When, in mid-September, Australia, the United Kingdom and the United States announced the new “AUKUS” security pact among the three partners, it was clear that their first priority was nuclear-powered submarines for the Royal Australian Navy.

As US Naval War College Professor Andrew S. Erickson wrote in Foreign Policy, the nuclear submarine play is a “no brainer” for Australia. Even though the deal to procure nuclear subs through technology sharing with the United States and the United Kingdom upset France, which had been set to sell conventional attack submarines to Australia, the move was a diplomatic and security master stroke for Australia, which seeks closer security integration with the United States as tensions with China continue to rise.

The power and endurance associated with nuclear submarines speak to what Australia calculates it needs for its own defence in a tough neighbourhood. China has adopted a threatening posture toward Australia, and the latter clearly feels there is no option but to respond with a show of strength.

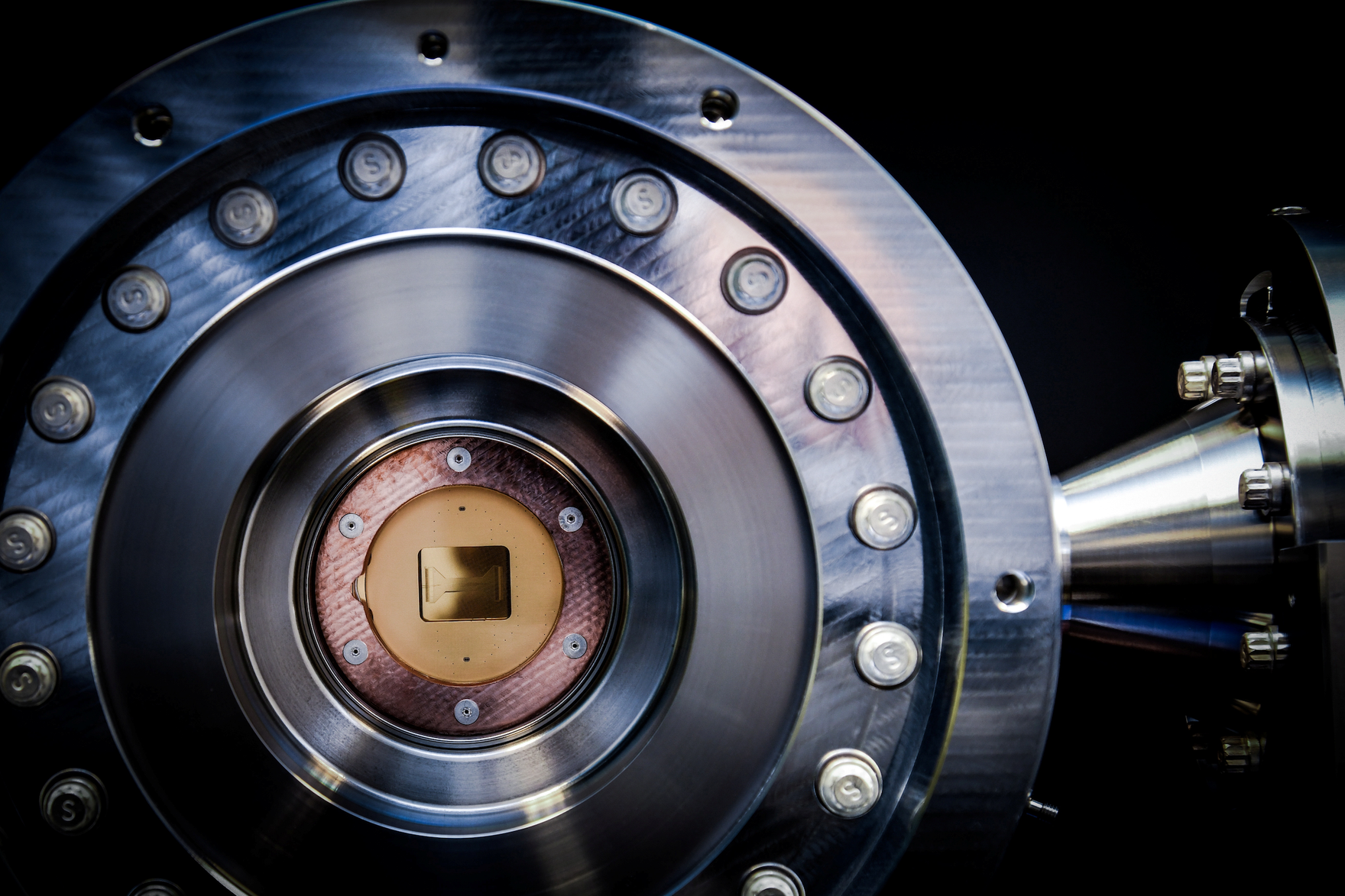

But as I wrote shortly after AUKUS was announced, this deal was never going to be limited to nuclear subs. The trio of partners telegraphed from the outset that the agreement would expand to deeper collaboration on high-tech initiatives such as cybersecurity and quantum cryptography.

Tom Tugendhat, chair of the United Kingdom’s foreign affairs committee, put his finger on it from the day the pact was announced. He wrote, “From artificial intelligence to advanced technology the US, UK and Australia will now be able to cost save by increasing platform sharing and innovation costs. Particularly for the smaller two, that’s game-changing.”

In a mere two months — no time flat, in international diplomacy — AUKUS members have brought this intention to life.

The Wall Street Journal reported on November 17 that Australia plans to invest US$81 million in quantum technology, including a new innovation hub “that will foster strategic partnerships with like-minded countries” to commercialize that forthcoming Australian research.

Indicating the depth of the technology sharing likely to underpin the new institute’s research, Australian political science professor Andrew O’Neil, quoted in the same article, has stated that the “AUKUS pact gives us access to key technologies that can reinforce our ability to maintain self reliance as a national defense strategy going forward.” O’Neil says that, historically, “there’s always been a slight point of contention among Australian policy makers in that America has never really let Australia into the crown jewels of U.S. capabilities.”

For Canada, this should put the opportunity cost of exclusion into sharp focus.

The true, long-term value of the AUKUS pact extends well beyond nuclear subs, and even beyond obtaining access to advanced US technologies: it’s about collaborating on dual-use technology development.

In developing advances such as quantum technology, the goal for Canada should be to reach the forefront of research, generate intellectual property with commercial potential, and attract investment that creates wealth and jobs, as well as increased national security. That’s exactly what Australia is doing with its new innovation hub.

Equally, being at the centre of the development of new technologies, paired with persistent global engagement, would enable Canada to help establish the technical standards associated with this new tech. Countries and industry leaders that contribute to setting standards in their areas of strength gain an advantage in scaling their companies and seizing commercial opportunities globally.

As Keith Jansa, the CEO of Canada’s leading technology standards–setting organization, the CIO Strategy Council, said to me, “Standards reflect the interests of those who participate in creating them. This is certainly not lost on the partners in AUKUS as they deepen ties to enable interoperability in cyber, AI and quantum.”

While Canada’s exclusion from AUKUS is a strategic concern, especially in terms of what it implies for this country’s strategic relevance and industrial leadership, there are signs the Government of Canada is moving in a more assertive direction on China, and in the Pacific region more broadly, possibly following the shock of being left out of — and, reportedly, not even being consulted on — the creation of AUKUS.

In recent weeks, the Royal Canadian Navy sent the HMCS Winnipeg on a freedom of navigation exercise through the Taiwan Strait, sending a clear message that Canada supports Taiwan’s continued autonomy. Canada has also begun developing a new Indo-Pacific strategy, following months of pressure from the United States.

These are positive developments. To move from checkers to chess, though, Canada needs to remain focused on the economic opportunity associated with existing and emerging defence pacts.

That would put Canadian innovators in a better position to grow while supporting this country’s national security, as well as that of our allies.