On September 18, the US administration announced that it would ban new downloads of the TikTok and WeChat apps. Then, on September 19, the plan was halted when President Donald Trump gave tentative approval to a deal that involved the creation of a new, US-headquartered entity called TikTok Global. As part of the new deal, Oracle and Walmart would own a combined 20 percent of the newly created entity; the remaining 80 percent would be owned by ByteDance, TikTok’s parent company.

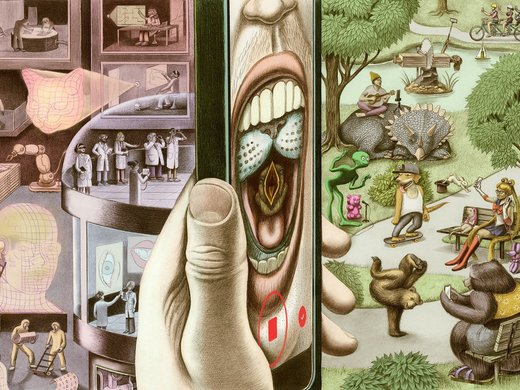

While decisions related to both apps have been postponed, the proposed ban — and the deal that followed — raises a number of questions about government power over foreign technology firms, about cross-border data flows and about the state of a global internet.

Upon the proposed ban, we asked five experts how a nationalist approach to platform governance could impact the digital economy. This article compiles their responses.

Susan Ariel Aaronson, the Centre for International Governance Innovation

There are two issues colouring US response to Chinese platforms: economics and national security. Regarding economics, China’s big platforms grew up under the Great Firewall, where they were protected and nurtured. With economies of scale and scope for data, the firms learned to excel in data-driven services and compete effectively in more open markets such as Canada and the United States. Regarding national security, China is good at stealing and, buying data legally, as well as buying data-rich firms and creating apps that acquire personal data. China can use that data, cross data sets and gain new insights into behaviour of Americans, creating a national security threat.

Given #trump on #tiktok and #wechat, don't be surprised to see countries ban #facebook for national security or #socialstability concerns regarding their manipulation of #personal data. https://t.co/kauTNx46CN

— Dr. Susan Ariel Aaronson (@AaronsonSusan) September 21, 2020

What is the appropriate response? First, the Great Firewall must be challenged as a trade barrier (an international response). It also reduces competition among ideas, which are a public good. The Great Firewall hurts China and Chinese people, who have less access to information. Governments should also go after firms that supply infrastructure for the Great Firewall. Second, the United States needs a national online personal data protection law. The US people have little control over how their data is used and monetized. Finally, app companies need to effectively monitor app stores. Google, Microsoft, Garmin, Apple, etc., all fail to adequately review apps to make sure they are only taking the data that is essential to app function. The United States and other countries need laws limiting how apps can take and utilize personal data.

Anupam Chander, Georgetown University

I did not think we would ever see a Great Firewall of America, but that is what the Trump administration has brought us. The capricious TikTok/WeChat bans will serve as a terrible precedent. The US demanded data localization as a price of TikTok’s continued operation in the United States, but it went even further — demanding that it be majority-owned by Americans. If other nations borrow this precedent, it will be the American social media and communications companies that suffer, as our own intelligence services have been known for mass hoovering up of data (although our laws have improved somewhat — while other nations’ surveillance agencies often have few legal restraints). Our actions will serve as a poor precedent for others, inviting them to further break up the internet into national domains. The actions against TikTok and WeChat were largely motivated by domestic political objectives — allowing the Trump administration to distract from domestic calamities by pointing fingers at a foreign villain. A better solution is to have a legal framework that protects fundamental rights to privacy, security and speech, regardless of where data flows.

My key takeaway re: #TikTokBan--next time reporters shouldn't readily devour claims of imminent national security threats justifying radical action that happens to coincide with authorities' interests. National security has been the basis for the rise of probably every despot.

— 😷Anupam Chander (@AnupamChander) September 19, 2020

Robert Fay, the Centre for International Governance Innovation

The actions the United States is taking against TikTok and WeCom [Tencent’s quick rebrand of WeChat to avoid the looming ban] under the guise of national security have perhaps unintentionally highlighted an extremely important global issue: the lack of effective governance over the use and monetization of personal data. Of course, because these actions are directed toward China, it is more about technological supremacy and how data can be used to generate valuable intellectual property and wealth, such as the underlying algorithms that drive the social media platforms. Instead, we need to take a globally comprehensive approach to data governance that breaks down barriers, including the Great Firewall, and addresses the very valid concerns over how personal data may be used. This includes not only those in China but also those in the United States. Instead of ad hoc actions, we need global rules. It is time for a Digital Stability Board.

Dipayan Ghosh, the Berkman Klein Center

This is the splinternet happening before our eyes. We are seeing three divergent approaches to internet governance take shape — with the Chinese system epitomized by state control, the European system focused on individual rights and, finally, an American one that over time has evolved from open capitalism to something that looks increasingly protective of domestic economic interests, thanks to President Trump’s political motivations. That is the key: given the absence of any clear evidence that TikTok has shared US user data with Chinese authorities, the administration’s decision appears to be political — and we can expect China to throw its own economic attacks at the United States in response. The good news for the interests of global internet governance is that because the decision does have Trump’s electoral politics written all over it, a more general policy shift can easily be reconsidered by a more stable and transparent administration if and when political circumstances shift — although it appears as though the TikTok split-up will move forward at this stage, and this will no doubt irk the Chinese government.

The bans illustrate that privacy and security matter, and will strengthen the argument that if tech firms don’t get privacy and user rights right, then they’ll be subject to stringent regulation that every company—@facebook and @google included—will have to comply with.

— Dipayan Ghosh (@ghoshd7) September 18, 2020

Blayne Haggart, the Centre for International Governance Innovation

The actual decision to ban TikTok and WeChat downloads is little more than capricious grandstanding by an incompetent administration that barely understands the games it’s playing. The irony is that internet governance has tended to reflect the interests of the United States and its companies, namely, global market dominance. “Net nationalism” is often merely an acknowledgement that this type of governance does not always suit non-dominant countries. The term also hides the extent to which the current regime promotes the national interests of dominant (mostly American) players. To be blunt, such an overt display of dominance is pure foolishness coming from the world’s leading digital economy, whose power lies in the promotion of the idea of a free and open internet, not in bullying foreign companies out of its market, or in shaking them down to give American companies a piece of the action. It can’t help but hasten the trend toward an internet that less reflects US strategic interests. But it’s also par for the course for an administration that has consistently failed to understand that the United States’ true power lies in its promotion of open borders, for trade and data.

At the end of the day, the TikTok/WeChat debacle is a distraction from the longer-term challenge of national digital-economic competition. The United States, China and the European Union, to name only the biggest players, all have different ideas about how the global digital economy should be run. This is an issue that predates Trump and will long outlast him.