The past few years have not been kind to businesses in China. While the country was still recovering from its trade war with the United States in 2019, economic activities were halted across the country in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Then the government launched massive crackdowns in several sectors in 2021, with the business environment further worsened by the draconian zero-COVID policy in 2022.

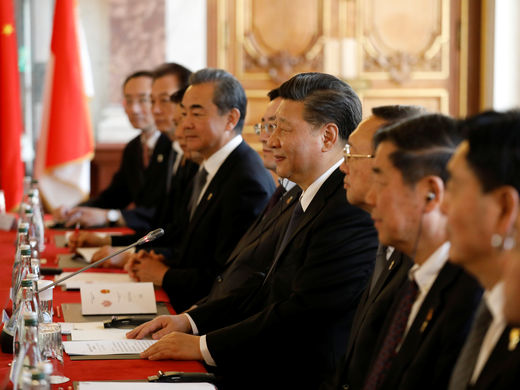

Signs of a shift were apparent at the turn of the year, after President Xi Jinping secured an unprecedented third term at the 20th National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) in October 2022. First, in December, China made a sudden U-turn on its zero-COVID policy. Then several senior officials announced the conclusion of the investigations on tech companies, prompting major international media such as The Wall Street Journal to declare the end of China’s two-year tech crackdown.

But is the regulatory crackdown really over? Will China’s economic policy return to business as usual? While it is always hard to predict the future, we can catch a glimpse of the potential directions of China’s regulatory and economic policies in 2023 from some of Xi’s recent speeches and policy moves.

Xi’s Party Congress Report at the 20th National Party Congress provides the most comprehensive summary of his economic and regulatory visions. According to that report, the main task for China for the next three decades is to achieve so-called Chinese-style modernization, further defined as socialist modernization led by the CCP.

The primary task in achieving this, Xi’s report states, is to promote “high-quality” development that would require the joint efforts of both state-owned enterprises (SOEs) and private enterprises. However, the report made clear that the two will be playing quite different roles. On the one hand, the state will promote SOEs to “become stronger, better and bigger”; on the other hand, private enterprises can only expect that their interests and rights will be “protected in accordance with the law.” The implicit message here is that, to the extent private enterprises do not carry on their activities in accordance with the law, their interests may not be protected.

Unfortunately, China’s incomplete transition to a market economy means regulations often lag behind the demands of the market, forcing many private enterprises to operate in legal grey areas before an activity is formally legalized. This is not a problem when the economy is booming and everyone is looking forward, but it could become a major issue when the economy stagnates and political scapegoats are needed.

A good example in this regard is Alibaba. While Alibaba has been providing third-party payment services from as early as 2004, it did not receive the necessary licence until seven years later, when China first introduced rules regulating such services. This was not a problem at a time when China needed Alibaba to grow its non-existent payment business. But when Alibaba founder Jack Ma became too noisy for Beijing’s comfort, 10 years later, the fact that his company had not conducted business “in accordance with the law” quickly attracted the attention of regulators in the crackdown that ensued.

This bias for heavy industrial development is reaffirmed by Xi’s party congress report, which emphasizes that the key focus of economic development should be the “real” economy, that is, only the industrial and agricultural sectors.

The ambiguous attitude toward private firms is also reflected in the repeated reference in the report on the need to “guide the healthy development” of private enterprises and capital, an elusive concept that changes as rapidly as fashion. In July 2001, a few months before China’s formal accession to the World Trade Organization, then president and CCP general secretary Jiang Zemin announced at the meeting celebrating the party’s eightieth anniversary that even private entrepreneurs are “builders of socialism with Chinese characteristics” and thus should be welcomed into the party.

Since then, promoting the development of private firms has become a major component of the key performance indicators for CCP officials. Premier Li Keqiang even earned the nickname of “super salesman” for Chinese firms when he first came into office in 2013. However, 10 years later, the tone has changed completely, as evident when Xi delivered the icy warning in his party congress report that leading cadres should not become “the spokespersons and agents of interest groups and powerful groups” and that “the problems of political and business collusion that destroys the political ecology and economic development environment” would never be tolerated.

Paradoxically, the highly amorphous regulatory environment in which China’s private firms find themselves means they often must rely on political connections to get things done.

In good times, this is regarded as an example of government officials and private entrepreneurs working hand in hand to build “socialism with Chinese characteristics.” When things go wrong, however, this could well be deemed as “political-business collusion.” The latest example is the recent disappearance of Chinese venture capital tycoon Bao Fan. Widely regarded as the leading “capital matchmaker” in China, Bao’s name is closely linked with the key funding rounds and merger deals of almost all Chinese digital giants.

While these deals were lauded when they were made a decade ago, they now appear to be much less appealing under the newly calibrated regulatory microscope. More broadly, the types of businesses pursued by digital giants such as Alibaba are now regarded as “unhealthy,” or more specifically, not in line with the industrial policies of China. This portrayal is well illustrated by the controversy surrounding community group buying of groceries, which saw a huge surge in 2020 when China’s digital platforms rushed to meet the needs of residents who struggled to shop for groceries in endless waves of COVID lockdowns that grounded everyone in their apartments and closed supermarkets. However, for the mandarins who never had to worry about food shortages even during the pandemic, this seemed to be a terrible waste of the vast data and financial resources of the digital giants. Instead, as a People’s Daily editorial made clear, digital platforms should “stop tallying the revenue from a few bundles of cabbages and a few catties of fruits, and start fathoming the stars and seas of scientific and technological innovation, and the infinite possibilities of the future.”

This bias for heavy industrial development is reaffirmed by Xi’s party congress report, which emphasizes that the key focus of economic development should be the “real” economy, that is, only the industrial and agricultural sectors. The tertiary sector — services — is almost ignored in his report. When mentioned, it is only considered to be a supplementary activity “deeply integrated with advanced manufacturing and modern agriculture.”

So what do all these developments tell us about China’s economic and regulatory policies in the months ahead?

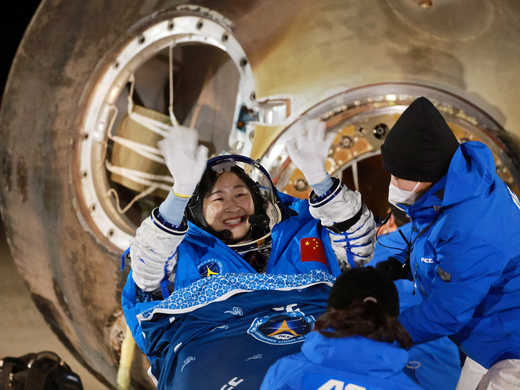

First, the heavy focus on industrial development will continue. As Xi announced in his speech at the Central Economic Work Conference held in Beijing in mid-December 2022, China shall “comprehensively improve the modernization level of the industrial system, which not only consolidates the leading position of traditional advantageous industries, but also creates new competitive advantages.”

“Traditional advantageous industries” refers to the manufacturing sector, which is heavily dominated by SOEs. “New competitive advantages” refers to strategic emerging industries such as new energy, artificial intelligence (AI), bio-manufacturing, sustainable development and quantum computing. Here, Xi called for more investment by tech firms and digital firms. If a firm is able to catch the wave, it will become the darling of both the market and the government, potentially pocketing billions in government subsidies. However, as the recent debate on the development of a ChatGPT-like AI platform in China has shown, it might be quite difficult for Chinese tech firms to catch up, due to China’s restrictive censorship regime and data policies.

Second, the regulatory crackdown is unlikely to end; on the contrary, it is likely to spread to sectors beyond the tech industry, especially in finance. This move was hinted at in Xi’s speech at the Central Economic Work Conference, where he noted that “finance matters to the overall development. It is necessary to coordinate the prevention of major financial risks and moral hazards, consolidate the responsibilities of all parties, deal with them in a timely manner, and prevent the formation of regional and systemic financial risks. It is necessary to strengthen the centralized and unified leadership of the Party Central Committee on financial work and deepen the reform of the financial system.”

As the government headed by Li Keqiang bows out after it concludes the second term in March, there will be many seats at various agencies in the central government waiting to be filled. A key piece of this reshuffling will take place among the financial regulators, and whoever comes in will try to demonstrate loyalty to Xi by faithfully carrying out his drive against the trend of what Xi calls “elitism,” disguised as “marketisation” and “professionalisation,” plaguing the financial industry.

As demonstrated by the recent prosecution of former China Merchant Bank president Tian Huiyu, a major part of the investigation will concern problematic loans, especially those to private firms. This will make it even harder for private firms to obtain loans than before, unless such applications are backed up by business plans in line with China’s industrial policy.

This is where China’s regulatory crackdown will kill two birds with one stone. It will both ensure the further dominance of SOEs, and force private firms to align their businesses with Xi’s vision of Chinese-style modernization: a Soviet-style industrialization plan focusing on heavy industrial development.