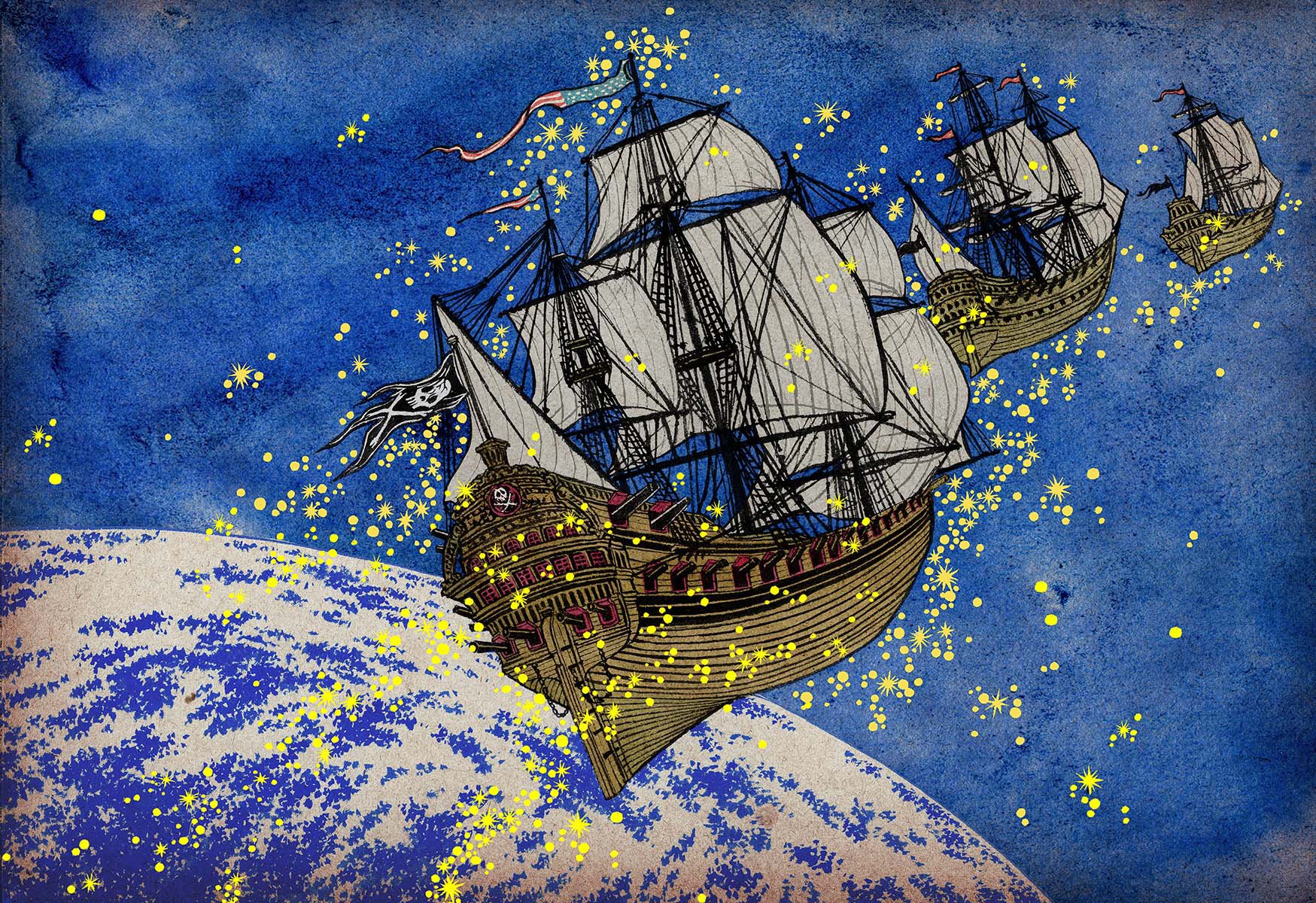

We are in the midst of a historical recurrence — a moment in which events echo a pattern from the past. With the burgeoning of the space economy and the scheduling of human-crewed missions to the Moon and Mars, the world is at a juncture similar to that experienced in the fifteenth century, during the onset of the Age of Discovery.

Indeed, there are numerous parallels between the maritime trading armadas of Spain, Portugal, France, the Dutch Republic and England and the modern-day space industrial complexes emerging in various nations. Those older armadas eventually led to the territorial colonization by Western European nations of most of Asia, Africa, Oceania and the Americas.

Today, the modern space industrial complex is poised to usher in the colonization of near-Earth space. This poses myriad challenges for global governance. There is an urgent need to amend existing international space treaties — the Outer Space Treaty, the Rescue Agreement, the Liability Convention and the Prevention of Arms Race in Outer Space, to name several. Additionally, now that the colonization of space appears imminent, policy makers must move rapidly to formulate international regulations that will preserve the common heritage of humanity. This is a matter of growing urgency.

Parallels between the Age of Discovery and the New Space Age

The maritime armadas of Western Europe in the Age of Discovery began with exploration, then pursued trade and, subsequently, colonization. Initially, these armadas served European internal conflicts in the littoral waters of the Atlantic. But eventually, with exploration, their contests played out thousands of nautical miles from their littoral waters, in the so-called New Worlds.

Indications of a historical recurrence, in the context of space exploration and exploitation, become ever more apparent with growing investments in interplanetary vessels, crewed and uncrewed, extending humanity’s reach to the Moon and Mars. A gamut of global space governance challenges will undoubtedly rise, should the leading nations or a group of nations with interplanetary armadas — Russia, China, the United States, the European Union — begin to extend their rivalries in the near-Earth space, just as occurred at sea centuries ago, around the globe.

Until the fifteenth century, so-called green-water maritime activities, those close to home, were prevalent throughout the Eastern Hemisphere, across Asia and in Southern and Western Europe. Maritime armadas supported mainly by the joint-stock companies — such as the East India Company, the Hudson’s Bay Company, the Dutch East India Company — of Western Europe accelerated the development of blue, or deep-water, navies with the support of more comprehensive financing, innovation and industrial ecosystems — many outside the immediate jurisdiction of state governments, which were then mostly monarchies. In the same vein, spacefaring nations are cultivating a vast ecosystem of private patrons for their space programs, which, from the advent of the space age in the 1960s, had been led, financed and operated mainly by governments. It therefore becomes crucial to draw parallels between the historical aftermath of joint-stock companies in the New Worlds era and the potential consequences of the new private patrons presently working toward space colonization.

The world over, nations across the political spectrum have begun to encourage private sector participation in their respective space programs. China, a known proponent of state-run enterprises, is cultivating its quasi-private space innovation and manufacturing companies to lead it into space. Chinese companies are quasi-private, as their beneficiaries and benefactors affiliate with the Chinese Communist Party and the State Council.

Two monarchies, the United Arab Emirates and Luxembourg, both new entrants in the global space economy, are cultivating the private space-innovation ecosystem with substantial investments. The United States’ incessant efforts to commercialize space and control the levers necessary to maintain its existing space superpower status are well known; unsurprisingly, some of the most famous and prolific private space companies are based in the United States. However, even in the US case, private space companies are beginning to receive support from the military-industrial complex, which has now evolved into the space-military-industrial complex.

It is possible that just as the New Worlds became battlefields for European nations, near-Earth space, too, may become a theatre of war.

There is no reason to believe that history will repeat itself exactly, or that the parallels drawn in this analysis between two time-separated enterprises will find expression in a precisely similar manner. The time it took for the exploration and the colonization of the New Worlds was brief. The Age of Discovery occurred within the realms of the planet hospitable to navigation. In the case of space flight and exploration of the solar system, the timeline will be longer. The range of economic activity in space will require significant technological, financial and human endurance; and all this will occur in the relatively inhospitable expanses of Earth’s orbit and beyond. As access to near-Earth space increases, the list of competitors in the global space enterprise is also increasing. The longer that list, and the greater the anticipated economic returns from activities in near-Earth space, the smaller the share of stakes, and the more rambunctious the push to derive short- and long-term gains.

With numerous nations achieving ever-expanding access, each pursuing its own interests, geopolitics will evolve into astropolitics. It is possible that just as the New Worlds became battlefields for European nations, near-Earth space, too, may become a theatre of war. But, since warfare is an energy-demanding activity, and generating energy for any human pursuit in space is expensive, much of the conflict in space may remain non-kinetic and hybrid — fusing electronic, cyber and electromagnetic technology amid economic, legal, informational, corporate, political and psychological warfare. Such hybrid astropolitical conflict may suit nations with a growing assemblage of space-based assets dedicated to bolstering their geopolitical security and economic interests. Indeed, astropolitical blocs are already emerging to maximize strategic returns for the major players.

Astropolitical Blocs Manifest Geopolitical Bipolarity

Astropolitical blocs are not new. The first such bloc was the Interkosmos program, formed in April 1967, the lead proponent of which, the Soviet Union, managed to draw in nearly all of the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (COMECON) members — the Eastern bloc countries, along with a number of other socialist states such as Mongolia and Vietnam — as well as non-COMECON partners such as France, the United Kingdom, Japan, Austria, Syria and India.

Central to Interkosmos were the Soviets’ capabilities in human spaceflight and their invitations to other countries to join the expeditions to the Salyut space stations. Interkosmos achieved numerous soft-power geopolitical goals for the Soviet Union, pressing its space-station diplomacy forward at a time when only two nations were capable of this, the other being the United States. The European Space Agency, founded in 1975, is a bloc of space agencies of member states; however, to date, it has not expressed concerted astropolitical ambitions.

Today, China and the United States both possess mechanisms to exert themselves as principal partners of the space blocs they are respectively assembling. The members of the US-led bloc are signatories to the Artemis Accords, while China is undertaking a two-way approach to setting its Earth-Moon Special Economic Zone. The China Manned Space Agency is pushing its space-station diplomacy in tandem with the United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs (UNOOSA) to attract nations to participate in the China Space Station (CSS). This approach implies China’s way of engaging potential non-Artemis partners to join the CSS. China is also using its Belt and Road Initiative to engage potential non-Artemis partners to join the Spatial Information Corridor, also called the Space Silk Road. As the first step in the latter approach, China is partnering with Russia — highly unlikely to join Artemis — to construct the International Lunar Research Station (ILRS). In the first few rounds of deliberations, the ILRS has attracted attention from France, Germany, Italy and the Netherlands, along with the UNOOSA. Italy’s collaboration in the CSS is noteworthy because the Italian Space Agency is a signatory on the Artemis Accords, whereas France, the Netherlands and Germany are not as yet.

Given these plans initiated by astropolitical blocs, it seems likely that the solar system will witness colonization but in a manner that circumvents the narrow interpretation of “national appropriation,” which is the core of the global commons theory proposed in the 1967 Outer Space Treaty and the largely unratified 1979 Moon Treaty.

In effect, with astropolitical blocs pursuing their space goals en masse and not as individual nations, the clauses in these treaties that prevent ownership of extraterrestrial resources by a country could be bypassed. Furthermore, no government, no matter how economically strong, would want the burden of being the sole investor; sharing risk offers a better chance of deriving profits through the entire life cycle of any enterprise.

In the past 30 years, with expanding access to outer space — sometimes referred to as the democratization of space — many nations have acquired elementary space capabilities. Some of these new entrants do not have the end-to-end technological competencies that the superpowers enjoy, but they do possess some core competencies. The United Arab Emirates’ growing reach in additive manufacturing, Luxembourg’s wherewithal in blockchain and Australia’s competence in situational awareness are examples. The participation of such adept new spacefaring nations brings immense value and thus is a desirable end for any superpower leader of the bloc to which they belong.

Although the international order is rapidly becoming multipolar, it will very likely soon revert to bipolarity, with the formation of distinct US- and China-led astropolitical blocs. Nations that have not affiliated with either of the two blocs are less likely to form a third cohort. None of them, including the highly space-capable France, Germany, India and Israel, are attempting to create a bloc, primarily because they have no obvious leader, and no apparent intent to conjoin strategic interests beneath one umbrella.

The resulting astropolitical bipolarity and ensuing tension have the potential to become severe, especially in the absence of a third, balancing cohort. Indeed, the lack of an influential third cohort reduces the chance of arbitration between the two blocs. As these blocs mature with time, a game of sanctions and counter-sanctions may evolve, in which cross-bloc partnerships could be eschewed, and total allegiance to one’s bloc be demanded.

That said, the twentieth-century “Space Race” between the United States and the Soviet Union is not an exemplar for the emerging contest between the US- and China-led astropolitical blocs. No one nation can sustain an open-ended and spiralling race for too long. Socio-economic and political costs and liabilities force governments to cut the spiral and enter a détente. But competing multinational blocs are more resilient than individual countries. Blocs can sustain a long spiralling race due to resource pooling and risk sharing. Therefore, the new space race could span a longer period than did the US-Russia Space Race, and eventually lead to either détente or a war.

Today, the scope and the nature of space colonization, no longer the province of science fiction, demand careful scrutiny. The growing role of the private sector, the expanded ambit of space exploration, the myriad space capabilities churning out of incessant research and development, and the political and geopolitical thrusts toward space colonization will test the limits of existing treaties. Many of the cutting-edge space-based activities will breach into unregulated grey areas not bound to any international consensus. All this is imminent.

The first steps of colonization are likely to be taken in the next 15 years through the scheduled and well-publicized Artemis missions or the ILRS missions. Investments made by bloc partners will freight these missions with strategic financial and technological interests. The partners’ desire to secure returns on their investments will impose new commercial space activity, from tourism to space-based manufacturing to mining. This is highly likely to lead to revision of extant space treaties and protocols. With new legal validations, space colonization will only grow in scale and scope.

The Space Economy Should Include Planetary Protection

During the COVID-19 pandemic, governments around the world have become sensitive to the importance of quarantine and physical isolation in the context of epidemiology. Like any other biological species, humans adapt to their environment.

However, along with adaptation can come exposure to foreign micro-organisms, some of them causing disease, including the infectious kind. Historically, colonization has led to new trade routes and goods, more frequent travel and the spread of disease. Indigenous peoples in North America contracted Old World diseases, such as smallpox, from Western European colonizers. In the same way, although the biological load in space is very low, frequent human travel in micro-gravity, conditions prone to radiation and extreme space environments can cause medical emergencies, trauma and chronic physiological effects.

Most space exploration and habitation plans now revolve around a few extraterrestrial sites, be it the lunar South Pole–Aitken Basin, which is rich in water ice, or Mars, with its lava tubes (natural tunnels through which lava travels beneath the surface of a lava flow) and caves. It’s possible that these regions may be home to extreme-environment micro-organisms, or extremophiles, that could be carried back to Earth (backward contamination), deliberately or otherwise, via human travellers or fomites (objects or surfaces that can passively carry infectious agents); similarly, travel from Earth to the Moon and Mars could result in forward contamination of Earthly extremophiles via travellers or fomites. It will therefore be vital that not only the two principal astropolitical blocs but also international multilateral bodies — such as the Committee on Space Research and the International Space Exploration Coordination Group — exert greater deliberation on planetary protection. Their task will be, first, to prevent any such contamination and, second, to reduce the risk of such contamination turning into an epidemic or pandemic on Earth.

Besides infectious micro-organisms, biological molecules known as prions pose another grave threat. Prions are flexible strands of proteins that can flexibly fold due to external factors. They are adaptive and can mutate on every refolding, leading to a unique disease after each fold or mutation. Such strands lack nucleic acids — deoxyribonucleic acids (DNA) or ribonucleic acids (RNA) — but are capable of Darwinian evolution and interspecies transmission. A forward-carried prion can mutate and refold in space environments to become a hazardous, disease-inducing agent. If there are strands of proteins present on the Moon, asteroids or Mars, they could, through access to a large number of human, plant or animal hosts — which space colonization could provide — mutate into disease-inducing forms. Therefore, space colonization requires careful preparedness and situational awareness. Neglecting to ensure the fidelity of planetary protection protocols could lead to precarious biological surprises and “black swan” (unprecedented) events. Prion-driven threats would almost certainly not be limited to human diseases but also bring a host of unpredictable harms to other plant and animal life on Earth.

Promoting Democratization in Near-Earth Space

Another primary concern regarding space colonization is ideological polarization. Formed due to political commonality among like-minded members, astropolitical blocs will be prone to ideological blindness and biases. The bloc leaders could deliberately or otherwise model the architecture, operations, financing and sustenance of the colonization on the basis of their characteristic dogmas. It is to be hoped that such inclinations will not be as culturally ruinous as territorial colonization has been on Earth.

To be sure, extraterrestrial sites do not have Indigenous cultures and civilizations. The problem remains that territorial colonization occurred amid the relative comforts of Earth, whereas space will remain inherently hostile to human life. Since every payload — equipment or human — would be indispensable to the operation of the settlement or colony, the concept of surplus will not exist. Sparing and judicious use of resources will be essential.

Bloc-led colonization will also likely raise the question of inclusive representation of earthly cultures and societies. Some cultures and societies may be part of the blocs but have less control over the narrative than those leading the blocs. Leaders may attempt to assert their preferred cultures, ethics and etiquettes and may not provide space for equal representation of member nations. Some may not be part of any bloc and consequently may have no stake or voice in this historic enterprise of humanity.

When stakeholders of space enterprises express the desire for humanity to become a multiplanetary species, equal opportunities for all cultures, societies and cohorts rarely draw mention. After centuries of territorial colonization, many Indigenous and colonially suppressed communities are finally obtaining a voice on subnational, national and international platforms. The continuing spaceward progress of such communities requires access: to tertiary technical education; to the ability to preserve their Indigenous ethos, beliefs and social practices; and to channels to share opinions.

Given a bloc-led colonization of space, in which the focus is primarily on strategic and economic returns, the blocs will need to create opportunities for broad and varied socio-cultural input. Many communities around the globe retain rich cultural practices from the non-globalized times before colonization. People with this cultural memory, moored in a resourceful and minimalist way of life, will be of great help and importance to any bloc in developing sustainable extraterrestrial colonies.

There is a danger that with space colonization, the mistakes of the territorial colonization of Asia, Oceania, Africa and the Americas could be repeated. More significant analysis is needed to identify potential areas of similarities and divergences. Such research is necessary so that historical mistakes are not repeated and to ensure that humanity’s march into space is carried out with elaborate and vigilant scrutiny. The term colonization elicits strong negative sentiments worldwide. That’s likely why alternative terms such as habitats, settlements and bases are often used to describe the future human occupation of extraterrestrial lands.

The formation of the US- and China-led blocs may successfully land humans on the Moon and Mars by the second half of the twenty-second century. But to make this human progress justifiable, we must critically examine the moral, legal and political challenges of this pending colonization. That is the path most likely to prevent future astropolitical armadas from coming into conflict.