Elections are a flashpoint for understanding the health of a democracy. They focus minds on questions around democratic legitimacy and functionality. What is the turnout and what does it reveal about democratic engagement? How are campaigns financed? Is quality information available to citizens making their decisions? Do all groups have fair access to the democratic process? And, crucially, how have social media and online platforms affected elections over the last decade?

The Brexit referendum and the election of Donald J. Trump as US president in 2016 catalyzed debates about the influence of social media. But such discussions are often too narrowly focused on Europe and North America. Likewise, social media companies have concentrated their oversight and control systems on English-language and North American content.

To understand the role of social media in elections more broadly, therefore, we need to move beyond analyses that focus on the two continents where platforms spend the majority of their content moderation budgets.

On October 18, the Centre for the Study of Democratic Institutions and the Konwakai Chair in Japanese Research at the University of British Columbia organized a panel of experts from three continents to assess electoral disruption caused by social media in different contexts. The event aimed to extract general patterns and identify factors that explained different types of disruptions. Speakers explored the cases of the 2022 elections in South Korea (Ju Oak Kim, professor, Texas A&M International University), Kenya (Angela Oduor Lungati, executive director, Ushahidi), the Philippines (Aim Sinpeng, researcher, University of Sydney), and Brazil (Ivar Hartmann, professor, Insper [São Paulo]). These contests represent a good sample of recent elections in middle-income countries with varied demographics, with respect to geographic and ethnic backgrounds.

Among the panellists’ findings, four stand out.

First, and most obviously, each country’s digital political marketplace involves multiple online platforms. All have experienced increasing economic incentives to participate in, and promote, misinformation and disinformation.

In the Philippines and Kenya, a misinformation industry (with private firms running information campaigns for profit) has emerged. In Kenya, Facebook, Twitter and TikTok are all crucial. Private firms such as Cambridge Analytica and Harris Media, LLC have also been involved in targeted campaigns. Facebook and Twitter seem to have been more responsive than TikTok in addressing electoral misinformation, for example, by switching off the trending section or stopping group recommendations.

In the Philippines, Facebook, WhatsApp and YouTube are the major players. Grassroots influencers are the new disruptive force. At the same time, television continues to be very important and influential as a communications medium around elections.

In Brazil, by contrast, private messaging platforms are most influential: WhatsApp is the key political platform, although Telegram is another important player. Data protections make disruptions harder to recognize and monitor. Brazil also saw a much more centralized and orchestrated campaign of disinformation from the top during its recent presidential election.

South Korea mixes national and global platforms. Here, social media platforms have enabled politicians to circumvent older electoral rules. Twitter and Facebook are important, and YouTube is a rising force. The Public Official Election Act regulates advertisements in press and broadcast media during elections, but does not regulate campaign ads on social media. The Korea-based KakaoTalk app also plays a huge role: over 90 percent of all South Koreans use the messaging service.

Second, all speakers emphasized the impact of social media, particularly in changing politicians’ behaviour.

In the Philippines, micro-influencers have emerged as an important new element, although they are very hard to track and monitor because they are not centrally coordinated.

In South Korea, politicians and political parties have seized social media as a tool to initiate and spread political disinformation. However, the KakaoTalk platform responded by creating an elections tab with relevant information, and a mechanism to report false information.

In the Philippines, the population is extremely active on social media, particularly Facebook. Micro-influencers have emerged as an important new element, although they are very hard to track and monitor because they are not centrally coordinated. Platforms have responded with targeted removals of misinformation: Meta took down six million accounts in the Philippines from Instagram and Facebook.

In Kenya, powerful disinformation campaigns specifically target candidates, sometimes using local languages that are not effectively monitored by global platforms. Similarly, in the Philippines, Facebook algorithms pick up hate speech in Tagalog, but not in Bisaya. People switch languages and dialects to achieve their aims. To combat this, Facebook and others must adjust to language diversity, as Berhan Taye and many others have been pointing out for years.

In several countries, the very notion of the legitimacy of elections became a core battle in the midst of duelling narratives, a process that also revealed the global reverberations of Trump’s denying the results of the US electoral process. In Brazil, Jair Bolsonaro’s camp has fostered broad mistrust in the electronic voting system, with the aim of discrediting electoral outcomes. Remarkably, as Ivar Hartmann points out, the broad effort at disinformation in Brazil has had a more contained effect than similar efforts in the United States, due to a very powerful centralized electoral commission and Supreme Court.

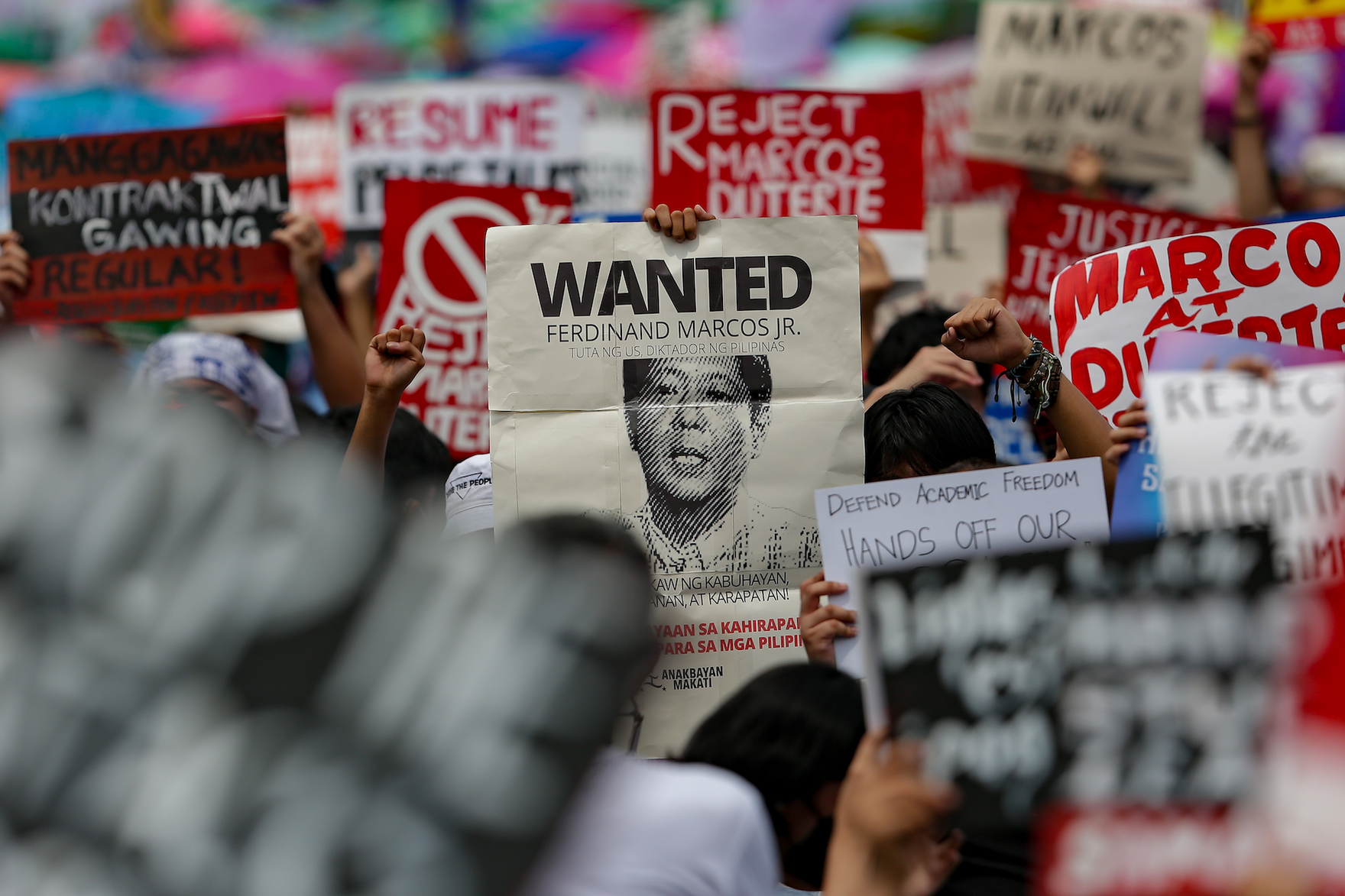

Third, the panellists talked about the varying effects of these social media campaigns, which can range from a sweeping reinvention of political realities to a reinforcement of existing beliefs and an increase in the turnout of some voter groups. In the Philippines, a major development has been the “rewriting” of Ferdinand Marcos Sr.’s legacy prior to the recent election. In Brazil, the Bolsonaro camp sought to rewrite history using digital platforms, reframing the nature of government rule under the military dictatorship. Platforms are less effective at addressing such broad narratives than they are in taking down accounts or checking specific facts.

South Korea experienced a wholly different dynamic: that of fan culture around Korean pop music (K-pop) merged with political campaigns. Fans idolized politicians as though they were K-pop groups, for example, by dramatizing their personal stories. Meanwhile, in Brazil, religious undertones dominated, as political leaders were portrayed in messianic ways.

In Kenya, platforms partnered with local fact-checking organizations to label false information. However, outcomes were mixed. It is not clear that local organizations have the capacity to deal with the torrent of problematic information on platforms, particularly in local languages.

Finally, presenters discussed the wide range of local responses to social media disruptions. Social media platforms have played a more active role in addressing disruptions than in previous elections, including better recognition of their role in elections, and, in some cases, early attempts to address the harms created.

New local actors and innovations offer a particularly important new trend toward improving monitoring and responding to misinformation. In Kenya, global not-for-profit tech company Ushahidi offers an important example of civil society partnering with platforms to develop mechanisms tailored to local contexts. National media platforms, such as KakaoTalk in Korea, are also more responsive to local demands for better monitoring. Yet much remains to be done, and local organizations often lack sufficient support.

Overall, as emphasized by presenter Aim Sinpeng (who has also recently written about the high levels of online abuse experienced by female politicians active on social media in Southeast Asia), social media and platforms can play a profound role in electoral disruption, but the ways this disruption plays out can vary significantly, and are both time- and context-specific. The four cases explored by the experts during this event demonstrated a great range of outcomes and highlighted the pitfalls of broad generalization. We need to move away from sweeping assessments toward more nuanced comparisons.

As Nic Cheeseman and Brian Klaas have argued in their book How to Rig an Election, authoritarian leaders find ways to hold elections and rig them long before voters enter polling booths, which points to the “limitations of national elections as a means of promoting democratization.” Nonetheless, electoral democracy is worth fighting for, worldwide. Beyond the many offline threats to fair and democratic elections that exist, digitally conducted campaigns present new opportunities for disruption and disinformation.

Studying the role of social media in elections in Brazil, the Philippines, South Korea and Kenya offers important lessons — among them, that policy makers should develop tailored solutions for these problems based on individual states’ contexts, rather than assuming one size fits all.