In terms of geography and natural resources, Canada’s place in the world is arguably second to none. We are a significant economy (eighth largest in 2022) and consistently rank among the top countries in aggregated measures for health, knowledge and living standards. Infrastructure and technology are good. Canadian institutions are strong despite stresses made clear by the COVID-19 pandemic. Yet the future is full of challenges.

Globalization looks set to continue to shrink and disrupt the world whether we like it or not. The planet’s ecological, economic and social systems are transforming rapidly through the large, blunt footprint of human activity, interconnected markets and the relatively seamless flow of people and ideas. Critically, the digital revolution has spawned a new economy driven increasingly by intangibles and data. Institutions and governance have not kept pace with change.

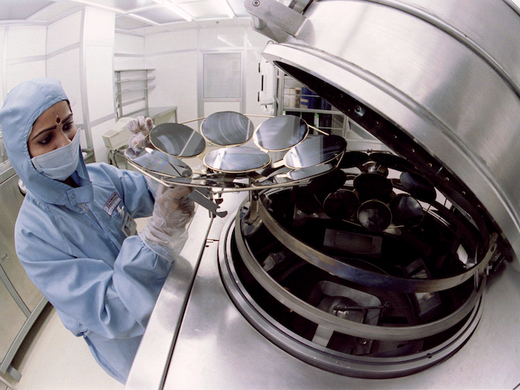

As in the fable of the small lily pads that double in number every day until they suddenly cover the entire pond, the digital age has seen exponential change made common. Consistently cheaper computing power (Moore’s law) allows companies to scale information and data in unprecedented ways and grow. Companies with data-fuelled products, such as Google and TikTok, have grown exponentially in size. Suddenly, they cover much of the “pond” and are much larger than many utilities or banks that have been around for generations. Humans are not accustomed to exponential change. But we must now seek to understand it.

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, the global economic paradigm had weakened through regular financial crises, cracks in free trade, gaping wealth and social inequalities, and the rise of populist reactions worldwide. The pandemic and its ripple effects have now pushed the neo-liberal economic model over the precipice, at a time of high debt, alarming inflation and a spike in interest rates. The tragic war in Ukraine has spurred global rivalries and buried issues of shared interest, creating risks of ongoing or even broadened conflict.

There is no consensus or apparent model to drive international cooperation, creating an increasingly fragmented system. As a result, international cooperation risks falling short of what is needed, even on issues of clear common interest such as global financial stability and climate change.

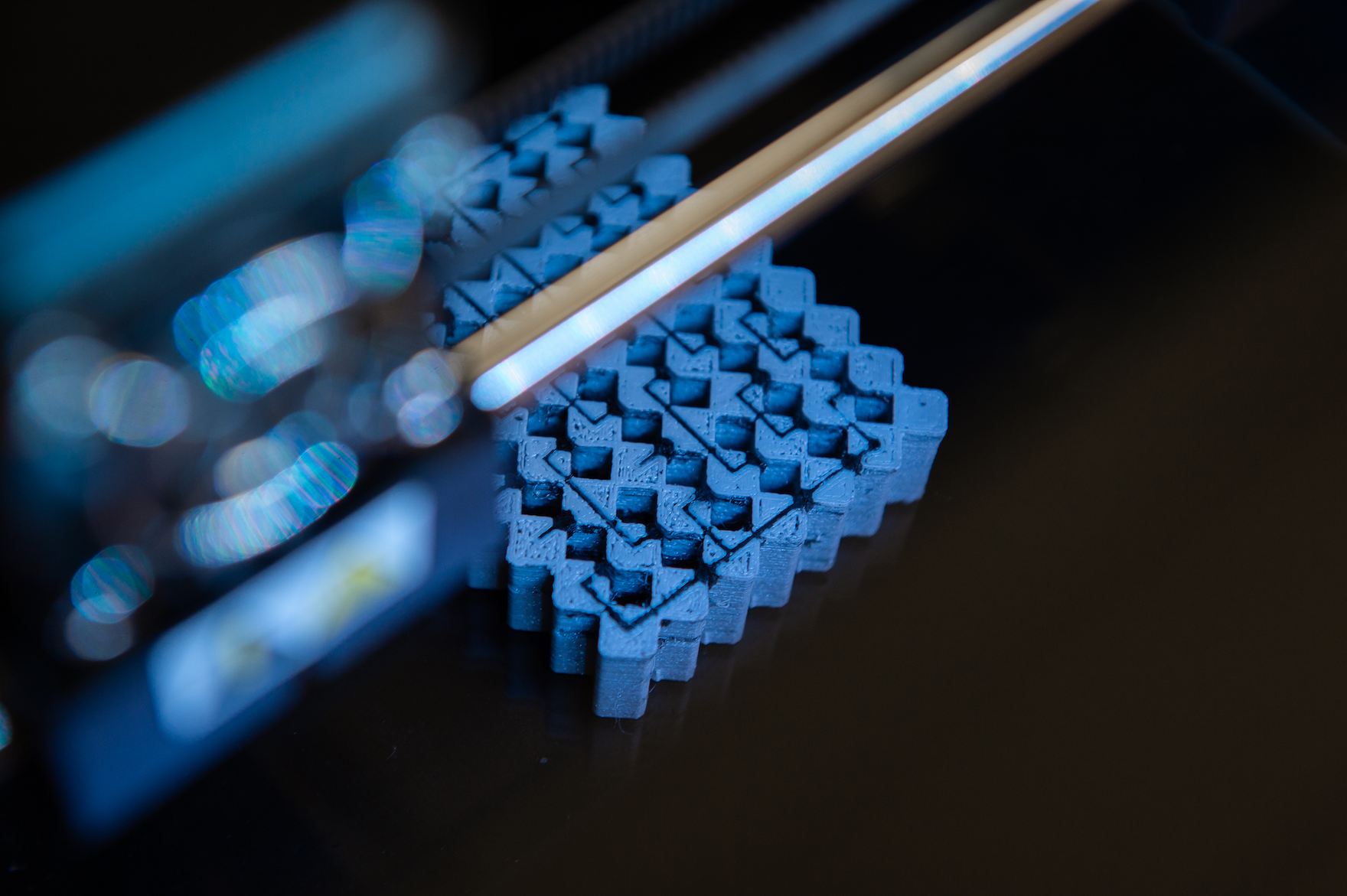

True technological revolutions — such as the invention of the steam engine or electrification — are very rare. They have unparalleled power to spur entirely new sectors of the economy. Debate continues about the impacts of digitization on productivity. But there is no denying that new technologies combining digital, physical and biological realms — data science, robotics, biotechnology — are creating a whole new economy.

What are the options for the path ahead? Global institutions are notoriously difficult to reform, let alone create. But historically, times of crisis are their incubator.

The revolutionary nature of the change is most obvious in the applications of artificial intelligence (AI) to help solve basic data problems such as predicting protein folding, assisting medical imaging, fighting cyberattacks, and creating autonomous robotics and virtual reality simulations and games.

In concrete terms, these new technologies create virtually limitless streams of new data. Estimates of the amount of data generated, captured, copied and consumed around the globe are mind-blowing. In 2010, the volume of global data was about two zettabytes (two trillion gigabytes). It is expected to reach 120 zettabytes in 2023.

Swelling data flows create significant opportunities for governments to improve and adjust services, analysis and communications. Similarly, new data enables companies to innovate and offer new products for consumers. But with those opportunities come new risks, such as higher stakes for consumer data protection and privacy. Many governments around the world are passing or urgently developing legislation to try to manage data within their borders. But a path forward for international norms or standards is not clear.

It’s obvious that data governance will be essential to international cooperation in the near term, given the burgeoning role of data in the global economy. At the same time, further fragmentation of the existing order risks entrenching digital realms around the world into isolated or shielded blocs. In such a scenario, one can easily envision even less international cohesion and more rivalry. There is a growing risk of an international digital and data-driven arms race becoming the new normal. AI currently looks like a race with few rules.

Common human problems — led by climate change and inequality — require shared solutions. And global institutions urgently need fresh tools and approaches with which to tackle change and re-energize international cooperation. Digital and data governance, given its exponential ascent in relevance for all countries, is a potential theme and vehicle for driving broader reform and change. Canada can lead in proposing ways forward.

What are the options for the path ahead? Global institutions are notoriously difficult to reform, let alone create. But historically, times of crisis are their incubator. It may be that the current state of international affairs is disruptive enough to create the conditions necessary for a significant adjustment in the international system.

There are many historical precedents, but rarely smooth ones. For example, the global financial system we now have arose out of the ashes of global conflict. The Group of Twenty Leaders’ Summit in 2008 was a response to a global recession. The International Energy Agency was created in 1974, following major conflict in the Middle East and the oil crisis of 1973.

The Centre for International Governance Innovation has proposed the development of an international digital body, a Digital Stability Board, with a view to building an effective international system of data governance. It follows the example of the Financial Stability Board created in the aftermath of the 2008 global financial crisis.

No concrete model for a digital body has yet emerged. But initiatives are under way that could serve as a starting point. This includes the Digital Economy Partnership Agreement, a plurilateral trade framework seeking to build cooperation on a range of emerging digital economy issues, including AI, digital identities and digital inclusion.

Over the past century and a half, Canada has positioned itself to become a strong natural resources and trading power within a rules-based global market. More recently, this country has taken steps to be in the vanguard of innovation in AI and quantum computing. It’s essential that this position now be leveraged to good advantage. Canada can help design digital and data governance models to build a new level of cooperation through global institutions. The time to do this is now.

A version of this piece is cross-published with iPolitics.ca.