When it was announced in 2018, the national Cyber Security Assessment and Certification program for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) promised to elevate the cybersecurity posture of 98 percent of businesses in the country. Funded with $28.4 million, the certification program, dubbed CyberSecure, was formally launched in 2020 and aimed to get 5,000 SMEs certified by 2025. But in its first three years, only 41 companies have obtained certification. The trend is downwards. As of August, only two companies have become certified in 2023.

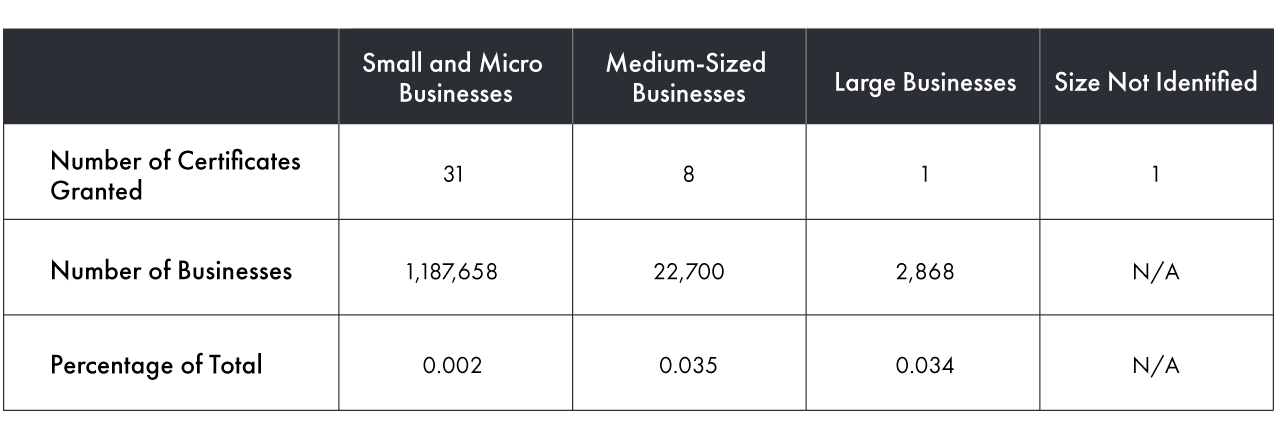

Table 1 shows the total number of certificates granted during the life of the program through August 2023, according to data I obtained about the program through a recent access to information (ATI) request, compared to the number of businesses of these sizes in Canada in 2022. This includes all certifications granted through the program, including several that have since expired without being renewed after the two-year period.

Table 1: Canadian Businesses Achieving CyberSecure Certification at Least Once as of August 2023

To put things in perspective, the costs of the program are disproportionate to the results so far, given the certification is estimated to cost only $2,000 to $5,000 to obtain. Also, the certification was never intended to apply to large businesses; however, one such company — the private executive health-care clinic MedCan — has obtained it. The program was originally developed in collaboration with Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada (ISED), the Standards Council of Canada (SCC) and the Communications Security Establishment. ISED touted the program in the following way: “Transitioning to a digital economy brings many opportunities, but also new challenges for Canadian individuals and businesses, including cyber threats. ISED continues to support Canada’s National Cyber Security Strategy to help SMEs protect themselves from cyber threats. This includes implementing, overseeing and evaluating the cyber certification program CyberSecure Canada.”

When it was announced in 2018, the national Cyber Security Assessment and Certification program for SMEs promised to elevate the cybersecurity posture of 98 percent of businesses in the country.

But the program has not helped very many actors. A pilot project launched in 2021, which aimed to get 175 SMEs CyberSecure-certified, failed to achieve its modest objective. Despite this lack of success, the SCC still clings to the phantom objective of certifying 5,000 SMEs by 2025 — a number that is a key assumption baked into its operating budget as an anticipated source of revenue. The inevitable budget shortfall is bound to require further federal funding for the SCC.

Some might also fairly criticize the program as a veiled handout, as displayed by the type of grants given to certifying bodies — such as the cybersecurity entity in Quebec that received an $820,125 grant expressly to “enable the organization to provide mentoring to 150 businesses to obtain the ‘Cybersecure Canada’ certification, an [ISED] program.” (It is not clear if the entity receiving the grant mentored any businesses to obtain CyberSecure, since ISED refused to disclose under my ATI request any information regarding which certifying bodies have actually granted certifications.)

Despite the certificate program flopping, it seems we are about to do it all over again. In May 2023, then Defence Minister Anita Anand announced that Canada would set up a cybersecurity certification for defence contractors. The program is being funded with $25 million. One worries about the creation of a program resembling CyberSecure again — or perhaps resembling Cyber Essentials in the United Kingdom, a required certification for doing business with government, which is widely criticized as inefficacious.

To be fair, these programs have good intentions. As the Royal Canadian Mounted Police notes, cybercrime in Canada continues to reach historic levels. In the face of such threats, certification programs such as CyberSecure seem like well-intentioned attempts to turn the tide. But as a voluntary program, CyberSecure always had an incentive challenge. Although ISED presents many good reasons why companies should get certified, the federal government still has not done enough to clarify why parties actually need it.

Other projects, incentives and compliance requirements could help. For example, in February 2023, the Centre for International Governance Innovation proposed to the Standing Committee on National Defence in the House of Commons, “implementing a tax credit system as an incentive to help increase the overall level of cybersecurity in the country and reduce the risk of cyber-attacks on businesses.”

There are lots of other ways we can get actors to bolster their cybersecurity posture, too. In the United States during Barack Obama’s administration, Special Assistant to the President and Cybersecurity Coordinator Michael Daniel laid out a handy list of ideas such as cybersecurity insurance trade-offs, preferential procurement, liability limitation of breach disclosures, public recognition (as the Dutch government cleverly does) and targeted research.

Beyond SMEs, an area of real and pressing concern is critical infrastructure. Any survey of recent events shows why Canada needs to move much faster in this area. In 2021, the ProxyLogon attack by HAFNIUM comprising multiple zero-day exploits targeting Microsoft Exchange servers was discovered to be enabling “long-term access to victim environments” through the use of web shells that obtained email and account credentials. The Federal Bureau of Investigation even obtained an order proactively to enter victim computers and delete the shells.

More recently, in May 2023, the Chinese state-sponsored Volt Typhoon group was caught targeting critical infrastructure in the United States with malware. In July, the Storm-0558 attack breached the State Department, directly targeting diplomats and officials dealing with the China portfolio just prior to Secretary of State Antony Blinken’s visit to China. In August, the Canadian Centre for Cyber Security released a warning that Canada’s critical infrastructure is likely being targeted by malicious actors, too.

Beyond SMEs, an area of real and pressing concern is critical infrastructure. Any survey of recent events shows why Canada needs to move much faster in this area.

In June 2022, the federal government introduced Bill C-26, which included the Critical Cyber Systems Protection Act that establishes various legal requirements for critical cyber systems. The bill promises to address many shortcomings in Canadian legislation. But as I and Russ Walton point out in a recent article, the bill entrenches a patchwork approach, lacks sufficient oversight and transparency, and contains diluted obligations with weak compliance measures.

The worst aspect of Bill C-26 is that it follows a registration-based system of regulation. It only applies to entities the federal government itself deems “critical.” This approach will do little to elevate the cybersecurity posture of other private actors that the government neglects to identify proactively. This approach mirrors a European regulation introduced back in 2016, which has now been replaced by a size-cap system that automatically applies to entities with certain attributes.

Canadian law makers should hurry now to learn Europe’s lessons and amend its law accordingly. There are also important lessons to be learned from Australia, which was an early mover in passing a law requiring certain operators of critical infrastructure to meet assistance, reporting and direction obligations.

Canada’s cyber incident reporting landscape is flawed for other legal reasons, too. Although Bill C-26 arguably covers ransomware incidents, it does not contain any elevated or explicit requirements for reporting ransomware attacks and payments, unlike the American Cyber Incident Reporting for Critical Infrastructure Act, which came into force last year. It is striking that Canada’s Bill C-26 neglects ransomware when the Canadian Centre for Cybersecurity notes “ransomware is almost certainly the most disruptive form of cybercrime facing Canada.”

The overall narrative in this area is one of stalling. Bill C-26 was introduced almost a year and a half ago, and within months was being criticized for languishing. Canada is now one of the last countries in the Five Eyes intelligence alliance to be moving on legislation concerning critical infrastructure cybersecurity. Combined with a sputtering cybersecurity certification program, the country’s recent track record leaves much to be desired.