Authoritarianism and its various practitioners are frequently invoked as a collective threat to democracies across the globe, Canada included. At its most basic, the label “authoritarian” applies to countries that have rejected political pluralism in favour of concentrated and centralized power. Underneath this broad umbrella, authoritarian regimes come in all shapes and sizes, from military juntas to personalist dictatorships. The People’s Republic of China, Saudi Arabia and Russia, for example, all certainly qualify, yet despite fundamental differences between these regimes, they are often lumped together and cast as an omnibus (albeit amorphous) challenge to Canada and to like-minded democracies.

What follows examines how challenges from authoritarian states have shaped the trajectory of Canadian foreign policy over the course of the twentieth century. At various points, Canadians organized themselves — marshalled their political, economic and military resources — to stand against Prussian militarism, fight Nazi and fascist aggression, and guard against the threat of communist incursion. Successive governments in Ottawa did so, motivated in large part by a desire to defend their own political system against the dangers posed by various authoritarian challengers. Authoritarian states, as a result, provided a sort of organizing logic that framed Canada’s foreign policy and the central objectives thereof for much of the twentieth century.

Not every authoritarian state has presented Canada with an existential challenge. The threats, both real and perceived, that defined the First World War, the Second World War and the Cold War determined the geopolitical landscape of much of the twentieth century but, in the grand scheme of Canada’s engagement with authoritarian states, they were statistical outliers. More often, Canada’s relations with authoritarian regimes have revolved around questions of how and on what terms Ottawa should engage them. Canadian governments faced perennial dilemmas about how to balance their desire to promote the tenets of democracy, such as freedom of speech or human rights, against other priorities, including trade ties and stable and productive diplomatic relations.

More often, Canada’s relations with authoritarian regimes have revolved around questions of how and on what terms Ottawa should engage them.

In the summer of 1914, a crisis broke out in the Balkans, triggered by the assassination of the heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne, Archduke Franz Ferdinand. Austria-Hungary responded, declaring war against Serbia. Bit by bit, a web of alliances and alignments drew the powers of Europe into conflict, with Russian, French and German declarations of war following in rapid succession. The government in London, fearful that Germany might come to dominate Europe, soon joined in, bringing with it the British Empire, including Canada.

London touted its involvement in the war as an endeavour “to save the freedom of the people in all Europe” and to defend them against the imposition of the German way of life. “In Germany,” one war poster declared, “the Emperor rules, the people have no power, there is no free speech. The military class does what it likes.” Should the Germans be victorious, it was that system that would win out and “the cause of freedom and equal justice and fair play for you will be gone for hundreds of years.”1 That rhetoric resonated with a great many Canadians who saw London’s cause as their own. “The democracies of Greater Britain stand together in all parts of the world to support the traditions of British liberty,” the historian George Wrong insisted (McKercher 2019, 60).

But there lay a profound disconnect between the stated aims of defending liberty abroad and the day-to-day realities of what the Canadian war effort entailed at home. Under the terms of the War Measures Act of 1914, the federal government could suspend habeas corpus, intern suspected “enemy aliens,” ban various political organizations and introduce wide-ranging censorship measures to restrict speech. The tools deemed necessary to defend democracy in times of war could — and did — come at the cost of many of those same democratic freedoms. Indeed, successive generations in power in Ottawa have struggled to protect the freedoms and liberties of their democratic system against the dangers of easily exploited elements of the very system they hoped to defend.

In the wake of the Great War, Canadians threw themselves into the work of avoiding another global conflict. Prominent and high-profile citizens, including former prime minister Sir Robert Borden, launched the Canadian Institute of International Affairs in 1928. And the late 1920s saw a boom in organizations dedicated to the new multilateral forum, the League of Nations, with local League of Nations societies emerging from coast to coast.

A broad commitment to multilateralism and to the new structures of the post-1919 world did not automatically translate into a firm policy designed to rebuff those who hoped to revise and reorder that world. Throughout the 1930s, with capitalism in the doldrums of the Great Depression, other ideologies — and the authoritarian states that backed them — gained support across Europe and Asia and found adherents at home among Canadians.

The challenges of authoritarianism in the 1930s, whether arising from Nazi Germany, imperial Japan, fascist Italy or the communist Soviet Union, were met with a tepid response in Ottawa. When Japan moved against the resource-rich Chinese province of Manchuria in the autumn of 1931, for instance, Canadian observers argued over the national response. From the Canadian mission in Tokyo, Hugh Keenleyside denounced Japanese actions as an act of outright aggression. Japan might have had treaty rights in Manchuria, many of which had been violated by China, but those rights did not justify the use of force in response. Herbert Marler, Keenleyside’s superior, disagreed. The Japanese move had not changed the circumstances on the ground, given China’s already weak central government. Even if it were an act of aggression, Marler concluded that the great powers were unlikely to take action to stop it beyond a string of pious speeches at the League about the preservation of peace (Meehan 2004).

As Japan, Italy and Germany left the League of Nations and violated the restrictions imposed by the settlements of 1919, Ottawa maintained its diplomatic relationships. A Canadian delegation helmed by Minister of Trade William Euler and the diplomat Dana Wilgress concluded a bilateral trade agreement with the Germans against the backdrop of the 1936 Summer Olympics in Berlin. Two years later, the mass, state-sanctioned violence of Kristallnacht caused a growing segment of the Canadian population to lobby Ottawa to extend greater aid to Jews hoping to flee Nazi persecution. These pleas were rejected.

Even in early 1939, Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King remained convinced that war could be averted. “Appallingly critical as I know the whole situation to be,” the prime minister confided in his diary in January, “I cannot bring myself to believe that war will come between Germany and England.”2

King’s optimism proved unfounded. When war broke out in September 1939, countless Canadians rallied to the cause just as their forebears had in 1914. Once more, the struggles of war were cast in existential terms as a fight to defend the current system against its rivals and challengers. “Keep These Hands Off!” exhorted a broadside from the National War Finance Committee on an image of a mother and child surrounded by two menacing hands, one emblazoned with the swastika of Nazi Germany, the other with the rising sun of imperial Japan.

The end of the Second World War provided only the briefest respite. Before 1945 was through, the news of a Soviet spy ring operating in Canada’s midst rattled official Ottawa. Even the typically cautious King was convinced that Josef Stalin’s Soviet Union threatened the hard-won state of peace. “The rest of the world,” the prime minister concluded on March 5, 1946, reflecting on Winston Churchill’s now-famous Iron Curtain address in Fulton, Missouri, “is not in a very different position than other countries in Europe when Hitler had made up his mind to aim at the conquest of Europe.”3

In the face of such a threat, Canadian officials were determined to avoid the mistakes of the past by constructing a bulwark against the expansion of communist power spearheaded by the Soviet Union. Ottawa forged new political arrangements, such as the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, to deter Muscovite pressure.

As had been the case during both world wars, the Cold War was often described in stark terms. Its stakes were nothing short of protecting the freedoms and liberties enjoyed by Canadians and their counterparts throughout the West in the face of the grim alternatives offered by the Soviet Union. That rhetoric was not always compelling to Canadians, whether in or out of government. And as the Cold War stretched on, its urgency dissipated. Canadians worried about the excesses of anti-communism, whether on the part of their own government or, more often, by their allies south of the border.

These wars, both hot and cold, illustrate how a struggle against authoritarianism could give meaning and shape to the conduct of Canadian foreign policy. But in the broad sweep of the country’s history, these were the exceptions that proved the rule. For every Nazi Germany or Stalinist Soviet Union, there were countless other regimes deemed unsavoury, but not nearly as threatening to Canada or its interests.

In the day-to-day conduct of Canadian foreign relations, Liberal and Conservative governments alike have grappled with fundamental questions about how and on what terms to engage with authoritarian regimes of various persuasions. How could the government of the day, for instance, reconcile a desire to expand and sustain trade ties with the defence of broader principles such as human rights?

Attempts to strike a balance have defined Canada’s relations with a range of authoritarian states, from the Soviet Union and the People’s Republic of China to Iran and Saudi Arabia. Critics have lambasted various governments’ failures to calculate that balance correctly, highlighting the disconnect between Canada’s professed principles and its day-to-day decision making. Ottawa’s 2014 decision to export $15-billion worth of light armoured vehicles to Saudi Arabia, with its egregious human rights record, is a recent example. The satirical outlet, The Beaverton, pilloried the agreement, joking in one headline “Saudi Arabia condemns Canada’s appalling human rights record of selling arms to Saudi Arabia” (Field 2018). Tellingly, although the deal was initially approved by the Conservative government of Stephen Harper, the backlash mounted precipitously when Justin Trudeau’s Liberals took power, boasting of Canada’s return to the world stage (Toronto Star 2015) and the virtues of a feminist foreign policy (Vucetic 2017).

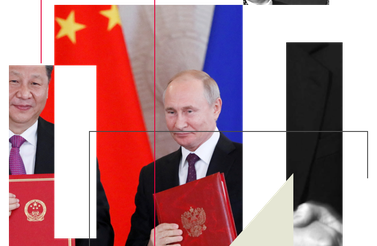

Perhaps nowhere have the trade-offs to balance these competing impulses been more visible than in Canada’s relations with China. As Prime Minister Jean Chrétien’s Team Canada pursued expanded trade with Beijing in the 1990s, his government studiously hoped to sidestep mention of China’s dismal record on human rights. On one occasion, Chrétien insisted that a country of Canada’s stature could not tell China how to behave at home. Size and relative influence shaped when and where Canadian governments felt emboldened to speak out in favour of their principles. Under Stephen Harper, for instance, the government denounced Iran’s human rights record and lobbied against Ugandan legislation to criminalize homosexuality (Chapnick and Kukucha 2016). Similar restrictions and persecution in Saudi Arabia went undiscussed. These dynamics continue to govern Canada’s policies toward China: in early 2021, when the House of Commons voted to label China’s treatment of the Uighurs a genocide, Trudeau’s Cabinet did not appear for the vote (Jones 2021).

Looking to the past does not offer any sort of how-to guide for Canadian policy makers to deal with authoritarian regimes. But the Canadian experience throughout the twentieth century and into the twenty-first does remind us of the perennial dilemmas at play.

The major conflicts that defined so much of Canada’s twentieth century — the First World War, the Second World War and the Cold War — put day-to-day problems facing generations of Canadian policy makers in the sharpest relief. Canadians defined their wartime efforts as nothing short of the defence of freedoms and liberties in a democratic system, and yet, to do so, also accommodated themselves to policies that inhibited those freedoms. Revisiting these difficult legacies can and should be a pivotal part of our conversations about what looms on the horizon, particularly as Canada’s most important ally, the United States, presses for a “summit of democracies” in the hopes of rallying against the rising tide of autocracy and authoritarianism (Miller 2021). How Canada navigates relations with China, for instance, will depend in large part on how the United States decides to manage its own competition with Beijing.

Such sharp distinctions, pitting democracy against authoritarianism, can easily obscure the much more messy realities of policy making in Ottawa. For the most part, Canadian governments have had a far less principled track record, favouring business as usual with authoritarian countries — with a heavy emphasis on business. Doing business with authoritarian governments remains difficult to sell to voters across the country, but it has typically been easier than bearing the economic costs of taking a principled stand.