Key Points

- A good patent regime achieves the right balance between the need to incentivize innovation and the need for public access.

- The simplest model proposes that while patents are necessary to foster innovation, they generate deadweight losses (DWL) for the economy. The optimal patent term achieves the best trade-off between these effects.

- Patents are not the only way to incentivize innovation, nor are they necessary for innovation to take place in most cases.

he patent regime must be a central consideration of any modern innovation strategy. Patent rights influence, among other things, firms’ incentives to innovate, knowledge diffusion, market organization, public access to technology, exports and foreign direct investment. They can either promote or inhibit innovation, depending on the strength of the patent rights and the specifics of the regime.

There are two principal and diametrically opposite moral philosophies on patent rights. First, the "natural rights view" sees an innovation as naturally belonging to its creator, the party that had the inspiration and invested in its development. Under this view, any action other than assigning full rights to the inventor constitutes theft. The opposite philosophy, the "public rights view," is that knowledge and ideas belong in the public domain, for all to discuss, use and build on, and that the assignation of private property rights constitutes an improper restriction on the rights of the public. This view is grounded in the fact that the laws of nature that govern our world exist separately from humans, and that just because an individual was first to discover something should not mean that the individual gains ownership over it. Between these extreme positions is room for a system that both recognizes some rights for inventors and affirms that information and ideas fundamentally belong to all. Thus, the approach that most legal systems have adopted in practice is a utilitarian one, where the need to incentivize innovation is traded off against the need for public access. Such a utilitarian approach is doubly important because of innovation’s central role in driving improvement in our standard of living.

There are two principal and diametrically opposite moral philosophies on patent rights.

Patent rights can promote innovation in three main ways. First, they can facilitate knowledge diffusion because, as a condition of receiving a patent, inventors are required to describe the technology in sufficient detail so that someone skilled in the art can reproduce it. This requirement is long-standing. The first US patent act, passed by Congress in 1790, stipulated that a patent should “enable a workman or other person skilled in the art…to make, construct or use the same.”1 However, while facilitating diffusion may be a principal objective of patents, it does not seem to be an important mechanism in practice. Firms and their patent lawyers often obfuscate the workings of a technology in the patent’s description, and patent examiners rarely effectively enforce the full disclosure requirement. Furthermore, managers in major technology companies routinely instruct their engineers not to search the prior art in a given technological field to mitigate the risk of a willful infringement court ruling and its associated larger damages (Boldrin and Levine 2013). Surveys of inventors, such as a report by Industry, Science and Technology Canada (1989), have confirmed that high-tech firms do not consider patents to be a particularly useful source of new information.

The second way in which patent rights can promote innovation is by creating a market for ideas and innovation, thus facilitating transactions such as the licensing or sale of an innovation and enabling the efficient allocation of ideas and technology. Creative firms could focus on the development of technologies and allow other firms with comparatively better production, distribution or marketing capabilities to undertake the commercialization (Arrow 1962; Arora 1995; Gans and Stern 2003; Federal Trade Commission 2011). The extent to which patents foster innovation through this mechanism, while likely not negligible, remains an open question.

Third, and most importantly, they can increase the incentives for private agents to innovate by providing a higher return to innovation. This being the principal mechanism, it is examined in detail below.

Simple Model of Patents and Private Incentives to Innovate

Understanding why patents could be necessary to foster innovation by private agents begins with the recognition that knowledge is non-rivalrous. That is, the use of a given piece of knowledge by one party does not preclude another party from also using that same knowledge. Put differently, once the cost of developing knowledge has been incurred (perhaps by running experiments to discover the laws of nature or repeated trials to discover how to make a technology work), there is zero additional cost to having more parties use that knowledge. What’s more, knowledge is largely non-excludable. Once created, it is difficult to keep others from learning about and using the knowledge. This non-rivalrous, non-excludable nature of knowledge makes it a public good that can drive large increases in welfare. But, paradoxically, for the same reasons that it is so valuable to the public, knowledge can be underprovided by the market, or even not provided at all.

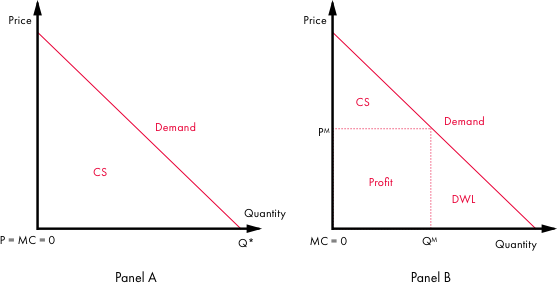

The fundamental problem is that when an innovation can be quickly imitated by others, any profit generated by the innovation is quickly eroded. Figure 1, Panel A, shows the market for a product that is the result of an innovation. If the marginal cost of providing one additional unit of the knowledge good is zero, and the good is non-excludable so that there is imitation, competition will ensure that the equilibrium price is zero. This equilibrium is good for consumers because all consumers who value the good receive it, and they get it for free. However, because there are no profits to be had for the original innovator, the innovator would optimally choose not to invest in the development of his or her idea in the first place.

The solution to this problem is to make innovations excludable. This is done in practice by granting and enforcing patents that cover such innovations. Because inventors now possess a monopoly on the use of the innovation, they will choose to sell the knowledge good at the price PM and make profit PMQM (the square labelled “Profit” in Panel B). To the extent that these monopoly rents cover their development costs, the inventor will undertake the development of their idea. Of course, giving inventors patent rights comes at a cost. In the new equilibrium, consumers must now pay to consume the knowledge good and are thus worse off. For consumers who still choose to consume the good, there is no adverse impact to overall welfare because the higher price simply results in a transfer from consumers to the innovator. However, consumers who value the knowledge good at less than the monopoly price will choose not to consume the good, which leads to DWL for the economy and a lower welfare.

In summary, the simple model suggests that without patents there will be no innovation by private agents and the entire welfare associated with an innovation will be lost. With patents, innovators will mark up the price of their innovation, which results in not everyone accessing the innovation and thus lower welfare.

Figure 1: Market Equilibrium without Patents (Panel A) and with Patents (Panel B)

Optimal Patent Length

The primary drawback of patents, the associated DWL, can be limited by making a patent’s monopoly temporary. The trade-off is that limiting the term of patents weakens the incentives of inventors and that certain innovations, which from the point of view of social welfare should be undertaken, won’t be. Conversely, lengthening the term of patents will increase DWL on all innovations, including those that would have been undertaken even with the shorter patent term. As a result, the optimal term is a function of the distribution of ideas that could be developed into innovations.

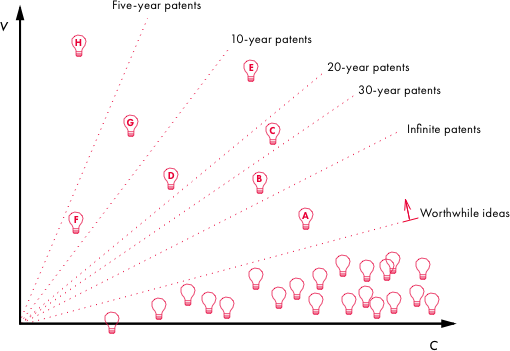

As Figure 2 shows, some ideas are better than others in that they may cost less (C) to develop into a useful innovation, or because the innovation may generate more value (V). Some ideas (for example, H) are very good in that they cost little and generate a lot of value. From the point of view of maximizing society’s welfare, all innovations that generate (net present) values greater than their costs should be developed (at least in the absence of DWL). In the figure, these innovations fall above the “Worthwhile ideas” line (all the ones labelled with a letter). However, because patents decentralize the decision of whether to pursue an innovation, not all of these ideas are going to be developed. In fact, even if patents are infinite, idea A won’t be developed because its cost will exceed the inventor’s discounted stream of monopoly profits (as was shown in Figure 1, Panel B, even with a monopoly the inventor can only capture part of the value of the innovation). If patents are given a 20-year term, the net present value of an inventor’s profit stream is further lowered, so that now ideas B and C, too, will not be developed. If the patent term is futher reduced to five years, only idea H will be developed.

The figure illustrates the basic trade-off between increasing the incentives of inventors so that more ideas are developed (by increasing the term) and decreasing the DWL associated with innovations that would have been developed regardless (by decreasing the term). In the figure, the optimality of a 10-year or 20-year term depends on whether the welfare gains generated by innovations D and E outweigh the larger welfare losses associated with a longer term on innovations F, G and H. It is therefore impossible to determine the optimal patent term unless one has perfect information on the cost and value of every idea. But the figure illustrates that as the term lengthens, each subsequent increase is likely to generate fewer and fewer additional innovations (the cone between the 10- and 20-year patent lines is larger than the cone between the 20- and 30-year patent lines).2 Moreover, each subsequent increase of term raises the DWL on a larger number of patents. Therefore, one can expect significant welfare costs from increasing the patent term too much.

Figure 2: Trade-off between Shorter and Longer Patent Terms

Are Patents Really Necessary?

Importantly, the simple model assumes that innovations can be imitated quickly and at zero cost. In practice, it may take time for potential competitors to learn of the new innovation, let alone imitate it. This could give the original innovator a first-mover advantage that, even in the absence of patent rights, provides sufficient incentives for the inventor to develop his or her idea. Alternatively, if imitation costs are non-zero, the result would be limited entry, a positive equilibrium price and, potentially, sufficient profits for the inventor to cover development costs. Irrespective of the speed and cost of imitation, some markets may also have significant regulatory or other barriers to entry that limit competition and, thus, provide a profit for the innovator. Therefore, it may well be that, in practice, most innovation would occur even without the additional incentives of patents.

Patents are also not the only way to incentivize innovation. While patents have the advantage that they fully decentralize decision making and governments need not have knowledge of innovation opportunities or the value of innovations, and that under a patents regime the costs of development are ultimately borne by the innovation’s users and not by the public, patents are in general less efficient in terms of overall welfare than many alternative mechanisms to incentivize innovation.

Irrespective of the speed and cost of imitation, some markets may also have significant regulatory or other barriers to entry that limit competition and, thus, provide a profit for the innovator.

One alternative to patents, and a first-best from a welfare perspective, is for a sponsoring agency or government to offer the inventor a prize for producing the innovation. If the size of the prize is equal to the consumer surplus in Figure 1, Panel A, the prize has the added benefit that the inventor will choose to develop his or her idea into an innovation when it is socially optimal to do so (that is, when the cost of developing the innovation is less than the value that it generates) and will choose not to develop it otherwise. An additional benefit of this approach is that it can incentivize basic innovation and not just the applied variety, such as patents. Prizes are already being used effectively by groups such as the XPRIZE Foundation to spur innovation. And based on figures compiled by Dean Baker (2005), prizes or direct funding of research and development (R&D) could be more effective than patents to spur pharmaceutical innovation. Baker notes that, in 2005, the United States spent US$210 billion on prescription drugs and estimates that the cost would have been closer to US$50 billion in the absence of patents. And this additional US$160 billion expenditure generated, at most, US$25 billion of R&D spending (the total R&D spending of the US pharmaceutical industry in 2005).

In addition to prizes and direct funding of R&D, numerous related mechanisms for incentivizing innovation have been proposed, including buying out patents either through direct negotiation with the innovators3 or by determining the value of an innovation through a (shadow) auction of the innovation (Kremer 1998).

Conclusion

The model presented here makes the case that patents trade off DWL for increased innovation, and that there is an optimal patent term that achieves the best trade-off between them. However, patents are not the only way to incentivize innovation, nor are they necessary to obtain innovation in most practical cases. As a simplified model, it ignores the reality that innovation is cumulative and that firms respond not just to domestic intellectual property rights but also to the regimes in foreign countries. As another essay in this series will examine, in these more realistic scenarios, not only may patents not promote innovation, but they could even stifle it.