s not to say that work is finished in terms of making a shift from the male-dominated culture of decades past. “There’s a lot of alpha-type people in this building, men and women,” Geddes said. “It’s what we recruit for…[but] I think now we need to make sure that we’re keeping space for people that don’t have those aggressive, assertive personalities, and yet [make up] a huge important piece of the puzzle.”

Tessier adds that it’s essential for staff to call out instances of unconscious bias, and for women in the organization to have full confidence applying for jobs or promotions that they might not feel fully qualified for: “I’m really, really confident, when I look at the women in this organization who are up-and-comers, that they will certainly carry on, but I would like us to get to the point where there’s a lot more comfort in women being more assertive with their own careers.”

Safeguarding Progress

Both Tessier and Geddes believe that the new Women’s Network can be instrumental in helping with this kind of progress, and both are themselves mentors for younger colleagues. “I love getting their questions, and they’re very curious — how did you do this, how’d you manage that,” Tessier says. “Just having the ability to reach out to somebody who has probably lived the same thing is worth its weight in gold.”

Former service members also see the value of the network, and say that despite the current encouraging breakdown of gender numbers, there are further improvements to be made. For example, according to documents released under an Access to Information request, the proportion of women among the employees resigning from the service rose from 45 percent in 2011 to 63 percent in 2016.

Facilitating upward mobility is still a challenge for the service. Carvin recommends that the Women’s Network try to assist with the designing of career paths for staff who are interested in staying at CSIS long-term. Although being an analyst was fulfilling, she recalls being concerned that her role had a “five-to-seven-year expiry date.” In a 2015 CSIS employee survey of all staff, only 48 percent said they believe the service does “a good job of supporting employee career development,” and only 50 percent were satisfied with their career progression (an issue, of course, for both men and women).

According to Wark, CSIS could also improve the support it offers to employees who are required to move to new locations. “One of the reasons why perhaps a network for women in the intelligence community came about relatively late is that, generally, it’s been a community where careers are based in one place,” he said. That is starting to change; CSIS has reportedly increased its international presence, and there may be more of a sense now that if someone wants to progress in the service, they will eventually have to take on some kind of foreign assignment.

Finally, here in Canada or abroad, as Tahera Mufti underlined, perhaps the most valuable benefit a network can provide is its simplest — an opportunity to connect CSIS employees with colleagues to whom they might speak more candidly than they could with family or friends. Working in intelligence can be a lonely business, and Wark thinks there is an increasing understanding of the mental health impacts that come with the job.

“There are stresses of this job that are crazy,” Carvin said. “There were times when I’d be working on a file and it was awful — like awful — and I would call my mom and say, Can you just tell me what you’re making for dinner? Because I just need to remember what normality feels like right now.”

“It’s tricky for men and women…there’s a reason why pay scales are a little bit better than certain areas, because the pressures are tremendous,” Doyon said. Still, she and many others would describe the service as a vocation, worth the complications that come with life as a spy. During 9/11, she says, “people didn’t count their hours — working 20 hours a day to make sure there were no threats here, or no targets here that were willing to go to the United States.”

And despite the significant shift from the macho culture of the 1980s, she considers the Women’s Network to be essential to safeguarding the progress that has been made over the last 35 years.

“As we are seeing in the US, and in certain quarters in Canada, rights, especially recent rights, are not considered God-given,” Doyon said. “They will be challenged on the basis of society, they will be challenged politically, and then it’ll have repercussions within organizations.”

Wark agrees that maintaining its social licence — its democratic legitimacy — should be a top priority for CSIS going forward, along with greater representation from Indigenous communities. “They can’t rest on their laurels and say, you know, we have a pretty good gender mix now, problem solved,” he said.

“They’re going to have to keep making sure that intelligence careers are seen as attractive widely to Canadians, and to young Canadian women, looking for careers in government.”