Even as the community of nations on Earth fractures further into rival blocs, an effort to build greater cohesion in space is gathering momentum. The extent to which this succeeds, or not, may set the course of global peace and security for the foreseeable future.

Diplomats along with military, industry, civil society and academic experts are gathering in Geneva this week for the annual Outer Space Security Conference hosted by the United Nations Institute for Disarmament Research (UNIDIR). Driving the agenda: how to build cooperation across the international community as it works for the prevention of an arms race in outer space (PAROS).

The timing of the meeting is critical. Diplomatic efforts on PAROS have been on a rocket to nowhere for the past four decades, buffeted by competing aims. Some states want to ban weapons in space through a new legal agreement; others are focused on anti-satellite capabilities that target space systems, and see a need to nurture transparency and norms of behaviour to support existing laws and prevent conflict.

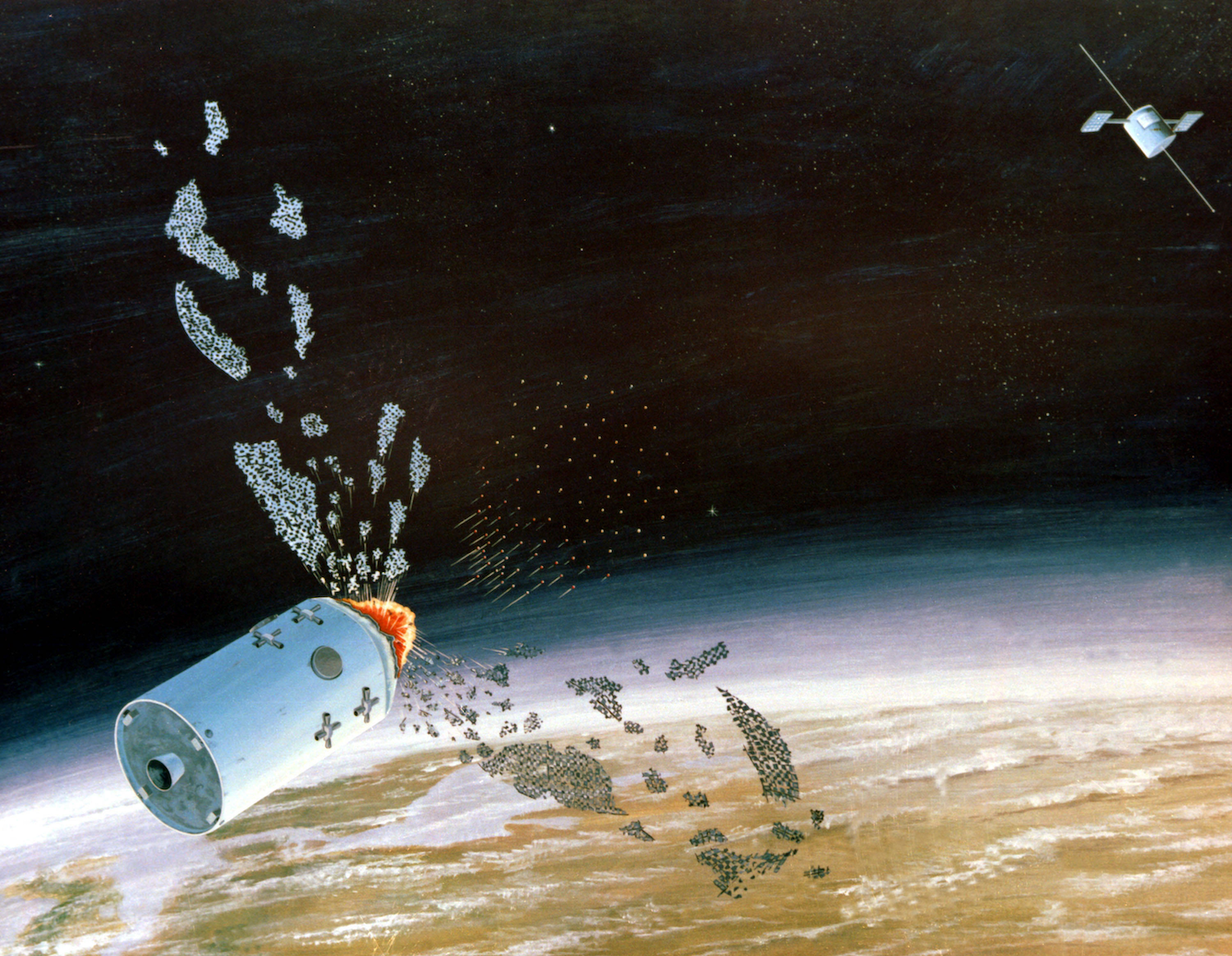

As diplomacy has faltered, threats have risen. A report from Secure World Foundation, Global Counterspace Capabilities, shows more countries developing technologies to harm or disrupt space systems. Trust in commitments to existing arms control measures is faltering. Outer space security was discussed at the UN Security Council for the first time ever this year in the wake of not one but two (failed) resolutions. These were initially prompted by concerns about potential development of nuclear weapons capabilities in orbit, which would violate one of the few existing international legal restrictions on the use of space.

Efforts to repair this dangerous situation are also at risk. Two parallel UN open-ended working group (OEWG) processes on PAROS are set to begin: one that would continue work on reducing space threats through a focus on norms of responsible behaviour, and another that would continue the work on elements of a legal agreement focused on barring weapons and the use of force in outer space.

Neither effort can succeed without the other. But attempts to build consensus on both topics have previously failed. And there is a risk that parallel efforts split participation among the international community and bifurcate the governance regime for space by adopting different approaches to law, definitions, concepts and obligations.

But there is a glimmer of hope, too. A recent diplomatic victory charts a cautious path to success. In August, a UN Group of Governmental Experts (GGE) on Further Practical Measures for PAROS adopted a consensus report outlining the scope of discussions and the varying views among states. In the field of outer space, where the extraordinary happens daily, this achievement may seem insignificant. But the content of the report offers threads of commonality across the two long-competing approaches to space governance.

The UNIDIR conference will strive to knit these threads together, building on key areas of work identified in the GGE report and tackling thorny obstacles to progress. Of importance is a diplomatic panel including the chair of the recently concluded GGE, Egypt’s Ambassador Bassem Hassan. Intended to take stock of the various diplomatic processes on space security that have been attempted in the past, the discussion provides an opportunity to reflect on how both the successes and the missteps of previous efforts can help to support progress at the two upcoming OEWGs.

A comprehensive approach to space security will require common understandings. The conference thus will lead with a consideration of the many threats and risks to space security, from the use of counterspace capabilities to natural hazards, and grey-zone activities that fall in between. A planned discussion on the existing governance framework is intended to flesh out the “dos and don’ts” of space that must inform any effort at additional rules, and to shed light on a core but illusive concept that informs the development of both norms and legal restrictions: the threshold of the use of force.

But more needs to be done. Also needed are synergies across the various pieces and actors of the outer space governance regime. Here, a focus on the links between space security and space safety is critical, not least to address one of the most pernicious obstacles to arms control: the dual nature of space technology, which can often support both military and civilian or commercial aims, and both helpful and harmful applications.

Finally, neither the pursuit of legal agreements nor norms of behaviour can bring success in the absence of verification and other measures to nurture confidence in their implementation. Expert input on the range of tools available to support transparency and confidence as well as technical verification is urgently needed.

If astronauts are the “envoys” of humankind, diplomats must be the “astronauts” of peace and security in space, daring to go where none have gone before. The UNIDIR conference will help to give them the tools to get there.

This piece first appeared in Space News.