Over the past three years, Canada’s attempts to regulate large online companies have been something of a bloodsport. In May 2021, a cross-section of Canadian internet activists and scholars accused the federal government of flirting with authoritarianism. The response by many critics to specific legislation — Bill C-11, the Online Streaming Act, and Bill C-18, the Online News Act — was no less heated: cries of “Liberal censorship” and that the government had empowered itself “to control what Canadians can see and say online,” thereby enabling its bureaucrats to act like Nazis and Soviet apparatchiks and ushering in an era of “digital totalitarianism.” All this, about laws that do little more than bring online companies into a decades-old Canadian cultural policy regime and require large online platforms to negotiate payments to the news media companies.

Given this recent history, the Liberal government is surely ecstatic about the relatively muted response to

Bill C-63, its long-awaited, much-delayed legislation to regulate harms caused by social media companies. Since the Online Harms Act was introduced in February, most criticism has focused not on its ostensible subject but on several unrelated, unexpected amendments that would, among other things, expand the number of offences that can be brought under the rubric of hate crime. Intentional or otherwise, these amendments have acted like a legislative lightning rod for the rest of the bill.

But there’s another reason why the actual social media regulation part of Bill C-63 hasn’t gotten critics’ blood boiling. Outside of a couple of important but narrow issues, the Online Harms Act really doesn’t do that much. There hasn’t been much opposition because there’s not much here to oppose. Take out those troublesome amendments and this is a bill designed to pass easily by offering the smallest possible political target.

But this comity comes at a steep price.

Overly Narrow Scope

To start, the bill’s list of in-scope harms is far more limited than it could be, both politically and substantively. It defines as “harms” only seven specific heinous activities, most of which are already clearly illegal: intimate content communicated without consent; content that sexually victimizes a child or revictimizes a survivor; content that induces a child to harm themselves; content used to bully a child; content that foments hatred; content that incites violence; and content that incites violent extremism or terrorism.

The bill’s teeth are reserved for only two categories: intimate content communicated without consent (so-called revenge porn) and content that sexually victimizes a child or revictimizes a survivor. These are the only cases where the proposed regulator is to be given the power to compel a social media company to take content down (within 24 hours).

The rest of the bill proposes a slightly modified version of the self-regulation status quo. People can complain to the regulator about what they see or read — such as material affecting children, or hate speech — but the company would still be allowed to decide whether such content should be taken down. Companies would only be required to have clear and transparent complaint processes, and, in the case of children, measures to protect them from bullying and self-harm. (Terrorism and child sexual abuse material are also part of the bill. Again, this is content that even an ardent civil libertarian would have trouble defending.)

This focus on harms to children implicitly leaves adults out of scope on the central issue of online bullying and harassment. Which is a problem, because online harassment isn’t something that stops when you graduate high school. And it’s not something that many adults can just deal with on their own. Adults — in particular, women, racialized and queer individuals, and other marginalized individuals and groups — have been at the forefront in calling out the often devastating consequences of online harassment, much of which doesn’t rise to the legal level of hate speech but is nonetheless socially and individually harmful. Yet the legislation doesn’t go there.

Consider the extensive list of harms related to technology-facilitated gender-based violence enumerated by the Women’s Legal Education & Action Fund (LEAF). Would abuse such as online mobbing or swarming and trolling be covered by this legislation? Are those hate speech? It doesn’t appear so. In any case, the legislation only requires that the company have a plan to deal with complaints following a self-determined transparent process.

On its face, this bill embraces a “positive freedoms” approach to speech that emphasizes the need for equality, in order to secure free-expression rights for all. Such an approach correctly recognizes that the absence of rules itself chills the speech of marginalized individuals and groups and reinforces the position of the powerful.

So, it’s disappointing that the bill appears primarily concerned with going too far in protecting marginalized Canadians. The bill explicitly states that it “does not require the operator to implement measures that unreasonably or disproportionately limit users’ expression on the regulated service” but doesn’t include a direction of equal strength related to promoting equality.

The result is legislation that doubles down on exactly the speech-chilling approach that creates the need for a law like this in the first place.

The legislation does reintroduce the ability of Canadians to file complaints about online hate speech with the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal (although University of Windsor law professor Richard Moon comments that this process would likely either overwhelm the tribunal or be so selectively used as to render the process moot). But compared with measures taken in other jurisdictions, it’s thin gruel.

Australia’s Online Safety Act, for example, does not restrict its protections to children, and it can direct a service to remove content that meets a legal threshold. What’s more, it covers more than social media platforms, including search engines and electronic messaging services (the latter of which can reach as many people as a social media network).

Daycares or Cigarette Companies?

Overall, the bill takes a light touch to regulation: much of it is focused on improving researchers’ access to data, and the transparency and accessibility of social media companies’ flagging and complaints mechanisms. Companies are also required to provide digital safety plans outlining how they’re meeting their obligations under the legislation.

The legislation’s spirit is captured by its motivating concept, the “duty to act responsibly”: that companies need to consider how their product will affect their users. The regulator can dictate changes but, for the most part, it’s up to the company to decide what to do.

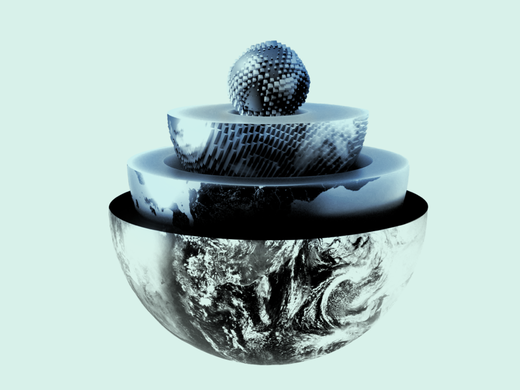

And here we come to the fundamental flaw with Bill C-63: it treats social media companies like daycare providers, when they’re actually more akin to cigarette makers.

A light-touch duty to act responsibly makes sense for for-profit daycares. They deliver a socially desirable product but may face pressures to cut corners and compromise their product. The regulator’s challenge is therefore to ensure that these companies deliver the child care they have agreed to provide, with acceptable quality and safety. They need to create guardrails to keep everyone in bounds. Here, self-regulation and concepts such as duty of care, supplemented with some punitive measures, can make a lot of sense.

Now, consider tobacco companies. If anyone argued they could be regulated by a duty to act responsibly toward their customers, they’d be laughed out of town, yes? Because the problem with tobacco is the product itself, which eventually kills people, if used as intended.

There’s a direct conflict between the public interest in limiting the sale and consumption of tobacco for health reasons and these companies’ economic interest in selling as many cigarettes as possible, despite the health risks. They thus have had enormous incentives to resist and dodge any restraint on their core business, including by burying critical in-house research (sound familiar?).

In such a sector, light regulation, or self-regulation, will yield only cosmetic changes.

Regulating the Business Model

The harms from social media companies — violent hate speech to the point of helping to foment genocide, harassment and discrimination, encouraging children to self-harm — are not aberrations. These harms are inherent to their data-harvesting, surveillance-based, for-profit advertising business models. (This argument ignores those social media networks designed to circulate socially harmful content, for whom a duty to act responsibly is even less tenuous as a regulatory strategy.)

Indeed, companies have tended to be cavalier about online harms, however these are defined, because the social-media platforms that are the ostensible focus of regulation are often not their actual business. As Shoshana Zuboff correctly argues in her book, The Age of Surveillance Capitalism, these platforms are merely façades for the business of harvesting data, which the companies can use for advertising or, in effect, sell.

In a data-driven economy, the goal is to collect all the data, all the time. With social media, this is done by working to capture and monetize attention, no matter how socially objectionable or damaging the content. And as every newspaper publisher knows, conflict, scandal and mayhem drive sales.

When it comes to regulation, restrictions on companies’ ability to maximize data harvesting, even when done to limit social harms, are deemed an existential threat to the bottom line. These companies are thus incentivized to work around regulations designed to make their networks healthier for users.

In fact, social media itself isn’t the problem; the present business model is. If these companies made their money differently, through display ads, or subscription fees, or government subsidies, they would place greater emphasis on running user-friendly social networks. They would be more like daycares, because they’d be in the business of providing social media services. Unfortunately, in the world as it currently exists, the actual content on these platforms is secondary to the data they gather and monetize.

A duty to act responsibly will only work when the product itself isn’t causing harm. When the product itself is the problem, you have to directly regulate these companies’ actual business — in this case by restricting their ability to collect and monetize all the data, all the time.

Of course, this is easier said than done. Policy makers and academics rarely discuss the possibility of indirectly addressing these issues via economic policy — such as through taxing data collection and personalized advertising, banning personalized advertising, or requiring that people pay directly for social media services. And while an economic approach would sidestep thorny speech issues, there’s no doubt these companies would make this a battle for the ages.

The difficulty of the fight, however, doesn’t obviate its necessity. Exploring economic regulation would represent a much-needed policy advance in this area.

In fairness, the ability to compel action to deal with (again, a limited set) of harms raises the possibility that the regulator could end up somewhat regulating the business model. Maybe. We can’t be certain because, as University of Ottawa law professor Michael Geist has pointed out, so much in Bill C-63 is left up for the regulator to decide.

We’ll only know the actual meaning of this duty to act responsibly (as it relates to a very narrow list of harms and so long as it doesn’t unduly restrict free expression) once the regulator sets its threshold for intervening in a company’s internal affairs and the measures it is prepared to order and enforce. And all this is conditional on the regulator’s ability to compel notoriously pigheaded companies (which have absorbed billion-dollar fines without blinking) to obey. To state it mildly, the stage is not set for success.

The Best We Can Do?

Despite these criticisms, there are good things in this legislation. While the focus on sexual victimization content is far too limited, it is nonetheless an important move that will help real people.

And the proposed regime does hold glimmers of potential. Most notable is the necessary creation of a regulator and ombudsperson who will have significant leeway to investigate and act, including to compel a company to adopt certain measures in pursuit of the legislation’s (limited) objectives. The legislation also seems to leave the door open for the regulator to expand its mandate to focus on (undefined) “safety” issues beyond the specific harms delineated in the bill.

Furthermore, the fixes I’ve suggested throughout — rebalancing the legislation toward equality rights, bringing adults, and not just children, under measures regarding online bullying and harassment; and an Australian-style expansion of the legislation’s scope — should, and can, be addressed in committee hearings.

Overall, this legislation creates a regulator with the potential to do good, if it is well-funded and staffed by suitably ambitious people. But it is a series of half measures. What’s most needed is for the government to fully embrace equality and freedom from domination as prerequisites for true freedom of expression.

When one considers the severity of the challenge and the years spent on this issue, it’s hard not to be critical. Bottom line: This politically expedient, unambitious legislation fails to address the very real needs of so many Canadians. Some things should be worth fighting over.