Throughout history, technology has played a pivotal role in shaping human development, driving transformational successes such as the Agricultural Revolution and notable failures such as the development and repeated use of chemical weapons. In 2024, the diffusion of emerging technologies will continue to accelerate across the planet, and we have only a brief window of time to get ahead of the curve.

Public, private and non-profit sector leaders need to act quickly and decisively at both national and international levels to frame and guide policy and regulatory directions. Collective action — or inaction — will have critical impacts on future generations if we do not carefully align the current wave of technologies with human values and interests.

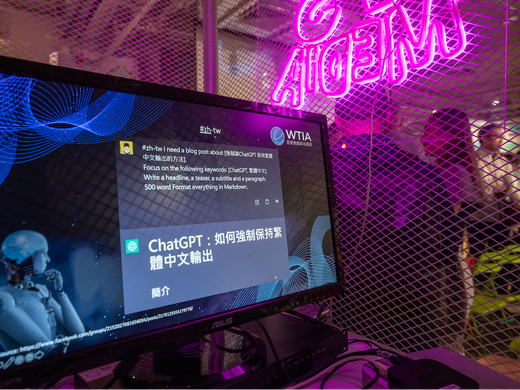

The rapid rise of generative artificial intelligence (AI) and other new technologies is clearly a double-edged sword. The potential benefits through advancements in science, economic productivity, health care, social services, environmental protection and other sectors are compelling. On the other hand, the risks and challenges are enormous: disinformation undermining democracy and the social fabric of society, the use of fully autonomous weapons, the infiltration of AI-driven cyberattacks, and the exacerbation of inequalities within and between countries, to name but a few.

AI is already deeply embedded in various sectors, and generative AI — systems capable of producing new content and data — along with other key technologies are poised to reshape our world over the coming years, evolving in a highly volatile and interdependent global context. With the concentration of control and benefits in a limited number of large corporations in a few countries, there are concerns about market dynamics and undervaluing key issues such as individual privacy and freedom, as well as global access for all countries.

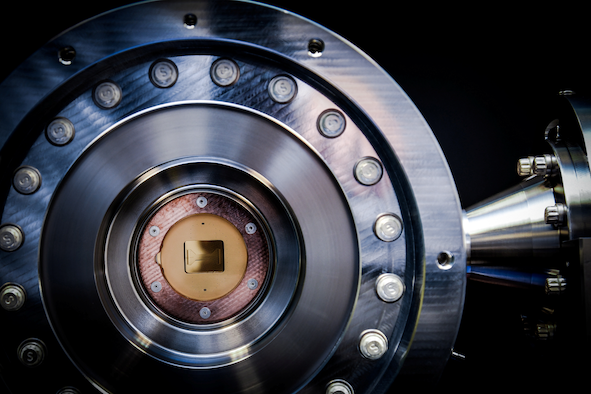

Quantum computing, with its potential to perform complex calculations at unprecedented speeds, could significantly disrupt fields such as cryptography, introducing novel security challenges to safeguarding secure information systems such as banking.

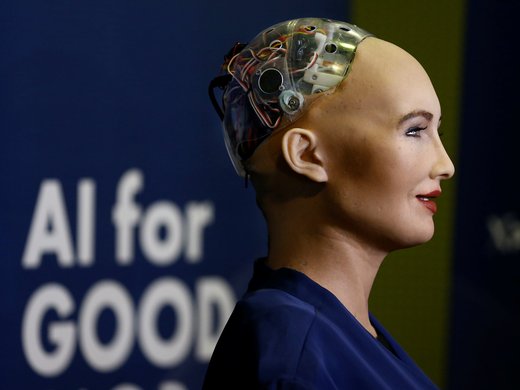

Neurotechnology, which can facilitate direct human brain/computer interfaces, shows great potential in treating specific neurological conditions but also introduces significant ethical concerns, particularly related to human testing and the implications for individual rights.

The Internet of Things and autonomous technologies are transforming business models from manufacturing to transportation, often with dual-use dimensions. Web3 and decentralized protocols promise more control over personal data and more interoperable social networking, but they also present new regulatory challenges for financial applications and can have significant environmental impacts due to their energy-intensive nature.

Digital public infrastructure can offer promising governance models for countries to create a foundational framework for broad public benefit in the digital age, but it also creates risks for overly centralized control and surveillance, especially if managed by governments alone. Biocomputing and synthetic biology, still in nascent stages of development, have the potential to revolutionize sectors such as health care and energy through innovative applications such as smart therapeutics and biofuel production.

Hyper-rapid technological change and global competition will only accelerate. It should be no surprise that, in a policy vacuum, companies will develop and deploy new technologies apace without fully considering the broader implications. In addition, technologies emerging today will be strongly shaped by the global forces of macroeconomics, geopolitics, climate change and new governance models. As things stand, there is currently far too little public debate at the national level — and only superficial discussions globally — about how new technologies will be managed so that they align with societal values and interests and so that governance systems balance risk and reward.

Responsible innovation can advance through both existing governance fora, such as the G7 and G20, as well as through new intergovernmental and multi-stakeholder initiatives. In 2009, following the global financial crisis, G20 countries coordinated their economic stimulus to avoid a full-blown global depression. Existing fora can help manage market externalities inherent in new technologies and ensure protection of human values and interests. They should give priority to support development of a clear set of criteria for responsible investments to help guide public and private sector investors, and to establish standards to embed responsible innovation in the work being done by companies.

However, new platforms are also needed to bridge different groups to create and disseminate best practices, as a key part of building a coherent international system. The legitimacy of these changes must be premised on social licence. States should urgently engage stakeholders and the public in understanding and debating the positive and negative impacts of technological innovation. Responsible technological advancement is not a given. A choice must be made to favour it, similar to choices made to protect the environment over recent decades. Responsible innovation for technology needs to be a core policy priority, and action in 2024 can be pivotal.

This piece first appeared in Tech Policy Press.