While Chinese computational propaganda has in the past consisted largely of effusive praise for the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), that has been changing. Since the CCP began embedding its treatment of China’s Uighur Muslim minority population into counterterrorism rationales in the early 2000s, the Chinese state has become more aggressive and markedly negative in its propaganda.

Recent diplomatic escalations about the alleged targeting of Canadian member of Parliament Michael Chong and his family in Hong Kong have heightened concerns about Beijing’s intolerance for international criticism — especially on matters it considers as integral to national security, such as the treatment of the Uighurs in Xinjiang, an autonomous territory home to many ethnic minority groups. The Uighurs account for 45 percent of the region’s population but less than one percent of China’s total population.

The Uighurs, a people indigenous to the vast region of Xinjiang, live predominantly in Western China, with significant diasporic communities in Central Asia. Their culture and Islamic traditions are unfamiliar to most of the country’s Han Chinese majority. With the collapse of the Soviet Union, Xinjiang’s neighbouring regions, such as Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan, became independent. That revived nationalist ambitions among the Uighurs in Xinjiang and led to local protests. These signs of a simmering separatism have persisted, marked by scattered outbreaks of violence. Increasingly, the Chinese state has come to view Uighurs as not only suspiciously different but also dangerously seditious. Authorities accuse the largely Muslim minority of separatism and terrorism.

Since the early 2000s, the Uighurs have been targeted by Beijing with various assimilative policies, which place restrictions on cultural and religious practices such as dress, Islamic grooming, use of their own language and adherence to Islamic dietary laws. Many Uighurs have even been detained in so-called re-education centres. The UN High Commissioner for Human Rights asserted last year that while the number of detainees is unknown, it is likely to be “very significant, comprising a substantial proportion of the Uyghur and other predominantly Muslim minority populations.”

What Role Does Propaganda Play?

At the Propaganda Research Lab at the Center for Media Engagement at The University of Texas at Austin, we study computational propaganda — how social media and other digital tools are used to manipulate public opinion and spread disinformation — and we’ve observed a marked shift in the tenor of this propaganda.

Both propaganda and public diplomacy are essential components of Chinese soft power. Indeed, they are considered by Beijing to be crucial to not only regime survival but also China’s international success. From the CCP’s standpoint, protecting China’s national interests means employing and continuously developing new communication capabilities to support Chinese state messaging internationally, while strengthening national cohesion domestically.

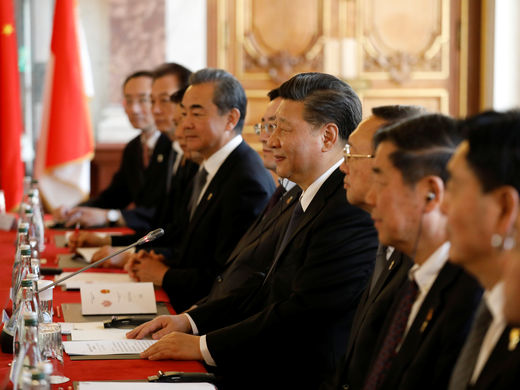

The CCP has coordinated online activities domestically (mostly on Weibo, one of the biggest social media platforms in China) and internationally (mostly on Twitter). China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs is central to this effort. It holds its own accounts and also leads individual diplomatic accounts that convey congruent messages. This coordination ensures that content adheres to Beijing’s chosen political direction and values, such as promoting ethnic harmony under CCP rule.

Beyond that, the CCP’s international propaganda work is multi-faceted and includes purchasing news outlets, occupying space in foreign mainstream media (usually by buying columns), growing its domestic media networks, and working social media. On Twitter, China has employed automated computational propaganda — including tweets written about the Uighurs in Xinjiang and the coordinated dissemination of these posts, which our research analyzed.

The Uighurs in Xinjang present a twofold challenge for the Chinese state: First, their faith separates them from the 90 percent of citizens who are Han Chinese. Although China is officially atheist, many Chinese adhere to Buddhism or Taoism. Especially since the ethnic riots in 2009, the practice of Islam has been interpreted by Chinese authorities as a threat to the state’s Communist ideology, which rests on a vision of communal identity. Second, acts of repression in Xinjiang by state authorities have attracted international, in particular, Western, condemnation. That can hurt China’s reputation internationally, and thus its ability to project soft power.

Chinese Propaganda as Part of Geopolitics

However, social media companies regularly detect propaganda campaigns — and Twitter, in particular, had developed able internal research capabilities to identify and remove manipulative accounts that boosted specific messages inauthentically (this refers to Twitter before its takeover by Elon Musk).

Regarding a specific campaign removed by Twitter in December 2021 (because of the amplification of CCP narratives related to the treatment of the Uighurs), researchers at the Propaganda Research Lab found that 2,048 accounts spread significant quantities of negative messaging between March 2019 and March 2021, often accusing Western countries of lying and of hostility toward Chinese people.

Foreign interference, attempts at intimidation, and the subsequent tit-for-tat expulsion of diplomats, as in the Michael Chong case, grab headlines and are telling signs of worsening relations between China and the West.

But Canada and other Western nations interested in preserving a liberal global order need to pay attention, not just to the highest-profile cases but to greater Chinese assertiveness overall — including in its propaganda. Should the CCP continue to invest in international propaganda while global social media companies cut back on staff, the liberal world order is likely to suffer further erosion.