The wiring and rewiring of the African continent offers a unique vantage point to understand existing and future tensions between state and corporate actors seeking to extend their influence on a global scale. These tensions are being increasingly described with hyperbolic tones as part of an emerging “Cold War” between two digital superpowers — China and the United States — battling to advance their competing ideas of the information society.

The Cold War trope, however, is both inaccurate and distracting. It conceals how in most African countries, digital infrastructures have evolved — and are continuing to evolve — by combining material artifacts, solutions and ideas from the West and from the East, in stark contrast with the expectation that nations should choose one camp or the other. More importantly, it prevents an appreciation of the technological imageries and materialities that have progressively emerged within the African continent, acquiring momentum and often defying simplistic narratives.

Most African governments and service providers have scoffed at then US President Donald Trump’s ban on Huawei, subsequently renewing or signing new contracts to expand national backbone infrastructures, implementing solutions in urban surveillance and launching 5G networks with Chinese companies (Prinsloo 2020). These reactions have little to do with supposed new allegiances to China and its “model” of the internet. Rather, they reflect greater confidence in developing specific strategies for digital innovation, where foreign partners may indeed be recognized as more resourceful but are brought in to implement those strategies rather than impose their own.

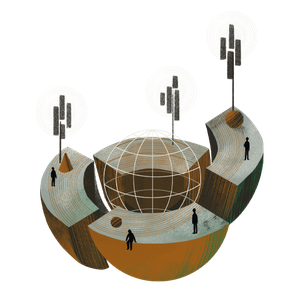

Similarly, Facebook and Google have put much spin on their unprecedented initiatives to increase Africa’s connectivity, building the two largest undersea cables around the continent (2Africa and Equiano), which are expected to dock and become operational by 2024. Facebook resorted to tired tropes about Africa as “the least connected continent” (Ahmad and Salvadori 2020, emphasis added), promising to deliver “the most comprehensive subsea cable” (ibid., emphasis added) to stress the significance and benevolence of its operation (and reaffirming the company’s obsession with size, ironically captured by artist Ben Grosser in his video “Order of Magnitude”1).

Is it goodwill that is powering up these newest attempts to wire Africa?

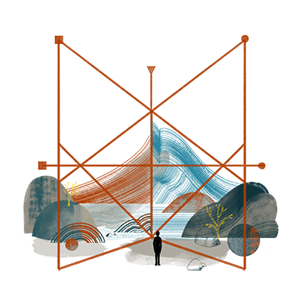

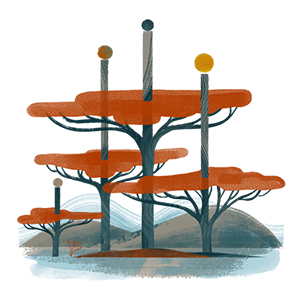

These statements are apparently oblivious of two important precedents in the history of digital connectivity in Africa. The first, and more recent, is how before resorting to “bricks and mortar” solutions such as undersea cables, the same companies had tried other avenues to connect the unconnected that were more aligned with the “disruptive” ethos of Silicon Valley. Facebook’s Aquila bet on solar-powered drones as relay stations to provide internet in remote areas. Google’s Loon relied on a fleet of balloons to achieve similar goals. Both projects were shut down after a few years. It is interesting — and possibly revealing of broader limitations in interfacing with the continent — how both solutions were designed to beam their services from above, minimally intersecting with the complex socio-political realities of Africa’s information societies. The second partial omission is how 2Africa and Equiano add to a long list of pre-existing undersea cables, funded either by a consortia of African governments and service providers, that were built when connectivity and digital interactions in Africa were still perceived as relatively unprofitable (for example, Seacom, the Eastern Africa Submarine Cable System), or by China as part of its digital Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) (for example, the Pakistan and East Africa Connecting Europe submarine cable). This longer-term perspective sheds a different light on Google’s and Facebook’s initiatives — as well as on China’s. Is it goodwill that is powering up these newest attempts to wire Africa? Or are African nations in a position of unprecedented strength, appealing to tech giants as the last digital frontier, but also potentially able to play the competition and set new rules of the game?

Western Promises and Chinese Anxieties

The rise of Chinese tech firms in Africa has been often associated with a sense of fear and anxiety, powered by the concern that China may seek to export its model of the information society, favour authoritarian tendencies in the shaping of digital spaces or promote its interests in a covert form. This narrative has emerged in opposition to one associated with ideas of hope and opportunity, located in a different time, when the internet started becoming a global phenomenon, and in a different space, progressively expanding from its epicentre in the United States.

As with all narratives, these two narratives are revealing and concealing at the same time. They are rooted in objects, events and processes that have relatively clear referents (for example, the arrest of a digital activist, the toppling of a dictator) and, at the same time, have the power to evoke other objects, events and processes by association. They also acquire or lose momentum at different points in time, as new elements emerge, either reinforcing or contradicting those that are considered more central or foundational.

It is in this regard that these two narratives have followed different trajectories in the past few years. The image of digital technologies as “liberation technologies,” capable of freeing the world from abuse and dictators, has been eroded by the capacity of power to retain or claw back control (for example, the endurance of authoritarian leaders in Cameroon, China or Russia, or the political fallout of the Arab Spring); scandals (for example, Cambridge Analytica); leaks (for example, Snowden); and the heightened attention and reporting of hate speech and mis- and disinformation.

In contrast, the narrative of “technologies of unfreedom” — empowering the powerful, making surveillance pervasive and expanding globally from an epicentre many would locate in China — has gained new strength. Is it worth asking, however, whether this latter narrative is tied to a specific conjuncture. Does its relative strength preclude fully appreciating elements or phenomena already at work that may ultimately prevent feared (or desired) consequences from materializing?

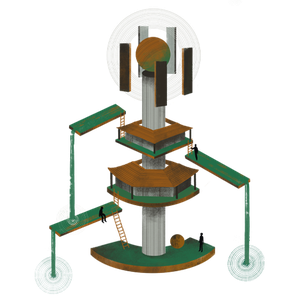

An example can clarify this point. Much attention has been placed in the past few years on the deployment of Huawei’s Safe City and ZTE’s Smart City projects in Africa and globally. The urban surveillance solutions developed by the two Chinese companies are layered and relatively distinct, but they both rely, in essence, on operation centres analyzing vast amounts of data in real time, sourced from sensors and cameras deployed across the city (Artigas 2019). They offer services ranging from mundane smart metering to more worrying emergency assessments aimed at keeping “social peace” and predictive policing. Their deployment across the globe has been received with a sense of moral panic, stressing how Huawei’s and ZTE’s solutions represent a threat to civil liberties. These services certainly have the ingredients for being so. These reactions, however, seem to presuppose that surveillance technologies, somehow aided by their more sinister and cunning nature, will succeed in producing their desired effects where liberation technologies failed.

Data emerging from Asia and Africa, however, has begun to reveal how Huawei’s own promises of curbing crime and improving centralized city management clash with the (quite predictable) complexity of the socio-political and technological realities of different locales. Reports from Pakistan, one of the main beneficiaries of China’s BRI, indicate that, after a slight reduction in the year following the installation of Huawei’s Safe City in the country’s major urban centres, violent crime has continued to rise (Hao 2019). As Nicole Hao reported, “Huawei claimed that the endeavour would dramatically improve order, with a projected 15 percent reduction in violent crime. But while crime in Islamabad did fall in 2016, by the end of 2018, it had increased by 33 percent” (ibid.). Kenya, an early African adopter of Huawei’s Safe City, experienced a similar trajectory, with crime rates apparently unaffected by the installation of new surveillance technologies in Nairobi and Mombasa (Prasso 2019).

These failures should not be surprising. The hype surrounding surveillance technologies (as it happens for most innovations framed as “disruptive”) and the scare provoked by the fact that these technologies are emerging from China, have led to overlooking how every artifact is part of wider networks, which profoundly influence its functioning. As much as in the past, the promises of liberation technologies to free the world from abuse and dictators have been challenged by the actual interaction of these technologies with existing networks of power and politics. New surveillance technologies are running into a similar risk of faltering or failing when inserted into contexts that are very different from those where they originated. The “successes” recorded by Safe City and Smart City when deployed in China are due, in part, to the technological solutions developed by Huawei and ZTE; they also depend on larger networks made by norms, bureaucracies and policies, which significantly affect the outcomes these technologies produce.