In July, the Canadian Centre for Cyber Security (the Cyber Centre) released a new addition to its “Awareness series” providing guidance on information technology security for organizations and individuals: “Generative artificial intelligence (AI) — ITSAP.00.041.” In it, the Cyber Centre outlines how generative AI is being used, explains some of the risks this technology poses, and recommends strategies for addressing them.

While the document is an important and welcome first step, it would benefit from further elaboration and greater detail. Countless Canadians will use these new AI tools. When they do, the data they input as they interact will be delivered to — and stored by — these tools.

Should Canadians use the new AI tools without effective safeguards, we will be allowing precious data assets to leave our borders, to the benefit of the companies that operate AI models. Notably, each of the three major chatbots (ChatGPT from OpenAI, Google Bard and Microsoft 365 Copilot) are owned and controlled by American tech firms.

Our current technological moment is the culmination of three radical recent transformations.

First, most of the world’s computing and data resources have moved into networks and “the cloud.” Second, many government and private sector workers — in Canada, certainly — have transitioned to remote work carried out using these computing resources. Finally, cloud-based generative AI systems such as ChatGPT and Bard have emerged in the cloud and achieved competence in many of the tasks that office workers tackle every day.

Cybersecurity Is Changing

The rapid shifts of the past decade, and in particular the explosive changes of the past year, have created uniquely high risk for the information systems we rely on in business and government for the functioning of society.

Make no mistake — the cybersecurity strategies of even the recent past are no longer adequate. Bad actors won’t waste time attacking yesterday’s technologies using yesterday’s methods — and Canada’s government and businesses must not content themselves with their (still limited) adoption of solutions for yesterday’s problems.

Cloud and distributed computing, remote or mobile work, and the emergence of generative AI, taken together, are what make this a moment of profound risk. Workers in both government and the private sector now rely every day on dozens of cloud apps, each ripe for account theft, each with its own vulnerabilities. Data is distributed in such a way as to make it impossible to protect it with old “cybersecurity perimeter” strategies, and many of the nuggets of data we work with on our devices are near a “share” button that makes it troublingly easy for data, including the most confidential and sensitive data, to wander around the world without due care.

The Cyber Centre’s guidance document calls for strong authentication mechanisms, such as multi-factor authentication (MFA), as foundational protection against data loss risks, and I agree with this recommendation. All government and private organizations that have not already done so should immediately adopt single sign-on tools, which reduce the number of logins users must manage, along with MFA technology that provides basic protection against account theft.

However, government agencies and businesses must also deploy cloud access security broker (CASB) and data loss prevention (DLP) tools to regulate the flow of cloud data even for legitimate users. These tools are powerful ways to ensure that data controls and policies are actually adhered to — not just concepts outlined in training.

Unfortunately, many Canadian agencies and companies are mired in half-completed cloud transitions without any formal cloud security at all. The Cyber Centre’s recommendations fail to address this point.

Users are asking AI apps to read and write letters, summarize human resources files, evaluate medical case histories, write legal briefs, and more. Yet an AI bot shouldn’t be trusted with such information.

Any member of the new army of remote workers might log in this morning only to have their device stolen by lunchtime — from their car or the corner coffee shop — and realize their data is now accessible to a thief because they are still logged in. And many will work all day connected via a public hotspot where, even with their device still in hand, their sessions can be intercepted. Logins — even when protected by MFA — are no longer any guarantee that a remote user is who they claim to be.

When it comes to this category of risk, the Cyber Centre’s recommendations don’t go nearly far enough. Tools to ensure that a worker is authentic — in particular, continuous authentication methods — not only exist, but have been with us for nearly a decade. For example, at Plurilock, the Canadian company I head as CEO, we offer behavioural biometric technology that validates a user’s identity through their hand movements on the keyboard or mouse.

Such tools operate all day to ensure that a worker is authentic, and end access — to cloud apps, to files, to AI chatbot sessions — if a new person is detected. Yet very few government agencies or companies have adopted continuous authentication as a cybersecurity measure. There is no excuse for this.

Continuous authentication mitigates many of the risks that the Cyber Centre’s guidance discusses, including phishing attacks, social engineering attacks and business email compromise. It ensures that even if a stranger — whether another human or an AI agent — is able to gain illicit access to a system, that intruder will quickly lose access before it can be exploited.

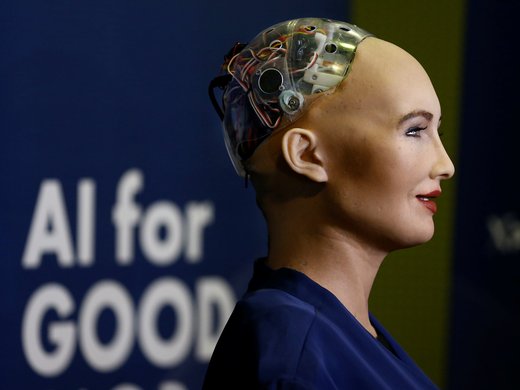

The focus of the Cyber Centre’s new set of recommendations is generative AI itself, and justifiably so. With the sudden, explosive adoption of tools such as ChatGPT and Bard, all the systems that government and private sector employees use must now be treated more like potentially malicious people than like software.

Users are asking AI apps to read and write letters, summarize human resources files, evaluate medical case histories, write legal briefs, and more. Yet an AI bot shouldn’t be trusted with such information. There are no guarantees that a tool won’t “share” secrets later on — whether because it “learned” these secrets, then recalled them for someone else, or because secrets remain stored in a stolen AI account’s history, for a thief to eventually retrieve.

We must also realize that the risk isn’t limited to ChatGPT or Bard directly. The AI groundswell has led app makers of all kinds to rapidly embed generative AI technology into their own software. Employers, government agencies in particular, must understand that for whatever purposes employees might be using AI — be it proofreading assistance, providing creative suggestions or highlighting mistakes — AI is now ingesting their work regularly, in many different applications.

Unfortunately, beyond a call for governance (policies) surrounding AI use, the Cyber Centre’s publication has limited practical advice to offer to government agencies or businesses with employees rapidly taking up ChatGPT and Bard, whether their use is officially sanctioned or not.

The Centre’s recommendations to train data sets carefully and choose only tools from security-focused vendors are, in practice, simply another way to say “Don’t let your employees use ChatGPT or Bard.”

But this is not practical advice. It’s clear that employees in government and business will use ChatGPT and Bard. It’s not a question of if, but of how.

To Lead and Win in the Age of AI

We need to develop the AI equivalent of firewalls for networks or MFA for logins — cybersecurity tools that support and ensure governance — rather than simply beg government and private sector workers to comply voluntarily.

It is up to Canadian technology firms to work fast to develop a new generation of powerful, practical security solutions for AI — solutions that enable government agencies and businesses to turn AI governance policies into real guardrails that don’t rely on user competence or goodwill. At present, there simply aren’t enough AI and data safety tools for agencies and companies to “adopt.”

Policy makers, for their part, must move now to better support the development of AI safety, and they must do it at a speed that keeps pace with AI’s rollout. Leadership and funding for new technology must arrive quickly; government must partner with industry to develop tools to make AI use safer. Those tools must then be immediately deployed.

Canada is one of a handful of countries well-positioned to lead the world into a cybersecure future. That the Cyber Centre has provided new recommendations around AI and cybersecurity shows that Canada’s government understands this. But I am not convinced that our policy makers or regulators recognize the gravity of the situation, or how urgently we need these already overdue technology solutions for AI safety.

Canada’s AI story can be one of productivity and innovation or a nightmare of unprecedented data leakage, privacy loss and cybersecurity failure. Which will it be? We had better decide quickly.