As digital data has become more important in our technoscientific economies, it is increasingly understood and treated as an economic asset that holds significant value for businesses, governments and citizens (Birch 2023). More than a decade ago, for example, the World Economic Forum (2011) specifically characterized personal data as a “new asset class.” Since then, it is possible to trace how data has been reframed and transformed into an economic asset. Despite the ongoing assetization of data, however, it is still difficult to define and unpack the economic and social value of data, which raises a number of social and policy implications for data governance.

Despite these difficulties, there has been considerable interest over the last few years in standardizing the economic understanding, treatment and governance of digital data. Several international institutions, including the United Nations, the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development and the European Commission, are revising the System of National Accounts (SNA) to incorporate data and its value into national economic indicators. The SNA is a set of national accounting standards used by countries around the world to standardize and harmonize their economic statistics and forecasts. These standards configure how countries define and estimate indicators, such as GDP and capital investment. A major revision to the SNA will be released in 2025, and it will include a new standard for the treatment of digital data as an asset (Mitchell and Lesher 2021).

As a result of these international standardization efforts, it is an opportune time to consider new policy initiatives, mechanisms and instruments for governing digital data. Countries will increasingly treat data as an economic and strategic asset, and this will have knock-on effects across our economies and societies as policy makers, businesses and citizens rethink their understandings and treatments of data and the economic and social benefits from its collection and analysis. These changes will inevitably lead to growing demand for transparency around who controls and benefits from data, especially personal data; for example, businesses will need to work out how to record data on their balance sheets — something they have not had to do to date (Birch, Cochrane and Ward 2021). Consequently, it will become clearer where data sits, who controls access to it and who benefits from that control; at the same time, this increased transparency will lead to growing demands for changes to the way that data is governed.

Data as an Economic Object

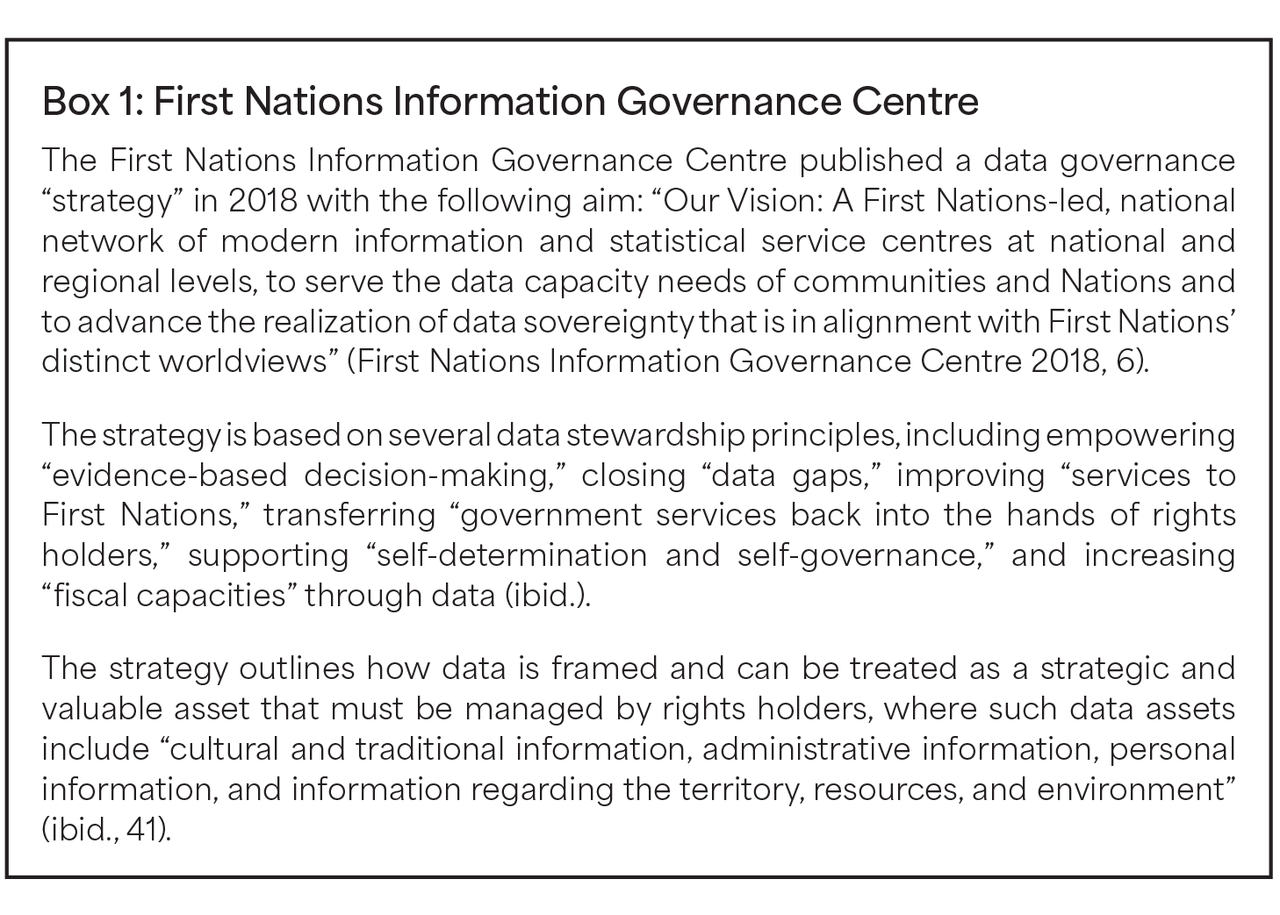

Digital data is an economic object that has value. But data does not fit neatly into prevailing definitions of goods or services. Rather, data is increasingly conceptualized and framed as a resource, and specifically as an economic asset (Birch, Cochrane and Ward 2021; Birch, Marquis and Silva 2024). For example, the Government of Ontario has an ongoing strategy to build a “Digital Ontario” on this basis, stating: “Data has become one of the world’s most valuable assets. In 2018 alone, it added over $150 billion in value to Canada’s economy. Data powers Ontario’s government, its businesses, and its communities.”1 The framing of data as an asset is evident across a range of strategies, discussions and tool kits developed by various social actors, including businesses, policy makers and civil society organizations (see Box 1, for example).

Defining digital data as an economic asset entails thinking about data’s particular characteristics (Coyle et al. 2020; Mitchell and Lesher 2021; Birch 2023). Data is characterized as a non-rivalrous good, in that it can be used by several people at once. However, data is still excludable, in that data’s collection, storage and use can entail significant financial investment, which precludes its collection and use by everyone. Moreover, as facts, data is not subject to conventional intellectual property (IP) regimes, but businesses can still treat data as an asset by controlling access to it (Cohen 2019). Finally, data assets have emergent properties, in that their use and value are an effect of data’s aggregation and the relationship between multiple data points; consequently, their usefulness and value are more than a simple sum of their parts (Esayas 2017; Viljoen 2021).

These characteristics mean that it is difficult to calculate and measure the value of data as an asset. International economic standards setters, such as the SNA, have been developing an approach based on a sum-of-costs method, which defines the data value as the cost of its production (for example, labour costs, equipment costs and so forth). An important assumption underpinning the SNA’s treatment of data is that data is a “produced asset,” meaning that data will be treated as if it is the result of organizational decisions akin to a range of other intangible assets (for example, IP) (Mitchell and Lesher 2021). However, these conceptual and measurement discussions can miss important conceptual and policy implications of data’s characteristics. As Salomé Viljoen (2021) notes, the value of data comes from its relational and collective configuration; that is, data has economic and social value precisely when it is brought together in collective data holdings, combining data from multiple people or organizations to generate new inferential and other insights. These insights depend upon data’s emergent properties, in that the combination of data creates outcomes or outputs that cannot be foreseen by a summing of the parts.

We need a new data governance regime to address these paradoxes and ensure that the benefits of digital data are shared by everyone rather than primarily by a few multinational businesses.

As an asset, digital data is consequently difficult to value and to govern. It is increasingly evident that current data governance regimes entail a series of contradictions, even paradoxes, when it comes to the use and value of data. First, data is an important and valuable resource for the twenty-first century, but there is currently little agreement on how to measure or calculate its value. Second, data has considerable social value, especially because of its non-rivalrous qualities, which means diverse data sets can be combined to stimulate widespread innovation; however, data governance regimes do not stop organizations or individuals from making data excludable, thereby limiting innovation and ensuring that only a few entities (for example, big tech) benefit from these combinations. Last, the wider social benefits and value of data depend upon sharing it, but the economic value of data depends upon restricting access to it (Birch 2023).

We need a new data governance regime to address these paradoxes and ensure that the benefits of digital data are shared by everyone rather than primarily by a few multinational businesses.

Data Governance

Debates about digital data governance have been ongoing for a while and cover an array of possible approaches (Micheli et al. 2020). The reason for this is because data is increasingly identified as a valuable asset that a few large multinational businesses — usually defined as big tech — have claimed for free, despite data being the collective product or output of everyone’s digital activities (for example, using smartphones, using social media, using search engines). Yanis Varoufakis (2024), the ex-finance minister of Greece and heterodox economics professor, calls this a system of “technofeudalism” in which most people labour away as “cloud serfs” generating the resources and assets that “cloud capitalists” take to generate their revenues. A less poetic way to think about this is to consider personal data as an economic rent that businesses extract from our lives, behaviours and decisions (Birch, Chiappetta and Artyushina 2020).

Data governance approaches have been developed to address these concerns. Such governance approaches can be split into three main philosophical camps. Viljoen (2020) defines two camps as “propertarian” and “dignitarian,” while Barbara Prainsack (2019) defines a third camp as “solidaristic.” Propertarians include thinkers who want to extend individual property rights to data, especially personal data. According to these thinkers, data could be treated as IP that can be claimed by the identifiable person it relates to (Lanier 2014), or data could be treated as the product of people’s work (Posner and Weyl 2019), harking back to the seventeenth-century philosopher Thomas Hobbes. Propertarians think that individuals should gain direct personal benefit from their data. Dignitarians include thinkers who consider personal data to be a human right and therefore want to limit its commodification and assetization in order to preserve privacy and democracy (Zuboff 2019). While the propertarian and dignitarian camps are certainly noteworthy, providing helpful insights into current data governance regimes, they both tend to naturalize individualistic framings of data governance.

The third, solidaristic, camp offers a more optimistic and compatible way to rethink and restructure data governance in light of data’s increasing treatment as an asset, especially as a collectively generated resource. As Prainsack (2019) explains, a good starting point for understanding data is to consider it like other “common” resources; commons can be easily undermined when we rely upon individualistic governance mechanisms (for example, markets, individual rights) in which there are serious and significant power asymmetries between social actors (for example, between an individual and a multinational). Instead, thinking of data as a common resource highlights the need to create an individual and collective governance mechanism, in order to protect individual and collective rights and the social benefits that accrue from the collective sharing of data. Solidaristic politics can support both the sharing of data and the economic and social benefits that sharing brings, as well as ensuring that those benefits are distributed equitably.

It is vital to find the right organizational structures and mechanisms to support the solidaristic understanding of data governance. There are several options proposed by a range of different social actors. However, the proposal in this essay is for the establishment of a data wealth fund (DWF) that combines the treatment of data as an asset with the solidaristic politics of understanding data as a collectively generated and commonly held resource.

DWF

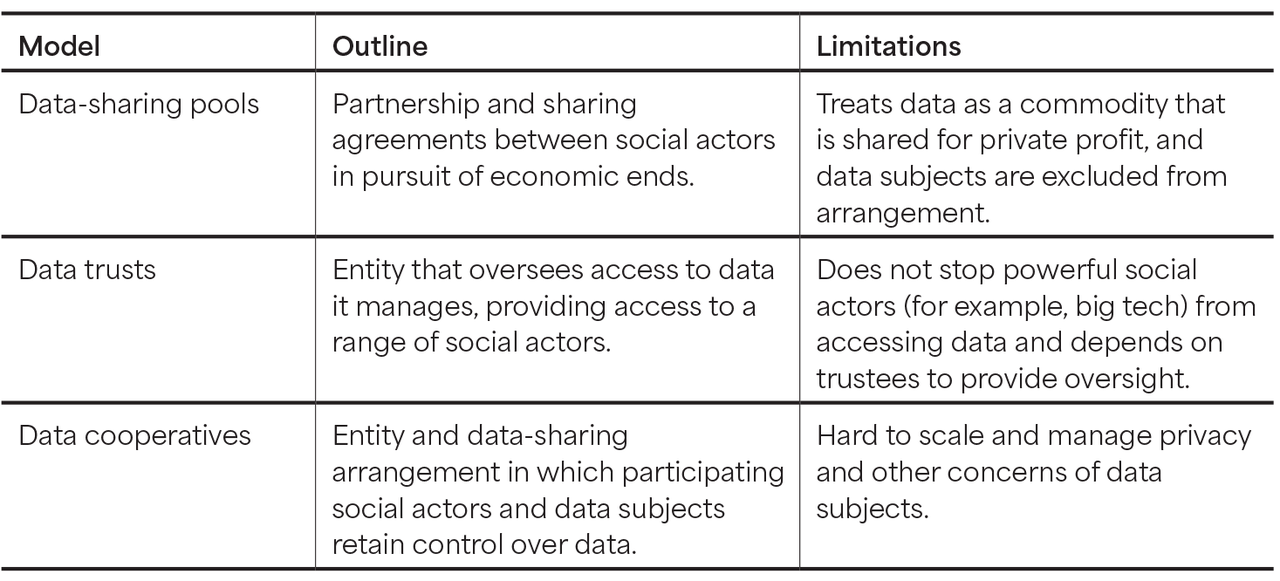

There is a range of digital data governance models that fit with this solidaristic position, many of which have been developed over the last few years in response to growing concerns about the collection, use and exploitation of data by multinational businesses (i.e., big tech). Examples of these data governance models are outlined in Table 1, which also includes some of the limitations of each model.

Table 1: Data Governance Models

It is important to consider alternative models of data governance in light of these limitations. One alternative, which reflects the solidaristic idea of data assets as collectively generated and commonly held resources (Prainsack 2019), is the concept of a DWF.2 A DWF would copy some of the organizational operations and structure of other resource funds, such as oil and gas funds run by national governments. An example is Norway’s “Oil Fund,” which was established in 1990 as part of a strategy to diversify Norway’s economy and make it more resilient to changing oil and gas prices, as well as to other global economic shocks. The Oil Fund currently represents more than $2 trillion in a portfolio of assets from around the world. The fund receives billions of dollars each year from taxation, fees and government ownership shares in the oil and gas fields.3

The concept of a DWF is based on an understanding of digital data as a collectively generated and commonly held resource or asset, in that data represents aggregated information about a population that the population produces through its actions, and the data has value precisely because of its relational and emergent qualities directly derived from that population. A DWF is a governance model that ensures a country’s data is used in ways that its residents want and derives a share of the value that the data generates for its users, especially for businesses. While copying other wealth funds, the DWF would require new organizational operations and structures to support the underlying principles for any data governance framework. These underlying principles could be:

- to protect the privacy of a country’s residents by coordinating and managing access to and the use of the country’s data, including government, health and personal data;4

- to encourage the sharing of a country’s data in support of digital innovation across business, government and civil society;

- to ensure that a country’s residents benefit from the sharing and use of a country’s data through taxation, fees and ownership shares; and

- to hold users of a country’s data to account for their use of data, especially through public engagement initiatives to establish what a country’s residents would like their data to be used for.

Eventually, a DWF could become the data steward for a country’s data (Cameron 2024), being responsible and accountable for the data collected about a country’s population. It would be a national and publicly managed entity, independent of government but accountable to a country’s residents through public engagement processes. It would collect, store and hold data, which could be accessed by different social actors on a differential fee basis, depending upon criteria such as the direct social benefits expected and the direct private benefits received. It would necessitate regulation requiring that any data-collecting entity must deposit said data in the DWF, with fines imposed if an entity fails to comply. Operationally, this requirement to deposit could follow a terms and conditions agreement requesting data, HTTP cookies or a similar declaration of data collection — that is, if an entity makes a request for data through these means (or others), then it would be required to deposit that data in the DWF. Through this requirement to deposit, any entity could be held accountable for data deposit.

Unlike other wealth funds, there are a range of distinct issues that any DWF would have to address in its operations and structures to be functional. A few issues that any policy maker would need to address would include:

- Data heterogeneity: Most wealth funds generate revenues from one or two well-known and often fungible non-produced assets (for example, oil and gas); however, digital data is often heterogeneous in origin and function. A DWF would need to ensure that it has a clear definition of digital data and that it has a specific set of requirements for diverse entities (for example, businesses, hospitals, governments, civil society organizations and so forth) on what data they are required to deposit. This might mean that internal operational data is not covered by the requirement to deposit unless the data includes personal information.

- Policy intervention: Digital data is different in that it is increasingly framed as a produced asset, resulting from the action of specific entities generating it. A DWF would need to ensure that the digital observing, recording and storing of information (as data) is the focus of policy intervention, rather than the produced asset itself.

- Administrative entity: Digital data is collected and aggregated by a range of public administrative entities such as national statistical offices (NSOs). A DWF could be built out from an existing NSO since these entities have existing operational capacities to collect data, permit access and disseminate according to established principles.

- Tensions with open data: As strategic assets, governments and policy makers increasingly seek to open up public data holdings. A DWF would have to balance the societal benefits of open data versus charging for access to its data holdings.

From 2025, data will be increasingly treated as an economic asset, and this shifting attitude will ripple across our economies and societies. Although it is difficult to predict the effects of this change, it is still important to consider its implications for data governance. In particular, it is clear that the importance of data will only grow, in light of the ongoing boom in interest in artificial intelligence technologies. How we handle data, then, is critical for societies. Returning to outdated and downright problematic governance frameworks based on notions of naturalized markets is not viable anymore; we need to take a more concerted, collective approach to data governance that can address the paradoxes emerging in the data economy. For the author, solidaristic principles underpinning a DWF are one option that tries to deal with these paradoxes and attempts to spread the benefits of the data economy beyond a few big tech firms and their investors.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Bob Fay, Jenny Thiel and Andy Best for their feedback and advice. The research underpinning this essay was funded by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (Ref. 435-2023-0704).