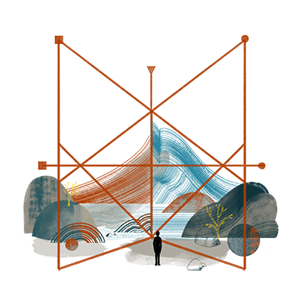

In a famous Greek parable (Marchant 1923, book 2, chapter 1), Hercules finds himself at a crossing between two paths. At the crossroads, he is visited by the female personifications of Vice and Virtue. He is told that he must choose between, on the one hand, a pleasant and easy life and, on the other hand, a severe but glorious life.

Like the young Hercules, antitrust policy today is at a crossroads. There is, however, some confusion on what Vice and Virtue represent in this context and how they will play out. Policy makers in the United States are confronted with choices that will significantly condition the future of antitrust enforcement and digital platform markets for decades to come, yet the stakes of these choices remain under-theorized. This essay identifies some “real” choices antitrust policy makers are facing. The author argues that despite the emphasis placed on labels such as Chicago School1 and Neo-Brandeisian2 (or progressive) antitrust, efficiency, consumer welfare or “bigness,” the key choice is between continuity with a past of regulatory deference and separation of markets from societal needs on the one hand, or embracing antitrust’s role in making the economy more responsive to societal needs on the other. Framing disagreements in binary terms, as disagreements between schools or camps, risks obscuring the real opportunity offered by this moment: the opportunity to reinvent what markets are and will mean in the twenty-first century.

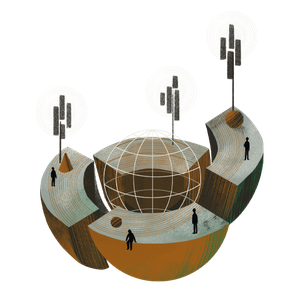

Current antitrust institutions are tentatively moving beyond the Chicago focus on prices and the consumer welfare standard. Yet the goal of maintaining or promoting competitive markets — markets over which consumers and entrepreneurs, not political subjects, are the ultimate sovereigns — remains entrenched even among Neo-Brandeisian reformers. Beyond promoting decentralized competitive markets and fighting bigness, a post-neoliberal approach should highlight the fact that antitrust and antimonopoly are politically contingent and part of a much richer suite of policy practices that together contribute to pre-structuring and restructuring marketplaces and social and political life. Moving beyond current binary disagreements in antitrust therefore requires a deliberate (re)construction of regulatory institutions and markets co-extensive with political life. Seeing antitrust through a political economy lens allows us to situate the current Neo-Brandeisian revival as part of a wider conceptual shift that questions the function and structure of digital and non-digital markets in a democracy.

A Perceived Antitrust Dilemma: Vice or Virtue

Antitrust’s current state is often depicted as that of a binary dilemma between a Chicago School and a progressive approach. It is viewed as a crossroads between a virtuous scientific approach and a vicious political one, or between a vicious efficiency-based approach and a virtuous structure-based one. The history of antitrust law is also frequently depicted through one of these lenses. Yet both neoclassical economics and neo-progressive reform bear their mark on antitrust’s hybrid history.

Antitrust emerged in the 1890s, a period marked by the advent of railroads, electricity and large conglomerates of industrial power. It took some time for antitrust law to be enforced. Despite the Sherman Antitrust Act,3 passed in 1890, more than 2,000 firms continued to merge between 1890 and 1904, leading to the creation of 157 corporations (Wu 2018, 12). In 1911, in the landmark case of Standard Oil,4 the Supreme Court finally broke the oil monopoly into 37 segments. A few years later, Louis Brandeis, US President Woodrow Wilson’s economic adviser, provided the impetus for a new progressive era of “regulated competition.” He contributed to the creation of the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) and new antitrust violations under the Clayton and Federal Trade Commission Acts5 of 1914.

Some ambitious antitrust bills have made their way into Congress and might, if successful, strengthen US institutions’ ability to address digital platform monopolies.

Despite progressive roots and early synergies of antitrust with public utilities, public corporations and other trade regulation (Novak 2020), things changed around the 1970s as part of a strong deregulatory wave. In the late 1970s, enforcement changed. The number of private antitrust cases and enforcement actions declined6 quite dramatically (Stucke 2011). Following the influence of Robert Bork,7 the Chicago School of Economics and the Harvard School of antitrust, the dominant approach to antitrust is still today economics-driven and formalistic, more focused on pursuing procedures and a consumer welfare standard that favours low prices and productive efficiencies than concerned with monopolization, market structure or vertical exercises of market power.

It is only very recently that the mood in antitrust circles has recovered an interest in early twentieth-century progressive motivations and rationales. The Neo-Brandeisian movement, shepherded by thinkers and activists including Lina Khan, Timothy Wu and Zephyr Teachout, has revived antitrust enforcement against big tech companies. All Democratic primary candidates included antitrust reform as part of their 2020 campaigns. President Joe Biden nominated a number of Neo-Brandeisians to positions of power, including Khan as chair of the FTC (McCabe and Kang 2021). Some ambitious antitrust bills have made their way into Congress and might, if successful, strengthen US institutions’ ability to address digital platform monopolies (Feiner 2021). President Biden also issued an executive order to further empower the FTC (The White House 2021).

Looking back, the story of the evolution to the present moment tends to be told in one of two primary ways: either from a neoclassical perspective, as a story of consumer welfare coupled with progressive mistakes rectified and now being repeated; or from a progressive perspective, as a natural return toward early progressive roots of fairness and antimonopoly enforcement. Adopting one of these narratives can clarify some aspects of current antitrust debates but risks confusing other aspects.

The Real Choices Antitrust Regulators Face

No matter how we look at the decisions facing antitrust policy makers, we are likely to impose our Herculean Vice versus Virtue binaries and obscure the larger picture. The agonism between Chicago School antitrust on one side and Neo-Brandeisianism on the other has produced a panoply of simplifications. Many unsolved questions in antitrust law do not admit neat binary answers. The choice facing regulators is thus not simply whether to continue to follow the consumer welfare standard or move toward a method more similar to that adopted by European regulators. The task is instead to define the normative values that antitrust enforcement should pursue and a political agenda that includes collective sovereignty over (digital) economies. The goal of this essay is to situate current debates in this broader context, both to demystify existing dichotomies and to complicate them.

Demystification

The consumer welfare standard is frequently depicted as a conservative standard. Overall, it is true that by delegating antitrust questions to economic consultants and experts, courts’ stance has grown increasingly conservative and pro-big business (Dayen 2018). Yet the consumer welfare standard does not systematically mandate conservative outcomes. Promoting business models that charge low prices to consumers can be, and has long been understood as, a progressive (Crane 2019), pro-competitive approach (Philippon 2019) to market regulation. Markets have long been seen as egalitarian vehicles for resource allocation (Anderson 2017) . What has changed during the current era is that markets now serve the political agenda of an elite, not the interests of the general public, while being represented as natural and democratizing tools.

At the same time, a Neo-Brandeisian or structuralist approach does not always have progressive implications. It was evident during Khan’s confirmation hearing that Republican support for Neo-Brandeisian reform is subject to such efforts’ ability to preserve and maintain functioning, minimally regulated and competitive markets that allow consumers to purchase an ever-expanding variety and quantity of goods and services. Breaking up large monopolies, for example, could still fuel an extractive and consumerist, albeit slightly more decentralized, economy. If too focused on maintaining or promoting decentralized marketplaces and individual consumer and entrepreneurial choices in political voids, Neo-Brandeisianism could, like its Chicago School predecessor, also fail to advance the interests of persons in the digital economy.

The first FTC antitrust complaint against Facebook,8 for example, requested a breakup remedy but defined harm to consumers in terms of individual choice on a pre-existing platform marketplace: the inability to make choices regarding “the amount and nature of advertising, and the availability, quality, and variety of data protection privacy options for users.”9 This focus on individual choice and on commercial options, which fails to directly confront the pathologies of digital platform ad-based monetization, illustrates that the departure from Chicago School neoliberalism (Mirowski and Plehwe 2015) will require many more years of experimentation and work. Neo-Brandeisian antitrust is therefore itself at a crossroads — one between continuity with neoliberalism and radical discontinuity.

Complicating Antitrust’s Future

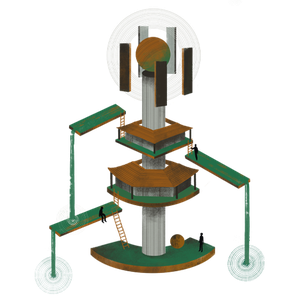

The binary choice between Chicago School antitrust and Neo-Brandeisianism, between consumer welfare and market structure, is a simplification of the past as well as a limit on future possibilities. The real choice regulators are facing is between reformism and radical change, between continuing to envision markets as apolitical, neoliberal, self-regulating spaces (Bietti, forthcoming 2022) separate from the realm of politics, or instead recognizing that they are inherent parts of society (Harris, Kapczynski and Zatz 2021) and redesigning antitrust enforcement and institutions accordingly.

The shape of markets is a contingent political and collective choice (Kapczynski, Grewal and Britton-Purdy 2021). Recognizing that markets and political life are on a continuum and are not separable spheres requires more than moving away from the consumer welfare standard or bolder regulation of monopolies and mergers. It requires a deeper shift in the perception of markets and how market regulation, including antitrust institutions, operates as part of a broader democratic framework. It requires seeing antitrust as a way to move toward more collective empowerment in areas of life currently dominated by a few private entities, such as tech giants. Antitrust conceived in that way requires radical reimagination, a mindset that hardly finds its place by framing disagreements in binary terms as between two antithetic camps.

The real crossroads antitrust faces is not the one we tend to see: one of obvious substantive and ideological conflict. The primary battle is instead about institutional and democratic reconstruction: choosing regulatory frameworks that enable collective sovereignty over productive processes and avoid shielding production from democratic rule.